The Electronic Intifada Dallas 28 July 2011

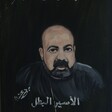

The author’s grandmother holding a photo taken in 2006, the last time she was able to visit her son.

It’s been six months since I was in Gaza and I miss everything about it. I miss the company of my large extended family, the delicious food we enjoyed from communal trays as we sat on the ground, the gorgeous sunsets on the beach and the peace of mind and serenity that only come with the feeling of being home. I think about the kind but tortured people I met and the impossible-to-forget harshness of life in Gaza. But out of all of the inmates of this outdoor prison, there is one in particular that cannot escape my thoughts.

Although all of Gaza’s 1.6 million residents feel suffocated by siege and closure, there are nearly 700 Gazans who have it immeasurably worse. They are the Gazans being held illegally in Israeli prisons. During my two months in Gaza, I heard about a prisoner from Bureij refugee camp who had been released after being imprisoned for more than a decade. His family rejoiced upon his return, welcomed him back with what was described to me as a parade, and married him to a beautiful young bride to celebrate his freedom and assist him in finally beginning his life. Everyone in my family was thrilled to share this story, and although no one said it, all we could think about was the day we’d finally be able to celebrate like the family from Bureij when my incarcerated uncle is freed.

During the first intifada, my uncle was a college student majoring in chemistry. It was common for Israeli soldiers during this period to arbitrarily arrest young Palestinian men and then compile a list of charges to pin against them using the testimonies of other tortured inmates. Like most of Palestine’s young men, my uncle was detained without being charged, and a few days before his scheduled release, two severely tortured men told similar stories to Israeli authorities that implicated my uncle in what Israel would define as criminal acts. Quickly after this, my uncle was sentenced to several consecutive life sentences without a fair trial or legitimate evidence against him.

He has been in prison for more than twenty years now, but I’m told that I knew him when I was a toddler. I am also told that I visited him in prison a number of times as a young child. I don’t remember ever meeting him, but that doesn’t change how much I miss him. It has been nearly five years since anyone from our family has seen him. In the past, my grandmother would travel twenty hours to visit him every week. Then things grew more difficult; my grandmother’s health worsened and security at the border tightened, causing visits to be terminated for extended periods of time. After Hamas’ electoral victory in Gaza in 2006, visits became nearly impossible. In June of 2007, when Hamas assumed control of Gaza and Israel sharpened its policy of collective punishment against Gaza’s population, the visits were completely banned. In December of 2009, the Israeli high court upheld this inhumane practice, preventing Palestinians in Gaza from visiting their imprisoned relatives across the boundary with Israel.

At present, the only communication we have with my uncle is through cell phones smuggled into the prison and hidden by the prisoners. My grandmother speaks to him frequently, but their conversations are short and fragmented. This contraband cell phone is our only link to him but we know that if it is found by the Israeli guards, he will be severely punished. This, in fact, happened at my uncle’s prison while I was in Gaza last winter. Prison guards found a cell phone hidden inside the wall of a prison cell and began a cell-by-cell search to discover any more hidden communication devices.

They searched the walls, ripped open pillows and mattresses and rummaged through the prisoners’ belongings. As this took place, each prisoner was held back by four guards and even after their cells were searched they were chaperoned minute by minute, day and night in their cells. We didn’t hear from my uncle for more than a week and everyone grew very worried, expecting the worst. Not only do the relatives of the imprisoned have to deal with the anguish of being apart from their loved ones, they have to worry about torture and abuse — “accidents” like the one that took the life of Mohammad al-Ashqar in 2007 when he was brutally shot during a drill aimed at boosting the morale of the Israeli prison guards. Palestinian prisoners endure a lack of treatment for health problems and illness, inadequate clothing and linens (especially in the winter) and poor quality and limited amounts of food.

While I was in Gaza, I spoke to my uncle three times on the phone. Although it wasn’t the ideal way for an uncle and niece to meet and get acquainted with one another, we were grateful for the opportunity. I told him about my life and goals, gave him short biographies on my siblings in the US and told him about all of the things I’d seen and learned in Gaza. Although all of our conversations together totalled less than one hour, these were some of the most meaningful moments I spent in Gaza. He didn’t complain to me about his terrible fate or the prison guards and the terrible food; he told me about how lucky he was and how others have it so much worse.

Now that I am on the other side of the world and my uncle’s cell phone can’t reach me, I crave his wisdom and insight. There is a remarkable calmness in the souls of imprisoned Palestinians. Maybe because for years they have breathed the ancient and poetic winds of the Naqab (Negev) desert. Maybe it’s the countless hours they dedicate daily to contemplation and reflection on life. Maybe it’s the sense of patience they have been forced to develop. Or maybe it’s their well-tested faith. But there is something that distinguishes the Palestinian prisoner from any other person in the world. They are the living martyrs. Their immortalized faces aren’t postered on the alleys of refugee camps and their names aren’t sung in intifada anthems. They are not memorialized but their sacrifice is just as great.

Fidaa Elaydi is a Palestinian boycott, divestment and sanctions activist and law student. She recently traveled to Gaza and completed a internship with a Palestinian nongovernmental organization. As a third generation refugee, she strongly believes in the right of return and plans to soon fulfill this right.