The Electronic Intifada 23 December 2011

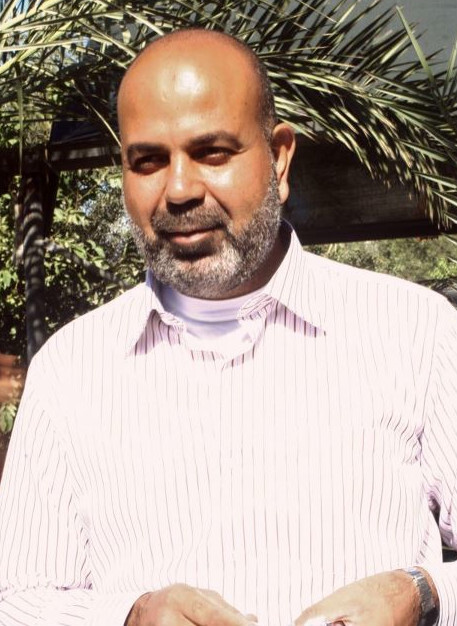

The author’s uncle, shortly after his release from Israeli prison in October.

The Electronic IntifadaFive months ago, I wrote an essay for The EIectronic Intifada about the uniquely Palestinian way I was able to get to know my uncle.

Our story is not uncommon because nearly every Palestinian family has been touched by Israel’s arrests without charge, unfair trials, severe torture, and illegal transfer to prisons outside of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

When I was in Gaza one year ago, I was able to reconnect with my relatives, but my uncle Hazem, a political prisoner at the time, was not among them. He was in Nafha prison, serving several consecutive life sentences after an unfair trial that relied entirely on hearsay evidence more than twenty years ago.

I was able to speak to my uncle over the phone several times while I was in Gaza. Unsurprisingly, these were not calls the Israeli authorities allowed my uncle to make, as prisoners are not permitted to make phone calls of any kind. Using contraband cell phones that the prisoners found access to and hid discreetly in their cells, my uncle called us regularly.

As a Palestinian born and raised outside of Palestine’s borders, my experience with the Israeli occupation has not been as thorough and traumatic as that of my counterparts born in Palestine. I have always heard Israel’s military forces described in super-human terms: they hear and see everything that you say and do, they’re merciless and indiscriminate, they have weapons that can find you wherever you are, they know what you will eat for dinner before you have decided, and so on.

I have never accepted these characterizations because I always saw them as a symbol of the defeatist attitude many Palestinians have, and I saw them as a way of submitting to the injustices we as a people are forced to endure. I refused to see Israel as omnipotent and omnipresent. True, Israel has a well-equipped and well-trained army of brainwashed, bigoted and self-serving individuals, but its ideology is one that can be defeated by brave individuals willing to stand up for truth, equality and international law.

Underestimating Israeli brutality

After my essay was published, I learned that my lack of suffering under occupation made me severely underestimate the truth of the characterizations given to Israel. I learned how far and how deep the tentacles of Israeli intelligence reach.

Shortly after the article was published, the Israeli authorities barged into my uncle’s cell with a copy of the essay translated into Arabic and a line under the part mentioning the contraband cell phone. The guards asked my uncle what the essay was referring to, and if there was truth to these claims. My uncle’s name was not mentioned in the article — nor was the name of the prison, his charges or any other details about him.

My uncle was removed from his cell, he was subjected to harsh and severe physical punishment, and shortly thereafter was transferred to a different prison. The orders to take these actions against my uncle seemingly did not come from the authorities at the prison — rather, these were orders from high-ranking officials within the Israeli intelligence bureaucracy.

Learning of these consequences to the article I wrote taught me a great lesson: being far from occupation means I do not understand it. No one can fully understand the struggles and strife that Palestinians endure without personal experience — and this experience cannot be gained vicariously through others or through research and scholarship. I severely underestimated the tightness of the grasp Israel has on Palestinians and all forms of their resistance, whether it be protesting, stone-throwing, boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) activism, or any other form of speaking out against their inhumane, unjust and illegal policies.

If you are wondering why I am again writing an essay and why I have not learned my lesson from the terrible fate my uncle was forced to face as a consequence of my last one, then allow me to explain. I am a firm believer that the right action is rewarded. And although my attempt at sharing with the world the pain that comes with being separated from a loved one led to further pain, it also paved the way for a bright and far more hopeful future.

Three weeks after my uncle was transferred to a different prison as punishment for the essay I wrote, news surfaced of a possible prisoner exchange deal between Hamas and Israel. As soon as I stumbled upon this information, my eyes welled up with tears and I began searching endlessly for a list of the names of the prisoners to be exchanged. I was unable to find any details online and I began to search through my contacts. I asked relatives, friends, activists and everyone else I knew in Palestine if a list had been published and if I could gain access to it. As I nervously and excitedly worked to find if we would be among the families blessed with the homecoming of a beloved and long-estranged hero, I tried to keep my hopefulness in check so that I would not soon be crushingly disappointed. This was a fruitless effort.

Our piece of the struggle

Throughout my entire life, my uncle Hazem has been our connection to the Palestinian struggle. Every Palestinian family has a tie — some have martyrs, some have loved ones who have been severely disabled by Israeli missiles or bullets, some have demolished homes, others have lost opportunities, or relatives in a fragmented family forced to live in the different corners of the world. My uncle Hazem was our tie; he was what made the occupation part of our every waking moment.

Sometimes, you can forget about the bleakness of life in a refugee camp and the budgeting of your monthly salary to make sure your kids have food to eat until the next paycheck and, all of a sudden, occupation doesn’t seem out of the ordinary. But my uncle Hazem’s absence was never forgotten — and the pain of being separate from him has never receded. In my mind, I linked his freedom with the freedom of Palestine in its entirety, with our return to our hometowns, with the prosperity of my people, and prayers in al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. It was all one struggle, and every act of resistance was to serve all of these goals. I always hoped he’d be released but in all honesty never believed the day would come. During these few uncertain days his freedom seemed like it was on the horizon.

I remember the moment I was told he’d be among those released. I was sitting in the back corner of the law library reading about privity of estate for my property law class. I had no idea what I was reading and was so distracted by thoughts of the prisoner exchange that I decided to check my Facebook account for any updates from relatives about the status of my uncle.

I read a message from a relative that my uncle Hazem was number 40 on the list. I froze. I felt like I was in shock, like the world had stood still, and I reread the sentence several times before I was able to comprehend the meaning of the words I was reading.

The exchange was set to take place in one week. Seven days from that moment, my uncle would be in the warm embrace of his frail and ailing mother; he’d be among his brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews; he’d be walking around Gaza in civilian clothing breathing free air, unshackled, and under no one’s supervision. I realized tears were streaming down my face and again I feared I had lost the reins to my hopes and that they were far beyond my control.

I decided I’d wait for an officially-published document before I’d let these thoughts enter my mind again. Soon after, I saw pictures of a handwritten document listing the names of the prisoners — and on that paper, my uncle was listed number 40. I was afraid of the disappointment that might follow if I accepted this as truth. I waited still. Then the list was published by a Palestinian news source. This was the moment I decided to believe in his possible freedom; it was real. My uncle’s freedom was no longer part of a distant dream in which I warned myself not to get caught up — it was reality. And soon he’d be among us — well, at least among my other relatives in Gaza.

I rejoiced. I began planning when I would call to speak to him, I asked relatives to take pictures and videos of the festivities that would take place to welcome him home, I decided I’d pass sweets around to my law school class, I would arrange a time for my uncle and I to meet face-to-face via Skype. His release became the center of my life and I struggled to rip my mind from it in order to study or sleep or eat.

I spoke to my relatives in Gaza on a daily basis, and their plans to welcome him were elaborate: all of my aunts and uncles all over the Arab world and the West would travel to Gaza immediately to welcome him (they had not all gathered in one city for over three decades). They would have a party with dancing, singing and ululations upstairs for the women, there would be a feast downstairs under a massive tent for the men, and all of our extended relatives by marriage and blood — both closely and distant related — and neighbors and community leaders would join to share in our celebration.

Overjoyed

Before my uncle was even released, the hunt to find him the perfect bride began. We were all so overjoyed. Many of my cousins, like me, were babies or toddlers when my uncle was imprisoned and we don’t remember him before his imprisonment, but he has always held a special place in our hearts. I can confidently say the day of his release was the happiest day of my existence and I cannot imagine any day that can overshadow the sheer bliss that filled my heart on that special day.

Although I had a deadline for major assignment on 18 October — the day of the exchange — I stayed up all night nervously watching our satellite feed of Al Jazeera, hoping and praying that nothing would go wrong, and making brownies for my class. It is an old Arab custom to pass out sweets on special occasions and, although I could not celebrate in Katiba Square with my compatriots or in Deir al-Balah refugee camp with my family, I was set on finding a way to celebrate this monumental day.

As I watched the buses cross into the Gaza Strip at Rafah, I lost all control. I was not just crying, I was sobbing. My emotional reaction was hard for me to understand — it was a combination of ecstasy, total disbelief and shock, and utter sorrow. I was thrilled because I have been dreaming of this day since I was old enough to understand my uncle’s absence. I was shrouded in disbelief and shock because, in my adult life, there have been very few Palestinian victories and this was too great a success for me to fathom. And my sorrow, of course was founded in selfishness: I wanted to celebrate with my family, I wanted to welcome my uncle home with a bear hug and a pathetic attempt at a traditional Palestinian ululation; I wanted to be part of this historic homecoming.

As Egyptian reporters interviewed the prisoners on the buses, I searched anxiously for my uncle. “Maybe if I see him on one of these buses, this will stop feeling so surreal and I’ll know, finally, that he is safe,” I thought.

I didn’t see him on Al Jazeera, but after ninety people ate my brownies and I got through my lectures with the vigor and energy of a zombie, I rushed home to speak with my uncle. It was then that he told me of the horror he faced after my last essay, but he spent the majority of the call reminding me that our struggle has not yet ended. He told me of his beloved friends who were still unjustly behind bars, how many of them suffered severe psychological problems as a result of the conditions in the prisons and how some have even gone completely insane. He told me about men who have gone blind or have weakened health as a result of poor or non-existent medical treatment for treatable and preventable illnesses. He told me that we cannot forget about our brothers and sisters still suffering behind bars, and he said that none of us will be free until all of them are released.

His freedom was bittersweet, he told me. Although he was thrilled to be among his family and surrounded by loved ones, he could not forget about his comrades who were not as lucky as he was to be among those released.

My uncle did not complain to me about how tasteless the prison food was, the pain of torture, or the suffocation of imprisonment. It has never been the way of Palestinians to complain. We have never sought the pity of others. We simply seek to share our stories in order to gain support for our struggle and understanding of our cause. My uncle did not want me to feel sorry for him or regret speaking out against illegal imprisonment — he wanted me to see that even when things seem hopeless and unbearable, there is unimaginable beauty and peace ahead, and that the pain we experience should only strengthen our resolve so that we are better suited for the pleasure ahead.

His message is a universal one, and one that Palestinians have lived by for generations: our fight is not easy and it requires sacrifice, but if we were not suited for it, then it would have been assigned to another people. We must resist until we are free.

It has been two months since my uncle’s release. Since then, he has fulfilled his religious obligation of Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), he has married, and my aunts and uncles in the diaspora have returned to their adopted homelands. As he grows more and more accustomed to his new life and freedom, I grow more and more excited to meet him.

Not many young women have the pleasure of meeting their lifetime heroes, but I am among the lucky few. Tonight I packed my bags, and tomorrow I begin my two-day journey to Gaza to meet by beloved uncle. Our reunion has been long delayed but the anticipation seems to only increase.

Fidaa Elaydi is a Palestinian boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) activist and law student. She is visiting Gaza to meet her uncle, a political prisoner who was released in the October 2011 prisoner exchange deal between Israel and Hamas. She is a third-generation refugee who strongly believes in the right of return.