The Electronic Intifada 24 September 2014

This small volume of poetry by Ruth Padel — a well-established British poet whose eclectic works have covered subjects as diverse as Walter Ralegh, tiger conservation and Greek tragedy — is an example of the kind of issues that will likely crop up.

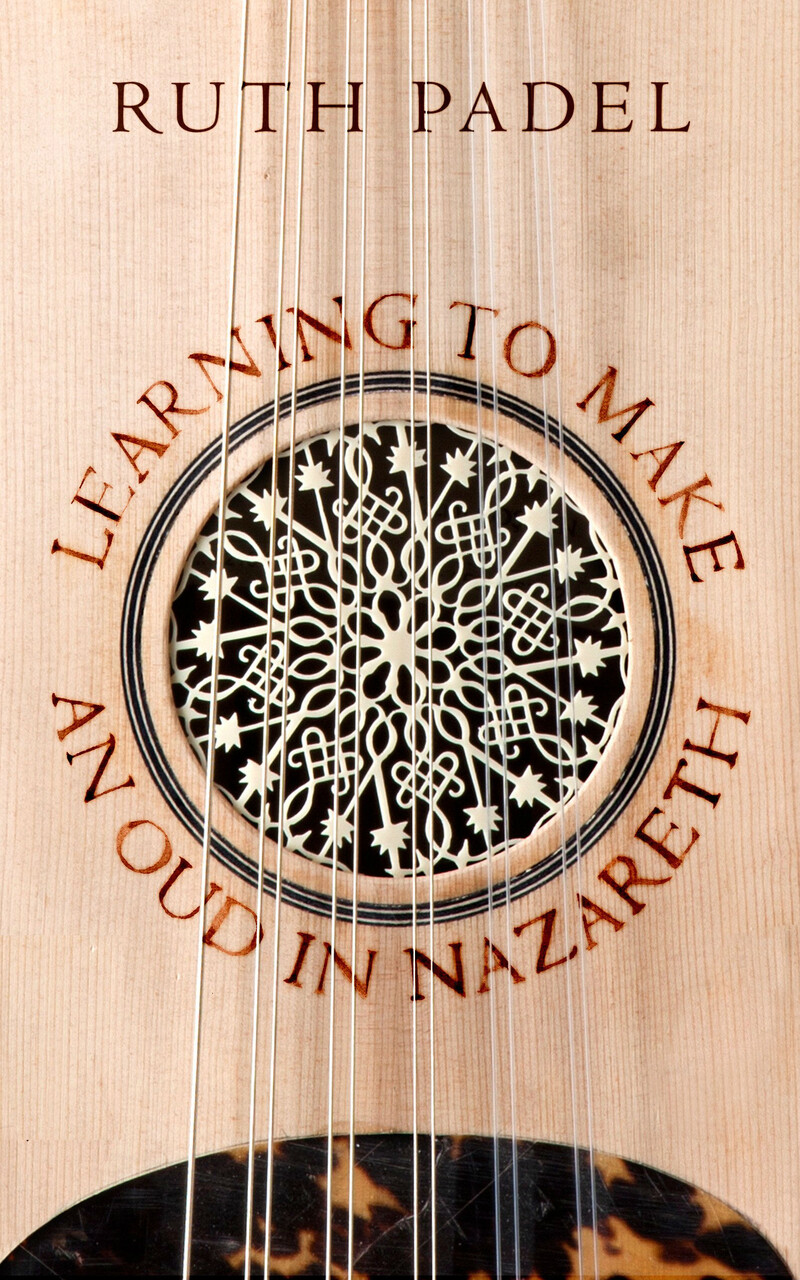

Not every poem in the collection, titled Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth, engages with the question of Palestine per se. But the majority do in one way or another, and often in ways that are inventive and resonant.

Padel teaches creative writing at the University of London, is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a multi-award-winning writer, so, as one might expect, there is some fine poetry in this book.

Moving

The title poem, for example, is a beautiful, moving piece. It weaves together the process of lovingly shaping an oud — the Arabic musical instrument which is the ancestor of the European lute and, ultimately, the guitar — with a commentary on Israeli racism, and with Biblical references. The rich, evocative description of the craftsman’s work:

He damascened a rose of horn

with arabesques

as lustrous as under-leaves of olive beside the sea

evokes a physicality which blends with descriptions of the lovers drawn from the Old Testament:

His left hand

shall be under my head

… He shall lie all night between my breasts

This is then juxtaposed with the threat which occupation and racism pose to both love and art:

On the sixth day the soldiers came

for his genetic code.

We have no record of what happened.

combined with the frenzied fear of the lover from the “Song of Solomon”:

I sought him and found him not

I called but he gave me no answer.

Erudition

Padel’s characteristic erudition is on display in other poems which tackle the politics of Palestine.

“Paint us, they said, the world as it is. No more / of your children’s games and peasant weddings,” unnamed voices demand of the artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in “Pieter the Funny One.”

From those innocent beginnings the voices — of conscience? of the world? — pursue the painter (in a fictionalized, turned-about chronology), forcing him instead to depict “a totally annihilated village” within which is buried:

… Forty disabled kids

with their mothers. And a Beirut reporter.

That’s more like it, they said. We want

the world we live in …

Intention

One of the themes which recurs through many of the poems is the representation of Palestine in Western culture. At a reading at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, Padel noted that she hadn’t visited Palestine in fifteen years, so that many of the scenes she evokes come from her memories, imagination or — in the case of “Capoeira Boy” — a video on YouTube.

This has some side-effects which are worthy of comment. This book is, of course, one of poetry, of artistic production, with no claim to “represent” Palestine or its people’s struggle, or to depict them accurately. But it can jar when, for instance, the lines of “Capoeira Boy” place the occupied West Bank city of Hebron and the refugee camp of Jalazone (north of Ramallah) together, as if the writer thinks that they are geographically adjacent.

If poems are intended to make us feel something about a subject, to be moved or inspired, does the artist producing them have some kind of responsibility in the way that he or she portrays that subject?

It is entirely legitimate for a Western writer to engage with the many ways in which Western culture has thought about and been affected by Palestine and its history — most directly, of course, through the three great monotheistic faiths and the significance in which they hold this small piece of land. But it also behoves the writer to tackle the subject with care.

Thought-provoking

In many ways, Padel’s book is not “about” Palestine; it is “about” the many things that Palestine means to Western culture — gorgeously erotic Biblical poetry, or horrific scenes on the news, or the religious themes of early Renaissance paintings, or our witnessing of “cultural resistance” in a refugee camp many miles and time zones away, via a computer screen.

And it is this perspective, one senses, that makes it ethically right for Padel’s book to also contain a poem (“The Chain”) about a Jewish concentration camp inmate (who was ultimately killed in Auschwitz) carving an intricate and beautiful gift for his wife. And another about the brutal eradication of the Jews of Crete by the Nazis.

The Holocaust and the extermination of Europe’s Jews usually appear in juxtaposition to the issue of Palestine either in clumsy attempts to equate the two, or in even more clumsy attempts to paint supporters of Palestinian liberation as anti-Semites.

But in Padel’s hands the two issues do belong together, because the overriding theme of this book, summed up in the final line of the final poem, is that “Making is our defense against the dark.” That “making” might be a child’s fighting-dancing in Jalazone, or the physical creativity of eroticism, or the music of the first and last poems in the book.

The painter, the oud-maker, the musician, the wood-carver in the Nazi death camp and the ordinary person who defies the daily checkpoints to continue making love and art are all arrayed together against “the dark” — which, according to situation, might be the silence of a musician’s broken hands or “air attacks on Gaza.”

Ruth Padel’s poems might have little to say about the reality of modern Palestine, but they are eloquent and thought-provoking on the West’s ancient spiritual, aesthetic, colonial relationship with the Middle East, and our deeply problematic moral entanglement with the “Holy Land.”

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this review referred to the eradication of the Jews of Cyprus by the Nazis when it should have referred to Crete. It has since been corrected.

Sarah Irving is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone, a collection of contemporary Palestinian poetry in translation. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh.

Comments

it is a disgrace to compare

Permalink Anonymous replied on

it is a disgrace to compare Gaza to Auschwitz. No one will take this seriously; the only appropriate reaction is the one I offered in my first sentence.

A subtle point

Permalink mary replied on

Actually, anonymous, the reviewer makes clear that there is no direct comparison in this book. She says, "The Holocaust and the extermination of Europe’s Jews usually appear in juxtaposition to the issue of Palestine either in clumsy attempts to equate the two, or in even more clumsy attempts to paint supporters of Palestinian liberation as anti-Semites." She then says that is not the case in this book. Where the two struggles against genocidal actions are equated are in acts of creation. It sounds to me as if these poems celebrate the humanity and creativity of both Palestinians and Jews, and that makes me want to read the book.

Hmm, I see. So when word

Permalink Boaz replied on

Hmm, I see. So when word-association is employed to illicit a sentimental reaction, it is the audience and not the author who is responsible for being misled?

Perhaps a better understanding of such terminology (eg: Holocaust, genocide, Auschwitz, fascism, Israel, Zionism, etc...) is required before those on the so-called "progressive-left" use them in their literature.