Tall tapered trees, characteristic of the northern West Bank landscape, tower over the valleys of Nablus (Issa Mikel)

“In the prison of his days, teach the free man how to praise” — W. H. Auden

Some of the first images greeting me upon setting out from Abu Dis to Nablus are the skeletal Bedouin shanties dotting the stony hills on either side of the highway and the Bedouin children scampering along in their rags near the roadside. Merely dusty apparitions in the distance to the majority of those who travel the roads of Palestine, they generally go unnoticed to the self-designated civilized populace of the country, Israeli and Palestinian alike. Once before, while on the highway to the Dead Sea, I noticed an ambulance and a car stopped at the roadside near a shanty village. As I rode past, I glimpsed the bottoms of two dirty little bare feet peeking out from underneath a pack of crouching medical technicians.

Today I am heading for Nablus, a city in the north of the West Bank, renowned for its rich history, economic vibrancy, and political independence and non-conformism. A journalist friend and his colleague who will be filming in Nablus invited me along for the trip and I agreed.

The farther away from Abu Dis I get, the more barren the landscape becomes. About half way to the Qalandia checkpoint, the main clot in the artery between Jerusalem and Ramallah, an Israeli military installation of some sort crops out of the mountain. Consisting mostly of metal fencing and small armored personnel carriers, it is no doubt not a major military base, only one of the hundreds of nodes in the Israeli military complex that stretches across the West Bank and Gaza in a giant colonial archipelago. But most imposing of all is not the armor, but what is hidden from the eye. As high as a house, half a dozen grey shapes flap in the wind: giant bulldozers covered from top to bottom in drab tarpaulin rising against the sky. Though completely hidden from sight, their outlines are unmistakable, projecting an even more ghoulish sight than if they were in full view. I cannot guess the exact nature of their last mission, but in any case one cannot help but shudder.

Eventually I reach the monstrous confluence of people, automobiles, trash, and concrete that is Qalandia checkpoint, which severs the northern districts from the rest of the West Bank. The cattle pen of Qalandia is being turned into a permanent international border (though it is far from the Green Line, eight kilometers inside the West Bank), and in preparation thereof, bulldozers and Palestinian laborers are building immaculate new cattle pens with rosy patterns on the walls and what appear to be interrogation rooms. What with the guns, the wall, and the aroma of garbage and kebabs, few checkpoints offer a more sanguine view of benevolent colonialism than Qalandia.

Surrounded by towers of drying soap, a laborer expertly hand-wraps individual bars of pure olive oil soap in a Nablus factory (Issa Mikel)

My passage through the checkpoint is achieved with relative ease, for it is always easier to travel outward from the Israeli center than inward. I intentionally neglect to speak of passing out of or into Israel proper, for the occupation has made the notion of official borders over one defined geographic area an anachronism. It is more useful to think of the Israeli penumbra of control in terms of various grades and centers of inclusion and exclusion.

On the one hand is the Israeli center, comprising the Green Line and the ring of colonial settlement areas ringing Jerusalem. And on the other are the islands of colonial settler outposts littering the rest of the country and forming miniature Israeli centers, as well as the various annexed territories nibbled away from the edges of the West Bank and Gaza over the years (such as with the current wall). Everything else is the dark outside wherein the “Nazi Arab hordes” reside and where one is told that a Jew will be “torn to shreds” upon entry (two quotes I recently read on internet chats). If you are Palestinian, getting out of the centers is easy; getting in difficult or impossible. Thus, though the analogies of the prison and the Bantustan are often used, they are spot on descriptions of political and military reality.

Shortly after I reach Ramallah, my friend and I make for Nablus, which sits nestled between two ranges of hills. The city’s nickname is the “Mountain of Fire,” for the way in which its inhabitants once repelled foreign invaders by setting fires along the mountainside. To this day it sits in an uneasy political relationship with the central “government” in Ramallah. On the rode north the stony landscape greens and one loses oneself in the beauty of the trees and hills. For a few brief moments one can almost forget the war, the wall, and the rest of it.

Then one reaches the two major checkpoints at the mouth of the valley in which Nablus sits. Once a lively city, the Nablus of today is the victim both of geography and racist geopolitics. With its back to the range of hills and few channels of intercourse with the rest of the country, the Israeli military has had little difficulty in isolating the town. A series of checkpoints choke Nablus economically and culturally, stifling what has traditionally been one of Palestine’s most important urban centers. As one of the centers of resistance, both violent and nonviolent, as well as a bastion of Islamist support in the West Bank, Nablus has earned pride of place near the top of the Israeli government’s hit list and has been targeted with great resentment and vitriol.

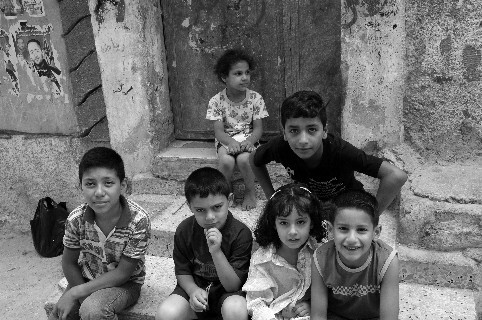

In overcrowded Balata camp, children pour out into the streets (Issa Mikel)

Not alone among Palestinian cities, it has also fallen victim to the gang factionalism and personal politics of the Palestinian Authority and various thuggish satellite factions like the Al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigade and Tanzim. In a scene representative of the Chicago-like state of affairs, the story has it that the brother of the city’s former mayor (who was originally appointed by Yasir Arafat) was assassinated by Al-Aqsa.

However, Nablus captured our hearts. The finest part of our stay was our host, Khaled, whom my companions had met on their previous visit to Nablus. An intelligent, well-read man with a wry wit and somewhat churlish mannerisms, not far beneath the surface Khaled is a kind and generous person. And though he likes to goad people with a grouchy sense of humor and stark statements of political opinion, underneath he is a thoughtful person and a sharp mind. He is also deeply committed politically and tries his best to live his beliefs, though the years of struggle and heartache have left their mark.

Khaled’s grandfather was one of the largest landowners in Palestine and during the British Mandate was offered a great sum of money by the Jewish National Fund for his land. Though he desperately needed the money, his grandfather sold the land to the Latin Church for much less than the JNF had offered. He thought that it was more important to pass along knowledge to one’s children than money. With the smile of a school prankster, Khaled joked, “I would rather have gotten the money.”

Khaled, his wife, and a circle of friends have attempted for years to lead a peaceful civil resistance to the Israeli occupation. A number of years ago they began a boycott of Israeli and American goods, no small feat considering the overwhelming occupation of shelf space that Israeli goods have attained in the stores of Gaza and the West Bank. (According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics,some 85 percent of the Occupied Territories’ imports come from Israel.) One of the facets of Israel’s system of closure is to impede the movement of Palestinian goods while allowing the dumping of its own goods into the Palestinian market. In one supermarket in Nablus, we struggled to find Palestinian-made hummus among the array of Israeli varieties. Whenever store employees encourage Khaled’s wife to buy a particular item because it is Israeli, touting its quality, she simply tells them, “let them keep shitting on you.”

Despite it all, these boys in Balata camp are all smiles (Issa Mikel)

But with the current situation, such collective action is difficult to maintain and the boycott has lost momentum. People are tired and it is difficult to convince others the value of a boycott, not to mention the greater economic forces at work - like the steady deindustrialization of the Palestinian economy at the hands of the occupation machine. Though he maintains his commitment, sadness and fatigue are apparent in Khaled’s face and tone of voice. “Sometimes I just get tired. Other times I wonder whether I’m just a fool.”

Aside from their larger political aims, it occurred to me that such acts express a basic desire to exert some shred of control over one’s life in a world gone mad. Though staunch supporters of the Israeli racist regime no doubt will find a way of painting such efforts as acts of aggression, though cynics will criticize such boycotts as unrealistic, one detects a need just to stand up and say “no” to the total colonialism of the occupation. Everywhere one goes in Palestine, from supermarkets to checkpoints, one feels as though overcome by a great tidal wave of economic, political, and military occupation that leaves few areas of life untouched. Occupation hangs heavy in the air and imprints itself upon people’s thoughts and behavior. Little wonder it means so much to so many that they not be squelched without raising some cry of protest.

Indeed, throughout our visit in Nablus, we repeatedly heard the calls of frustration and expressions of impotence. As we filmed on the streets of the city center, a man named Salah marched up to us in a huff to ask us who we were before rattling off a list of frustrations, from the taking of his identity documents by the Israeli soldiers at the Huwwara checkpoint to his inability to find regular employment. We stood limply, feeling silly and totally ineffectual while he asked us heatedly what we were going to do to help him, how a film would have any effect on Israel. Once again in the Balata refugee camp, the refugee children suffer the effects of poverty and war trauma, waking up nights screaming from their nightmares. Again and again, people were eager to tell us of their profound feelings of injustice, that they were being wronged again and again and that no one was listening.

One need merely walk around Nablus or any other Palestinian town or village to witness how people attempt to take back their lives, whether peacefully or violently, and struggle within a larger system of poverty, politics, and violence. But it would be a mistake to see Palestine’s problems as unique. From labor activists in sweatshops to farmers who are trying to resist economic domination by large agri-business companies like Monsato, the connection that many find so elusive strikes me as obvious. All of them are calling out for some control over their lives and determined that they should matter - determined that their concerns, their jobs, their families, and all the detritus of their lives should matter. Not that they wish their lives to matter in a cosmic sense or even that they matter to others as such (though some no doubt do as well). Their desire is even more basic: that their own lives be allowed to matter to them, that they be allowed to simply carry on.

These are desires so basic and universal, yet the grand average of the American populace fail to see them. Even in the most sympathetic of foreign eyes the concerns of Palestinians warp into quaint cultural sensitivities. At best, we feel aggrieved because “our women” have been searched and our honor molested. At worst, we are animated by anti-Semitic hatred and a violent culture. Human conceptions of fellow humans are perhaps everywhere poverty stricken. It appears all too easy to forget the complexity and importance of our own profane little lives.

With our blue American passports, we leave Nablus with little difficulty other than the usual checkpoint queues. On my way back to Abu Dis, the landscape returns from green to stony grey and the Bedouin shanties once again go unnoticed.

Related links:

Issa Mikel is a Palestinian-American lawyer currently freelance writing and engaging in non-profit work in Palestine