The Electronic Intifada 8 August 2005

Nablus at sunset. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

“It was a very big house, but nothing of it exists except this story,” says architect Naseer Arafat of his family’s house that was destroyed by the British forces during their rule in Palestine in the early 20th century.

The story goes that 50 family members were living in the house, including one who happened to be a revolutionary, fighting for independence from the British — this was before the establishment of the state of Israel and its later occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. When the British came to the house to arrest the freedom fighter (the rest of the men had fled, while this man was wounded), the women of the family dressed him in the full chador worn at the time, which obscured the entire body and face, and attempted to pass their wanted kin as an ailing old woman.

A building near the outskirts of Nablus. (Zachary Wales)

Naseer Arafat had never seen the house, but as a boy he walked over its ruins every day on his way to school, and says his family “kept remembering the sadness of that day.”

It is no wonder, given the significance of this story in Arafat’s childhood, that he would dedicate his life to breathing new life into old and decaying buildings, and to protect the historical legacy of Nablus’ ancient buildings.

His current project, “a ten year dream,” as he calls it, is the restoration of an estate that was once owned by an influential sheikh and housed a residence, soap factory and reception hall. Two of the sheikh’s descendents live in the house and donated a large portion of it to be refurbished into a cultural center. They are also helping to pay for the project, which is not being sponsored by major donor agencies, unlike so much of the development work in the occupied Palestinian territories.

A work in progress: The upstairs portion of the compound.

(Zachary Wales)

The compound, which Arafat describes as having a “unique composition,” is nestled in Nablus’ Old City, home to 20,000 Palestinians and some 2,560 historic buildings, mostly constructed during the Ottoman period, as well as some from the Mameluke, Crusader, Byzantine and Roman eras.

The Old City, like the compound that was neglected for several years after the death of the sheikh, is in severe need of restoration. During a siege in April 2002, in which Nablus’ 150,000 inhabitants were subjected to an 18-day (24-hour) curfew, Israeli missiles completely razed two historic soap factories and destroyed or partly damaged 500 houses and places of worship.

According to a report prepared by several organizations that included the Nablus Municipality, An-najah University (under the auspices of the United Nations Development Program, Germany and Japan) many flats in Nablus were occupied “for military purposes,” while “children, women, old and sick people… were kicked out from [sic] their homes and kept as human shields in the seized buildings.” The report indicates that the Israelis bombarded the Old City for ten days using F16s, tanks and Apache helicopters, inflicting nearly $10 million in damages (the Israeli Knesset is currently attempting to pass a bill that will relinquish them of their legal obligation, as an occupying force, to fund the attendant reconstruction needs of these invasions). One of the demolished houses, the report says, was destroyed by military bulldozers while inhabitants were inside. Eight people were killed, 3 of whom were children.

Nablus is world renowned for its olive oil soap production. (Zachary Wales)

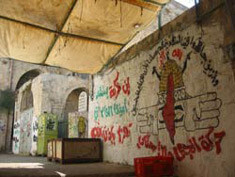

Intifada graffiti near the central souk in Nablus’ Old City. (Zachary Wales)

Although the Nablus Municipality started an urban revitalization program in 1995, the Intifada has brought a new appreciation for the city’s heritage, according to Ola Shaheen, a 21-year-old architecture student at Nablus’ An-njah University who knows Arafat. “The destruction made people appreciate things more. The loss reminds you that you have to keep pushing.”

Arafat’s office itself has been raided at least three times, and though he was never present because of the curfew, the soldiers’ work was apparent as the room would be in disarray, or his materials and books vandalized. Evidence of these raids is still apparent on his office door, which is fractured down the middle, or on the three-dimensional model of Nablus’ topography that hangs on the wall, its cardboard peeled back at the edges.

A stairwell adjacent to the future internet room. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Arafat wants his center to be a refuge from the occupation, but at the same time, he wants to reinforce the cultural heritage that he believes is under attack by the Israelis. In one room, there will be a museum to exhibit Nablus’ traditional soap making methods — Nablus is world-renowned for its olive oil soap, and many believe that soap was invented here.

The upstairs portion of the building is the site of a future library, which will focus on children’s literature and cultural heritage, with one room for group meetings and another for quiet study. Internet infrastructure is already in place, and Arafat envisions scholars and the generally curious alike using the library to research Palestinian history.

In another space there will be an open art gallery that will feature artists on a rotating basis in addition to children’s art workshops. Arafat recognizes the importance of such spaces for children given that so many teaching hours are lost to Israeli curfews. Likewise, these conditions make arts the first subject to be put on the back burner.

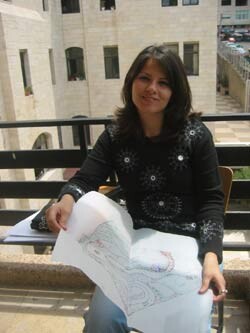

Ola Shaheen with an architectural sketch of a proposed park in Ramallah. (Zachary Wales)

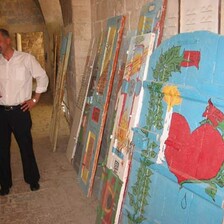

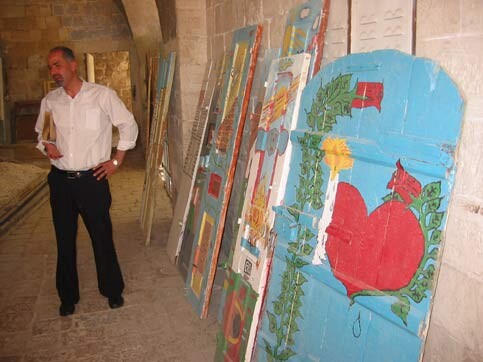

To that end, a children’s art convention was one of the first components of the restoration project. Arafat, himself a father of two, collected many “homeless” doors from houses destroyed in the 2002 invasion. With the support of a Belgian donor and local and international volunteers, 70 children illustrated their dangerous world on both paper and the doors. The paintings were published in a calendar that Arafat sells to help fund the restoration project, which has thus far raised about 3,000 Euros. When the cultural center is complete, the doors will be installed in the soap factory and an outdoor reception area that will house a playground, which are few and far between in the congested Old City.

Arafat is aware of the vulnerability of anything he builds — there’s no telling when the Israelis will strike again, particularly as tensions mount over the Gaza disengagement. He has considered getting the site registered with UNESCO as a world heritage site, but because of its undetermined status, Palestine “is not represented as a country with UNESCO, and only countries can apply” for such status. Besides, Arafat explains, to mark one site off-limits to bombing is to indirectly legitimize the act as permissible elsewhere.

His suggestion to UNESCO is that it holds Israel to international occupation law, which compels an occupying power to protect the cultural sites of its subjects. However, Arafat describes Israel’s attitude as, “it’s our country and we’ll do whatever we want.”

Naseer Arafat and the “homeless” doors. (Zachary Wales)

Arafat continues building regardless. He offers the expression, “soil is merciful for the body, ” adding, “I love the smell of soil when I’m digging.” But why in Nablus, where years of work ca be destroyed by a single missile? “I went to 32 countries in my last twelve years of studying, but this is the one where I want to live.”