The Electronic Intifada Nablus 4 August 2006

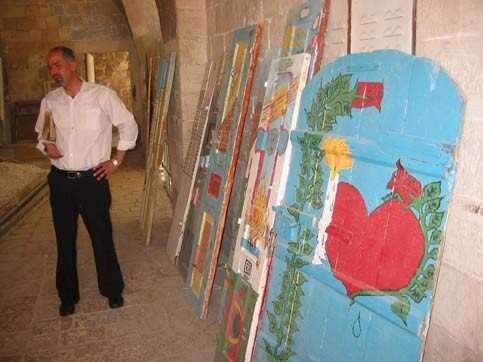

Naseer Arafat and the “homeless” doors. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Why were you traveling in Nablus?

There are beads of sweat on his upper lip, the stubble on his chin is fair. He has found a way to prop his M-4 carbine against the wall behind him so that its sling rests loosely on his shoulder. The blue-eyed corporal next to him slams his palm against a steel beam inches from a woman’s face. She startles and retreats to the imagined line behind us, corrects her hijab along her hair line and stares through him.

Why were you traveling in Nablus, you could have been kidnapped.

Indeed, kidnapped. Like the Brown University student, Benjamin Bright-Fishbein, who allegedly wore his kippah in a Nablus coffee shop last June. What on earth was a Jew doing there? the newspapers insisted. Israelis are forbidden by law to travel in the West Bank, and what made him think his American status made things different? The Jerusalem Post claimed that he “fought off” the kidnappers, when in fact they willfully let him go.

“I still firmly believe … visiting a place so fraught with misunderstanding is the only way to move beyond the conventional wisdom that contributes to the continuation of the conflict,” Bright-Fishbein later told the Brown Daily Herald.

Then there was the woman I met in July. Kidnapped in Nablus’ Balata refugee camp — a “hotbed of militants” if there ever was one — and taken for a two-hour drive. Within the first 15 minutes, she had cleared up her politics and reasons for being there. The remaining time was devoted to resisting invitations for tea, and seeing the sites of the city.

Still another this summer. A foreigner like me, but perhaps prettier. They argued over who would prepare him dinner. They wanted to use him to film a political statement because he was “beautiful”, a word choice that betrayed a less machismo English command — this, accompanied with telling him, “because we love you”, as Arabic’s “nuhebak” makes no distinction between “we love you” and “we like you”.

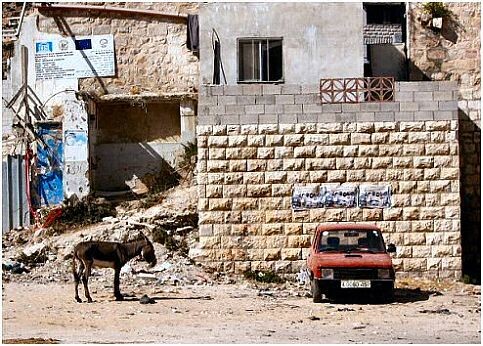

An image from Nablus’ Ground Zero, where Israeli missiles razed two soap factories and several homes. (Photo: Sarah Sachs)

Today there were no kidnappings, only reunions, both voluntary and accidental. It started outside the Old City, where I shook Naseer Arafat’s hand. Good to see you. It seems you’ve put on weight. We walked into the familiar labyrinth of stone tiles, myself, Naseer and two Americans; one a Jewish woman seeing Nablus for the first time, like the less fortunate Bright-Fishbein.

Naseer, one of the most prominent architects in Nablus, is tall and handsome with a salt-and-pepper goatee and gentle voice. He devotes his life work to healing the wounds of this embattled metropolis, particularly the Old City, where there have been about 6,000 architectural resurrections on the area’s 2,600 historic buildings — at least since Israel started using its occupation to strangle the city out of existence — mostly constructed during the Ottoman, Mameluke, Crusader, Byzantine and Roman eras. Not far into our walk we paused before a recent aluminum partition already frequented by the neighborhood’s graffiti evangelists. You remember this, he said. On the other side is Our Ground Zero, where Israeli missiles razed two soap factories and several homes in April 2002. A collaborative of architects is attempting to rebuild it, or to re-imagine Nablus like it was.

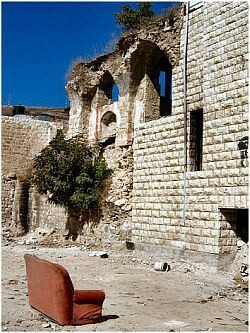

Another image from Nablus’ Ground Zero. (Photo: Sarah Sachs)

They are the products of Homeless Doors Speak, an exhibit that Naseer organized last year to publicize his dream creation. Using property donated by his aunt — a former soap factory and residence once owned by an influential sheikh — Naseer has been constructing a children’s cultural center in the Old City. The homeless doors were gathered from places like Ground Zero-Nablus and brought in for a painting competition by the neighborhood children.

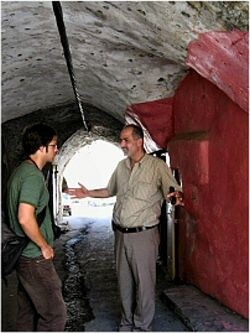

A stairwell in Naseer’s future cultural center. (Photo: Zachary Wales)

Nevertheless, he maintains an annexure for dreams: an overgrown courtyard adjacent to and invisible from the main of the Arafat house. Naseer once told me that he had envisioned this court yard — the last of his tasks — becoming a day care area and safe harbor from the Old City’s rough streets. Today he explained a different idea, too abstract for my mind to follow. With his hands, he painted the dimensions of a child-size airplane. It will be suspended here, at the center of the court yard. The child will sit inside, and a water-powered system of weights and pulleys will give her the sensation of flight.

For the benefit of my companions, I asked Naseer to repeat the story of his own family home, which was demolished by the British — one of Naseer’s ancestors, a resistance fighter, had been taking refuge there — years before Israel’s creation. There is a way Naseer tells stories, so perhaps it was wrong to prompt it. But it never came, as we were interrupted by the arrival of another friend and Nablus local whom I hadn’t seen since last summer. It was time for lunch.

On the way out of the Old City, we passed a town square where Naseer pointed out an estate that once functioned as the guest house for the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. That shop was where the horse stables were; his room overlooked the square. That bullet-riddled clock tower was a gift to the city, over a century old. We winded through the Old City’s ingresses and egresses. Here, the other night an Israeli nail bomb exploded. There, a teenager was killed last week; the Israeli’s said he was a militant. These are Nablus’ unwelcome memories, where Israel’s special forces carry out adventures under the veil of Security Operations: “still water” destroys water supplies; “know your neighbor” blows out walls between homes; “effective kitchen” burns every goddamned thing to the ground.

Naseer shows where an Israeli “nail bomb” exploded in a passageway, its shrapnel still lodged in the walls. (Photo: Sarah Sachs)

Naseer has a theory about the Old City’s design that he calls “random regularity”. Over the centuries, the city crumbles and is rebuilt again, each time with its own functional goal and regularity. It might account for a random threshold with a single vanishing point design, or for the height and width of certain corridors. The most telling narrative in this scheme is that of private quarters, which are often preceded by narrower passages, and sharper curves. The idea, Naseer explained, is to give the psychological impression that the more invisible your destination appears, the less likely you are to venture forward. I looked from the corner where the mausoleum was demolished. Beyond it, the roadway curved and vanished into complete obscurity.

You know, Nablus is not really dangerous if you take off that uniform and leave your gun behind. I know you never will, but I’m only making a suggestion.

He wipes the sweat from his lip and corrects the sling of his M-4 to fit closer to his chest.

Is it pretty in Nablus?

Related Links

Zachary Wales is a regular contributor to Electronic Intifada.