The Electronic Intifada 17 January 2008

The West Bank city of Nablus. (Rami Swidan/MaanImages)

Although it is a small stretch of land, Palestine has many faces, from tiny country villages to bustling cities. Perhaps one of the most impressive places is the city of Nablus. Coming from Ramallah, passage into the city is through the huge, overcrowded Huwwara checkpoint. Having crossed this reversed city gate, set up by the Israeli military in October 2000, the first impression is that of a vivid Arab city, albeit with a sense of tension in the air.

Situated in the north of the West Bank, Nablus is the largest city in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, inhabited by some 134,000 people. Before the second intifada, at which time Israel sealed off the town, Nablus was key to Palestine’s economy. Its most well-known product for centuries has been olive oil soap, a fact testified to by the city’s few remaining traditional soap factories.

But first and foremost, Nablus is home to five millennia of history. The remains of the ancient Shechem a few kilometers outside the current city, with its large dry-stone walls, is a spectacular testimony of the earliest history of this area. Later the Romans came, rebuilt the city and named it Neapolis, from which the name Nablus is derived. The Byzantine period followed, succeeded by the arrival of Islam, crusader invasions and the Ottoman era, all of which left their traces on Nablus.

The market in the Old City of Nablus. (Toon Lambrechts)

It may come as little surprise then that Nablus’ Old City is a place of astonishing splendor. This labyrinth of cobbled streets leads from one surprising sight to another. The Old City’s dense architectural fabric made out of narrow lanes and shady alleyways suggests thousands of stories.

Another inexhaustible source of stories is Majde, International Cultural Coordinator and a first-class Nablus enthusiast. “Most of the Old City dates from the Ottoman era, but some parts go back to the Romans. Al-Balad al-Qadima, as the Old City is called in Arabic, consists of six main neighborhoods, each of which is related to one of the powerful families who controlled Nablus in the past. Nablus never had city walls like Jerusalem for example, so the city’s labyrinth-like design functioned as a defense.”

But the Old City is not a museum. On the contrary, streets are bustling and numerous shops are selling everything from household appliance to sad-looking chickens. “Of course it is like this,” Majde assures. The Old City is still home to more than 20,000 inhabitants who live and work here.”

A recently destroyed house in the Old City.

(Toon Lambrechts)

Nablus has seen a great deal of suffering in recent years. Being a stronghold of resistance, the city has come under severe attack by the Israeli military since the beginning of the second intifada in 2000 until this very moment. “There are still Israeli incursions during the night. Nablus remains under siege, especially the Old City,” Majde explains. Apart from countless human losses and the hardship its residents are facing, Nablus as a city has been wrecked. Many of its historical buildings and architectural elements have been extensively damaged or completely destroyed, a devastating loss for Palestine’s cultural heritage.

The destruction of cultural heritage by Israel in Palestine and in Nablus more specifically, has gone far beyond the pretext of military necessity. “There is significant evidence that Palestinian heritage is being targeted specifically as heritage,” said Naseer Arafat, a Nablus-based architectural conservationist, in an interview with The Independent (UK) in December 2002. As the occupying power, Israel is bound by international humanitarian law. In terms of cultural heritage, this includes the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention and more specifically, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the event of Armed Conflict. Under these treaties, signed by Israel, the deliberate destruction of sites of historical or cultural import is a war crime.

The rationale behind Israel’s devastation of cultural heritage is not hard to grasp. According to Dan Cruickshank, a BBC journalist, “buildings have an immense significance in the area. Ownership of buildings is used to justify political and military positions. Both sides are attempting to destroy each other’s history in an attempt to weaken the sense of ownership,” he explains in an interview with The Guardian.

A shady street in the Old City leads to a place that looks like a parking lot. But it is not. “Here stood one of the oldest soap factories of Nablus. The Israelis destroyed it completely, just before their forces left,” says Majde. He is referring to Operation Defensive Shield in April 2002, when the Israeli military reoccupied several major Palestinian cities. “The factory was more than 400 years old. Together with the soap factory, as much as 25 adjoining houses were completely demolished. On the other side of the road, the facade of an Orthodox church was also damaged. This is the ancient Christian neighborhood, this is why there are several churches here.”

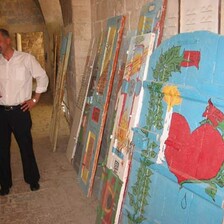

A small gate in the metal fence at the back of the leveled soap factory leads the way to another Nablus ground zero. “This is al-Khan,” Majde explains. “It was something like a large motel for travelers in the Ottoman period. On the ground level there were stables, and there were taverns and lodges on the second floor. A restoration project, carried out by UNESCO, aimed to put it back into use as a cultural centre, a youth hostel and arts and crafts shops. It was also destroyed in 2002.” Although the restoration project continued, the spot currently lies deserted except for the presence of a friendly guard. “Because of the international boycott after the elections and the victory of Hamas, the project has been halted for half a year already,” Majde says.

A once ambitious restoration project is now abandoned due to the international boycott.

(Toon Lambrechts)

Next stop is one of the few remaining Turkish baths in the city. “We have seen three invasions here,” Majde explains. “Each time the bath has been rebuilt. It is about more than just old buildings and stones. It is about our way of life. If places like this, or the old soap factory, or mosques are destroyed, our culture will be destroyed too. That is why it is so important to restore the buildings and our way of life.”

The devastation did not end after the toughest days of the second intifada. The Israeli military still invades the Old City almost every night, looking for wanted Palestinians. The result of this daily violence has mounted up. Majde points out some striking details. “In the entire Old City, there is not one single ancient wooden door or gate left. All of them have been destroyed.”

Next stop is a small green door leading to a courtyard. Two men are busy cleaning up rubble. “This house was destroyed two months ago by the Israeli military,” they explain. “The soldiers claimed that a wanted Palestinian was part of this family, but it is not true. They blew up the house after forcing the inhabitants out. Now 50 people are homeless.” This form of collective punishment and the destruction of property and cultural heritage without military necessity are grave violations of international law. The oldest part of the house was 400 years old, dating form the Ottoman period. Now, it is a pile of rubble, mixed with the family’s belongings.

Just outside the Old City at the end of a back street, another distressing scene reveals itself. This spot, almost completely covered by garbage and locked in between two apartment buildings, used to be a well-preserved Roman graveyard. Now it is a catastrophe. Majde recalls the events that caused this. “In 2002, during the invasion, Israeli soldiers broke the graves with the excuse that weapons could be hidden here. But they took away everything from the site, even the mosaic floors. Now the place is completely neglected.” There were plans to restore the graves with the help of an Italian association, but again, because of the international boycott the project was stopped. “The same thing happened to the museum. It is not clear who plundered the museum, but it took place under full Israeli occupation, so the responsibility lies with them. Not a single thing is left, except for some stone objects too heavy to move.”

But the Palestinians are not without blame in this war against history. Just outside Nablus, near Balata refugee camp, a burned-out ruin testifies to this. The building, known as the Tomb of Joseph, is a sacred Jewish site. In the ’80s, Jewish settlers established a religious school and a small outpost around the shrine, protected by the Israeli army. During the 1996 Western Wall Riots, heavy clashes broke out around the Tomb, and it was damaged. It was then repaired but in October 2000, an angry Palestinian crowd chased away the settlers and the military. The Tomb was then ravaged and has remained so. Garbage litters the blackened floor and the remains of the shrine are illuminated by the sunlight that falls through a large hole in the ceiling.

Some might ask, why bother about old buildings and relics? However, they are not just buildings but places where people live, work and pray. By destroying them, a people’s way of life is also destroyed in the process. And attacks against cultural heritage are attempts to erase the collective memory of a people. That is why these examples are not simply collateral damage in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but silent casualties in a war against history.

Toon Lambrechts is a photographer currently working with the Palestine Monitor in Ramallah. This article was originally published by Palestine Monitor.

Related Links

- Fire unextinguished, Issa Mikel (17 August 2005)

- Breathing life into Nablus, Maureen Clare Murphy and Zachary Wales (8 August 2005)

- Photostory: Nablus’ Old City, Maureen Clare Murphy (10 May 2005)