The Electronic Intifada 19 May 2017

Palestinian women hold portraits of loved ones in Israeli prison during a protest in support of hunger-striking prisoners in the West Bank city of Nablus on 4 May.

APA imagesLatifa al-Naji Abu Humaid’s family are worried about her health. They are trying to convince the 70-year-old that she should start eating again. But Latifa is determined to continue refusing food in solidarity with her sons who are undertaking a hunger strike behind Israeli bars.

“I cannot eat while my sons are starving,” said Latifa, who lives in al-Amari refugee camp near Ramallah, a city in the occupied West Bank. “If they end the hunger strike, I will too.”

Four of Latifa’s sons have been in prison since 2002. All affiliated to al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, the military wing of the Fatah organization, they have been convicted of various charges and sentenced to multiple life sentences for their roles in planning and helping carry out suicide bombings and other armed operations.

The four have joined the mass hunger strike by Palestinian prisoners.

All nine of Latifa’s living sons have been jailed by Israel. A tenth, Abd al-Munim, was assassinated by Israeli forces in 1994 after allegedly killing an intelligence officer in an ambush in Ramallah.

Nasr Abu Humaid, one of Latifa’s sons now on hunger strike, has two children, both in their teens.

“I’m mentally exhausted,” said Nasr’s wife Alaa. “My two sons are worried about their dad and their uncles. They are always asking, what might happen to Dad?”

According to Alaa, Nasr decided to go on hunger strike in protest at how he was being denied family visits.

When his father died two years ago, Israel prevented the family from contacting Nasr and his three brothers in jail. “He [their father] passed away and they did not know,” Alaa said.

Removing restrictions on family visits is a key objective of the mass hunger strike launched on 17 April. Other demands include improved access to medical treatment and ending Israel’s practice of administrative detention – imprisonment without charge or trial.

Around 1,500 prisoners have joined in the hunger strike. An estimated 1,300 are still refusing meals, the Ma’an News Agency has reported.

Isolation

Nasr is being held at Ashkelon prison in southern Israel. All four of Latifa’s jailed sons had been kept there until recently, she said. But since the hunger strike began, two of them have been moved elsewhere.

That appears to be part of a deliberate Israeli policy to isolate prisoners and prevent them from communicating with each other or the outside world. Israel has resorted to the widespread transfer of hunger strikers from one prison to another or between different units of the same prison.

Prisoners have also been placed in solitary confinement and blocked from seeing lawyers.

Najat al-Agha, known as Um Diaa, is another woman who has refused food to support her son’s hunger strike.

Her son Diaa was sentenced to life for his alleged involvement in the killing of an Israeli man in a Gaza settlement in the early 1990s. He is affiliated to the Fatah political party.

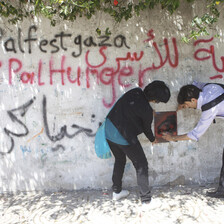

Every day for three weeks, Um Diaa went to a tent erected in support of the hunger strikers in Gaza City.

“How could I bear to eat when he is on hunger strike?” Um Diaa, who lives in the Khan Younis area of southern Gaza, asked. “I couldn’t sleep at night because I was thinking of him constantly.”

Banned from visiting

Um Raed at the Gaza City hunger strike solidarity tent.

Um Diaa has been unable to see her son for the past year. She said she was informed by the International Committee of the Red Cross that Israel has barred her from visiting Diaa for “security reasons.”

The reasons have not been explained. “I don’t know why I’m banned from visiting,” she said. “I only get news about him from other prisoners’ families, when they visit their sons.”

“Diaa was jailed at the age of 16,” she added. “He is now 43. I’m 68 years old and my only dream is to see my son before I die.”

Soon after she spoke to The Electronic Intifada, Um Diaa fainted. She was brought to hospital in an ambulance. Her health had been damaged by going without meals for more than three weeks.

At least eight Palestinian mothers have decided to refuse food in solidarity with their sons on hunger strike.

Samira al-Haj Ahmad, known as Um Raed, is another Gaza woman who felt compelled to act.

Her son Raed al-Hajj Ahmad is being detained at Nafha, a prison in the [Naqab] region of Israel. He was sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment in 2004 after attempting an attack at the Erez checkpoint in northern Gaza.

With her son on hunger strike, Um Raed has decided to stop eating, too. “I don’t even enter the kitchen in my home,” she said. “Whenever I start craving for food, I remember my son and I cry.”

Um Ramzi at the Gaza City hunger strike solidarity tent.

Um Raed was banned from visiting her son a year ago. But Raed’s father has been allowed see him. “He is in high spirits but very sad that I couldn’t visit him in prison,” Um Raed said.

She fully supports Raed’s hunger strike, arguing that it is “the only means by which prisoners can achieve their basic demands.”

Yusra Saleh, known as Um Ramzi, also from Gaza, has two sons – Ramzi and Said – in prison. Both have been jailed by Israel for more than a decade over their activities with Islamic Jihad.

She, too, has been forbidden from visiting her sons for the past year, without Israel giving her an explanation. Because she is unable to communicate with her sons, she has not been able to ascertain if they are also taking part in the fast. But she has joined the solidarity hunger strike.

“I don’t know anything about my sons,” she said. “I only know that Said was in solitary confinement for two years but got out of it a few weeks ago.”

Um Ramzi has been a frequent presence at the Gaza City tent in support of the hunger strikers. The distinct possibility that prisoners will die during it has filled her with dread.

Echoing the views of many Palestinians with loved ones in prison, she said: “I just hope that the hunger strike does not last any longer.”

Maram Humaid is a Gaza-based translator and journalist.