The Electronic Intifada 23 October 2020

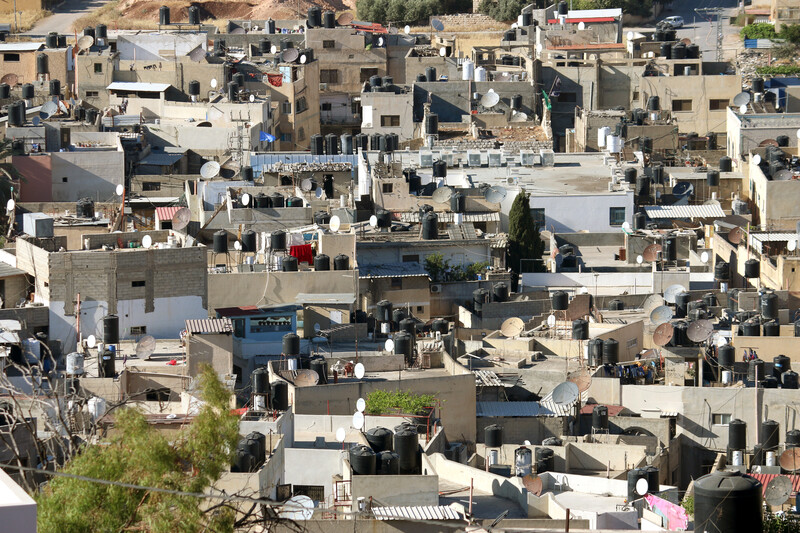

A general view of Jenin’s Ottoman old town.

In the northern West Bank city of Jenin, there was once an airfield, a train station, three cinemas and two major roads connecting the town with the neighboring cities of Nazareth and Haifa.

In 2020, only traces of these now exist and none are used for their original purpose. Instead, the city contains a refugee camp and is surrounded on three sides by a fence erected by Israel’s military as part of the separation wall it has built in and around the West Bank.

Jenin is literally at a dead end.

Once a small agricultural town – mentioned as far back as the 12th century BC Amarna letters – Jenin’s modern history has been marked by political upheaval that has determined its modern urban shape.

Most important of these was the impact of the creation of Israel and the resulting dispossession and forced exile of Palestinians in 1948.

Unlike cities in post-colonial nation-states that emerged across the world in the 1940s and 1950s and inherited pre-formed urban spaces and infrastructure, Jenin and other towns and cities in the West Bank were cut off from their natural hinterland, stunting their urbanization.

Towns located in areas where Israel operates as a state today – including in East Jerusalem and the Golan after 1967 – have been transformed and transfigured to serve the settler community.

When Palestine’s urban loss of the 1948 Nakba is mentioned, Jaffa is usually highlighted. But Jaffa was a cultural center and a commercial gateway that served local agriculture and industry in a way those living in what is known today as the West Bank or the Gaza Strip, including refugees, were never able to recreate.

Jenin at the margin

In his book Jenin City (1964), the academic Kamal Jabarin writes that the town started to expand around its Ottoman center, which still operates as the heart of the city today.

Jenin’s only surviving urban heritage dates from the Ottoman era and includes a marketplace, a government building, a mosque and other buildings.

“The loss of Jenin took place in 1948,” Jabarin told The Electronic Intifada.

The establishment of Israel, he said, “placed Jenin at the margin,” isolating it from the cities and towns it was traditionally connected to and dependent on for trade and cultural and familial ties.

The Saray or the Ottoman government building which was established in 1882 — and became the center of Jenin — is now used as an elementary school.

The Haifa and Nazareth roads were vital arteries connecting Jenin with those two important cities and trading partners, but were abandoned after the 1948 Nakba. Many people from Jenin “were killed for trying to visit their relatives there,” said Jabarin.

The two roads came to life again after Israel’s 1967 occupation of the West Bank.

But these roads have again been closed.

The Nazareth road is today blocked by an Israeli fence and a military checkpoint.

The Haifa road, meanwhile, ends at the Salem military base some 9 kilometers from the city center. Salem is an Israeli military court and detention center.

Gas at the end of the road

Isam al-Amer opened a gas station in 1995 on the Haifa road. Today, it is located right in front of where Israel’s wall blocks passage.

When the gas station opened, it served Palestinians from Jenin who would travel through the Salem military checkpoint here to Haifa and elsewhere.

That checkpoint was closed after the second intifada began two decades ago. And where once 20 people worked, only two are left.

“We’re still working in the hope that the checkpoint will open again,” he added.

Until then, however, he is the owner of the gas station at the end of the road.

The Nazareth road, meanwhile, leads only as far as the Jalama checkpoint just a few minutes from Jenin’s city center.

Muhammad Abufarha holds an old picture of the airfield that was once located in the Jenin area. Today, Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza Strip do not have any airport of their own.

The checkpoint is completely closed for Palestinian Authority-registered vehicles, so any residents who have obtained travel permits from the Israeli military will have to cross on foot.

A few people still remember the airfield area here, which had been established at the end of the Ottoman era in 1917 by German engineers and was later developed by the British authorities to include several aircraft hangars, warehouses and shops.

During the Second World War, the airport was used by both British and US air forces for their operations in the region.

“It could have been turned into a real airport for my town,” Muhammad Abufarha of the nearby al-Jalama village told The Electronic Intifada.

Instead of having an airport, al-Jalama villagers take advantage of the checkpoint to provide services for those hoping to cross, with many “offering their land as parking lots for those leaving their cars to cross,” Abufarha explained.

Refugee sprawl

After the 1948 Nakba, Jenin became a shelter for thousands of refugees who were expelled from their homes in Haifa and 54 villages in northern Palestine.

In 1953, the UN body responsible for Palestine refugees, UNRWA, established the Jenin camp. The refugee camp now has 12,000 residents. The camp is now the heart of a town that contains another 53,000 people.

“Early refugees lived at evacuated British Army barracks, then at the abandoned Ottoman train station, then in UNRWA tents,” said Abd al-Jaleel al-Noursi, who arrived at the Jenin camp in the early 1950s after fleeing Haifa.

After a few years, and with little idea whether they would ever be allowed to return to their homes, residents began replacing their UNRWA tents with mud houses.

In the 1970s, al-Noursi said, the mud houses then became concrete houses.

At the camp’s main square lies the Ottoman train station, which was abandoned in 1948, as were the other railway stations of the West Bank in Nablus and Tulkarm.

Abd al-Jaleel al-Noursi holds an old picture of the Ottoman train station located today at the heart of Jenin camp. The station was used as a shelter by early refugees. Since its abandonment, refugees have been opening some small shops around the building.

Today, there are no rail services available to Palestinians in the West Bank, except for those resident in East Jerusalem.

However, remnants of the abandoned railway are still visible in parts of the West Bank. Five kilometers north of Jenin’s abandoned station, a dirt road marks where the railway used to run, connecting Jenin with Afula and Haifa.

The dirt road is now cut by Israel’s separation wall.

One of the major urbanization challenges in West Bank towns has been the ever-changing planning visions of the different rulers in the area over the last 100 years.

The first structural plan for Jenin was British, said Dina Hamdan, an engineer who has worked with the Jenin municipality.

The next plan didn’t come until 1992.

“The Jordanian and Israeli authorities didn’t give urban sprawl serious attention. They were ruling temporarily,” Hamdan told The Electronic Intifada.

As a result, Jenin’s urban sprawl has been a rapid and random process. The presence of the Palestinian Authority has not helped much.

PA planning has been based on what international development aid is available and for what, said Hamdan.

“When we get funding to pave roads, we pave. When we get one for sanitary drainage, we do that. We are lost.”

Hamdan still feels a sense of belonging to Jenin, but it’s complicated.

“There is nothing attractive in the city. We had potential but we lost it.”

Ambitions of the young

In the city center, two shopping malls were recently built, both on the sites of demolished buildings. A third is under construction.

One of them, Burj al-Saa [Clock Tower] is located where Jenin’s last cinema stood before it was demolished in 2016.

Cinema Jenin was one of three movie theaters in the city. None survive today.

Indeed, there are no screening rooms anywhere in Tulkarm, Nablus or Bethlehem – cities that had several cinema halls just a few decades ago. Al-Hashimi Cinema, in Jenin’s Ottoman old town, still stands but has been closed since 2002.

“Every new movie was shown,” said Hanan Sharif, the widow of al-Hashimi’s original owner.

But political instability and two intifadas have affected the cultural sector acutely, in Jenin and across the West Bank. During the first intifada, said Sharif, the family decided to shut down the cinema after her son Fuad was killed by Israeli soldiers.

It opened years later as a wedding hall. But when a second son, Rashad, was killed during the second intifada, the family decided to shut the venue completely.

Al-Hashimi cinema lies derelict. During the second intifada, Israeli soldiers were based on the roof of the cinema, destroying parts of the ceiling.

Reem Arabi, 37, one of Hanan’s daughters, hopes to rehabilitate the cinema in the future despite her concerns that “society may not be interested in cultural spaces anymore.”

“People are not interested in cinemas anymore. They prefer watching TV or surfing the internet.”

Shatha Hanaysha, 27, is a recent journalism graduate who was always opposed to the closing of Jenin’s cinemas, especially Cinema Jenin.

Today, she now finds herself in the position of running a cultural cafe with three friends on the fourth floor of the Clock Tower mall built on it.

“I was against renting a space in this capitalist mall that replaced the cinema,” Hanaysha told The Electronic Intifada.

Nevertheless, the Kafka Cafe and Shop gave Hanaysha and her friends an opportunity to promote cultural events in the city, a mission dear to their hearts even if it is not lucrative.

“It’s not financially viable but it’s part of our vision,” said Hanaysha.

Still, she is frustrated by the city, the lack of prospects for ambitious youth, and the dearth of public spaces.

“Jenin is tough and I feel sad for young people. There are no real cities anywhere in the West Bank.”

Ahmad Al-Bazz is a multi-award-winning journalist, photographer and documentary filmmaker based in Palestine and a member of the Activestills Collective.

Sarah Abu Alrob is a journalist and an audio producer and presenter living in the West Bank, Palestine.

The Israeli military gate that cuts the Jenin-Haifa historical road has been closed since the second intifada. The Salem military court and detention center is seen in the background.

Jenin refugee camp houses over 12,000 people. During the 2002 Jenin massacre, the Israeli military demolished more than 400 homes here.

“The camp is a temporary station until the return,” reads a text placed at the entrance to Jenin refugee camp.

An Israeli military gate and fence cuts across a dirt road where the Jenin-Afula railway used to run.

Palestinian shops at the new Jenin market center. The city attracts hundreds of Palestinian citizens of Israel every Satuday who come to shop for bargains.

A general view of Jenin’s unplanned and sometimes random sprawl.

Yet another shopping mall is being built in the heart of Jenin. Engineer Dina Hamdan argues that such construction in the city center is a ”big mistake.”

Young people at Kafka Cafe and its view of Jenin’s crowded center.