The Electronic Intifada 22 March 2011

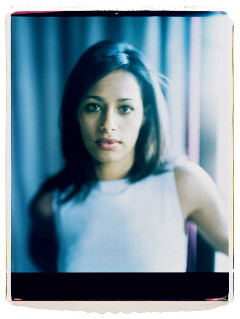

Rula Jebreal

Ali Abunimah: Miral was shown on 14 March at a special screening in the UN General Assembly despite objections from the American Jewish Committee and from Israel. How do you think this attempted exclusion and censorship of your film connects you to the experiences of other Palestinian writers and artists?

Rula Jebreal: We go all through the same process which is as soon as we start talking about our stories, our issues — not even getting into the politics but just explaining how we live our lives under military occupation or what we go through, our suffering — immediately there’s a knee-jerk reaction. And it’s a preventive reaction designed to shut down the conversation and censor it. They want to make us speechless.

There’s an agreement, there’s a complicity with the media because it’s kind of a taboo in the mainstream to talk about Palestinian issues, especially Palestinian stories.

The fact that we showed Miral in the General Assembly which is in a way my story but also it’s the story of four women of different generations, who lived in Palestine between 1948 and 1993, up to the Oslo agreement, to show it inside of the General Assembly is a huge achievement.

AA: What was the reaction at the General Assembly?

RJ: We had previously met Joseph Deiss, the president of the UN General Assembly [a former foreign minister of Switzerland] and showed him the movie. He loved it. He immediately thought that it would be great to host a screening and he wrote a letter saying, absolutely, yes. I went to friends and companies and to ask them if they could economically support releasing the movie. The Gucci company actually paid for the premiere [at the UN] and other friends put their own money up just to bring some publicity to this movie.

There were 1,700 people, everybody was super excited. Before the screening we asked “Is there any Jewish group here from or anyone from the American Jewish Committee [which had strongly objected to the screening]?” There was a total silence.

AA: To be clear, you had wanted the groups criticizing the movie to come and see it?

RJ: Absolutely. Of course I wanted them to come and see it, come and see what’s happening in that country. Instead of defending in a way blindly a state that commits mistakes, why don’t we sometimes hold up a mirror and see what this state is doing? We support Israel with millions of dollars and at the end when they build settlements and then we tell them settlements are illegal and immoral and it brings the military inside the West Bank and Gaza and that the nature of military occupation is violence which brings more violence. They don’t want to hear that.

AA: It’s certainly very unusual, perhaps even unprecedented, for a movie that begins with the Nakba — the expulsion of the Palestinians in 1947-48 — to go on general release in US cinemas. How did this come about and what other resistance did you meet?

RJ: The movie was shot entirely in Palestine and Israel and it was sponsored by the French company Pathe. The owner of the company loved the story, read the book and embraced it. But even he was told by people inside the company, “Are you out of your mind? This is a hot subject.”

And when we wrote the script we had so much pressure also. For example, we went to Israel and Palestine to go location scouting. We wanted to shoot inside of a prison. So the location manager without telling us sent a script to the IDF [Israeli army] so they could give us a location which was a prison that is not even used in Jaffa, in an Arab area. They wrote us a letter saying that it’s an insult to ask for the right to use that location because this script is “anti-Israeli.”

Then I was also told by a journalist in Rome who had had dinner with the Israeli ambassador, that the ambassador had received a letter from the Israeli ministry of foreign affairs warning that there’s an “anti-Israeli” movie coming out. We were still shooting the movie, but immediately there was a reaction!

After we started the release in Europe there was attack after attack in the media saying that the movie is one-sided, it doesn’t tell the whole story and it’s a mediocre movie. I understand if you don’t like the movie, but to try to tell people “don’t go see this movie because it’s not only bad, it portrays Israelis as all evil, the Palestinians as all good?”

So it was really very tough. And in the end we decided on March [for the US release] but personally I didn’t feel that the focus of the Weinstein Company [the US distributor] was all in this movie, the focus of the company was on different subjects.

AA: Miral is described as a semi-autobiographical novel and the story of the title character is based on your own life. But it starts with Hind Husseini, who is a legendary person among Palestinians, but many other people probably would never have heard of her. Who is Hind Husseini and what is her legacy for Palestinians and for you personally?

RJ: Hind Husseini was my teacher, my mentor; she was like my mother. The woman who saved my life and put me on the path to education. She’s the woman who in 1948 found 55 kids in a street in Jerusalem at six o’clock in the morning. They were the survivors of the massacre at Deir Yassin. She took them home and from that day her home became Dar al-Tifl [The Children’s Home].

Hind Husseini raised thousands of girls, gave them hope, a future, possibility and she gave us confidence that we could do anything. And that is why during the first intifada [the Palestinian uprising from 1987-1993] she sent us to the refugee camps because she wanted schools to be reopened [as Israel closed all schools down for more than two years].

I was five when I went to Dar al-Tifl, my sister was four — after my mother committed suicide — my sister was crying the whole time. And the only way to put her to sleep, to calm her down, was to tell her stories. I became a storyteller and a writer from that moment without knowing that I was studying my own subject.

AA: You came of age during the first intifada and you were also arrested and tortured by the Israelis and that experience is depicted in the film.

RJ: During the intifada, Hind closed her eyes sometimes when we would go to demonstrations. She didn’t like it but she knew that we were doing it. I would wake up at six o’clock in the morning, go to school, finish school at 1:30pm, have lunch, finish my homework, and then go to demonstrations. That was my daily life during the first intifada. Nobody could stop me.

What happened to me was nothing compared to what happened to the other kids because I was born in Haifa.

AA: So that made you an Israeli citizen legally?

RJ: Exactly. Legally I’m an Israeli citizen and because of that fact I was beaten up in a way not to harm me, to hurt me, but not to harm me. Many times during demonstrations policewomen or soldiers, they would kick you and punch you in the face, grab your hair, they didn’t care. I had settlers throwing stones at me when I went to Hebron and spitting in our face, calling us all kinds of names, only because we went to Hebron to open a school. For them, that was outrageous.

AA: You talked about this story, the book and the film, as a story of four women and it addresses really difficult experiences including domestic violence and sexual assault, time in prison, alcoholism and one of the characters, based on your mother, commits suicide. How hard was it for you to write about these subjects, especially since they draw on your own life?

RJ: My mother was raped and she committed suicide. It was harder for her to live that life than for me to write about it. But writing about it made me process it.

When I went to Europe for a while I didn’t think about it and I was so busy raising my child, working, studying. But I never really addressed it. It kept coming back. Every time I would watch television I would see the second intifada or Iraq War or certain things, I would have terrible reactions. I couldn’t sleep and it would depress me.

So I thought I need a moment to process this and go through it. So I wrote about it and I didn’t know if I would, if I could be honest. Especially in our culture to talk about rape and sexual harassment. It is actually shameful for the victims, not for the criminals. So my family wasn’t really very happy. But I needed to relieve myself from this heavy burden.

When we went and we shot the movie there was one moment where the actress couldn’t swim and she told us that only five hours before the shooting and Julian [Schnabel] said to me, “Can you do this scene?” I thought he was out of his mind. But I understand what it meant for my mother actually to go through this when my head was under the water.

AA: So in the film, another actress (Yasmine Elmasri) plays the character based on your mother but for that scene where she commits suicide by walking into the sea, you actually played that yourself?

RJ: Yes, and it was very brutal, very dramatic and very painful. But in that moment I felt I relieved myself from that tragedy. It wasn’t mine anymore. It didn’t belong to me anymore.

I felt that I understood even what she went through. I didn’t really have any resentments and I had more understanding of it. And I felt forgiveness in a way.

I remember I was swimming and it was dark and I was thinking, “My god, I can’t even believe this.” What you feel when you’re writing, and especially when you’re acting, doing something that somebody else did but you know that it’s deeply self-destructive, you become that person. It takes over. That energy takes over. And I didn’t hear them when they said “cut.” I kept on swimming and I felt I was almost crying under water. And when they came and grabbed me it felt very very hard for me. I was crying and shaking and in that moment I felt finally I was dealing with this.

AA: When Miral came out in Europe last year, the film received some quite critical reviews. Does that make it more challenging to release it in the US on top of the political controversies surrounding it, and how have you responded to the criticism? I understand the film was also re-edited; was that partly a response to the criticism? What kind of decisions went into that?

RJ: More of the re-editing came because of the rating. The MPAA, which is the organization that gives the rating [and initially gave Miral an R rating] said it shouldn’t be shown to teenagers. But you know, we made this movie for teenagers. Everything was made under the guidelines of the MPAA. So we re-edited the movie and showed it to them and they changed it to PG-13.

Sometimes art is ahead of time. Sometimes movies and narrative are ahead of time. I think sometimes people need to process things, to have a long relationship with that picture, that subject matter. I understand that not everybody might like this story — which is fine. It’s not made to please everybody. But it’s made to generate debate and to promote one thing — that each person has the right to tell their own story. And this is a story that was never told here in the United States — especially with a mainstream audience. So it has the right to be shown and whether you like or not, give it a chance. Go see it, and whatever you think, it becomes a journey, a personal journey for each person.

Photo courtesy of Rula Jebreal.

Ali Abunimah is co-founder of The Electronic Intifada, author of One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse and is a contributor to The Goldstone Report: The Legacy of the Landmark Investigation of the Gaza Conflict (Nation Books).

Related Links

- Film review: Palestine as Hollywood fantasy in “Miral”, Omar El-Khairy, 23 November 2010