The Electronic Intifada 23 November 2010

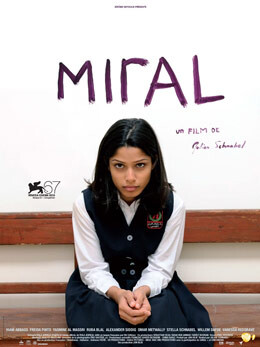

Admitting to not knowing much about the Palestinian people until he met journalist Rula Jebreal and read her semi-autobiographical novel on which the film was based, Schnabel’s film chronicles the lives of three generations of Palestinian women from the 1947-48 dispossession or Nakba through to the 1993 Oslo accords. The film begins with wealthy Jerusalemite Hind Husseini, played with contained strength and warmth by Hiam Abbass, who, after stumbling across a group of orphans left traumatized by the 1948 war, sets up the Dar al-Tifl orphanage to house and educate thousands of abandoned girls. The film then jumps to the 1960s, shifting focus to two other women. Nadia, a young runaway racked by abuse and alcoholism, is arrested for punching a Jewish woman on a bus in Jerusalem. While in prison, she meets Fatima, a nurse sentenced to life for attempting to detonate a bomb in a downtown cinema. Upon her release, Nadia marries Jamal, a stereotypically “god-fearing” Muslim. The narrative then begins to take predictable turns as it follows the fortunes of their daughter, Miral, who is sent to Hind’s orphanage. The passionate teenager, played by Slumdog Millionaire star Freida Pinto, ends up being torn between the will of Hind and her father — who urge her to focus on her education — and her love for Hani, the contrived Palestine Liberation Organization activist — typically dangerous, dark, handsome and ultimately untrustworthy. With the suffering and violence of the military occupation serving only as a backdrop, the clichéd turmoil, which drives Miral’s actions through to the film’s limp climax, simply ends up lacking any kind of dramatic impact.

Schnabel’s last three features — Basquiat, Before Night Falls (Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival 2000) and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Best Director Cannes Film Festival 2007) — have created a wholly justified reverence for his work. However, whereas Schnabel’s previous films have focused on the intimate struggles of one man’s life, Miral’s four protagonists, with their simplistic characterizations, emerge with no real inner life. Structured around a single issue, Miral exhibits none of the complexity, subtlety and humanism that have come to characterize Schnabel’s work. There are, however, a few fleeting moments of worth. When Schnabel employs his usual jagged, impressionistic style — characterized by the handheld camerawork of Eric Gautier — on the fragmented Palestinian landscape, it proves both visually and emotionally arresting. Using techniques reminiscent of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Nadia’s abuse at the hands of her father, for example, is shown through her eyes alone — a pole from her bedstead slowly appears and disappears as the camera follows the harrowing thrusts of her father. Other scenes — most notably the opening tracking shots of a fractured land — are shot with Schnabel’s signature blend of hallucinatory and microscopic detail. Miral is thus most interesting when Schnabel’s hand is freed from Jebreal’s didactic, overwritten script. Other moments, however, highlight the film’s inability to deal with the violence. This is most troubling is an over-stylized and ultimately ambiguous sequence that makes use of a rape scene from Roman Polanski’s Repulsion as the bomb left by Fatima in a Jerusalem cinema is about to go off. Thus, in Schnabel’s film, the violence of the occupation is never dealt with explicitly and ends up being either aestheticized, as in the above scene, or completely occluded.

The film, which has just finished the circuit of European film festivals, has received rather scalding critical reaction. Peter Bradshaw, the Guardian’s film critic, called Miral “a disaster” after its Venice screening. While the leading entertainment-trade magazine Variety questioned the film’s narrative choices, asking, “why, of the countless stories that have been told about the conflict, this one was worth singling out?” What is most interesting is that a film that reeks of liberal morality has kowtowed to commercial imperatives and the assumed tastes of mainstream Western audiences. There are distracting and miscast cameos from Willem Dafoe and Vanessa Redgrave, an incongruous soundtrack featuring Tom Waits, and the film is predominately in English, with only brief interludes in Arabic and Hebrew. However, most notable is the role played by Frieda Pinto. Her casting has caused some unease amongst those who feel she lacks the authenticity to play a Palestinian orphan. However, Pinto’s casting represents something far more interesting. It shows more clearly the film’s attempt to repeat the international success of Slumdog Millionaire by casting Pinto as a modern day Pocahontas who can be effectively transplanted from a Mumbai slum to an orphanage in Jerusalem.

Some commentators have put the previously Oscar-nominated director’s uncharacteristic dud down to a simple blurring of personal judgment. Much has been made of the real-life romance between Schnabel and Jebreal that helped bring the film to fruition. Although there is an obvious danger of over-psychoanalyzing their “cross-cultural” relationship, there is something to be said about how it is has undoubtedly influenced the film’s broader politics. Firstly, by individualizing and personalizing politics, Jebreal’s script serves to occlude the crucial collective strategies that are employed in times of struggle. Its critique of the various strategies chosen by Palestinians is both subtle and surreptitious. By showing each generation as disillusioned and fundamentally broken by their own resistance to the occupation, Miral presents such efforts as self-destructive and futile.

Secondly, and equally insidious, is the film’s portrayal of Palestinian men. Apart from the benign figure of Jamal, Palestinian men spend their time raping, drooling over or marrying off their daughters. This goes hand-in-hand with how both Jebreal and Schnabel have chosen to repeat the now-popular cipher of the beautiful, strong and liberal third world woman. This disobedient figure drinks, smokes and struggles against the pressures of forced marriage so as to find freedom and (un)forbidden love in the West. More generally, a film that spends more time in the posh American Colony hotel in Jerusalem than the streets of the West Bank and Gaza — which is rendered completely inconspicuous in the film — cannot be seen as representative of the Palestinian experience. Moreover, the unproblematic reification of the Husseini family, and in particular Hind’s Mother Teresa-like nonviolent teachings as some kind of counterpoint to strategies of the first Palestinian intifada are more than troubling. The other core ideological strand that runs through Miral is that of coexistence. This comes across most vividly through Schnabel’s distorted representation of ordinary Israelis as refuseniks who spend their time skinny dipping, listening to The Who and the Rolling Stones and have no qualms about dating Palestinians. In order to make this simplistic rendering of the 1960s work, Schnabel not only misrepresents Israeli society, but also presents a bastardized account of the first intifada. The myth of coexistence is only made conceivable through the occlusion of the intimacy of the occupation and the deeply flawed presentation of the Oslo peace process — this moment of (false) hope that was apparently snatched from us and needs to be rekindled.

Much has been made of the film’s supposedly pro-Palestinian stance and what has been presented as Schnabel’s bold position on the Israel-Palestine conflict. People will point to its depiction of everyday Israeli abuses and the interrogation scene in which Miral is whipped by Israeli security forces, but the calculated script lacks the political engagement and personal imagination necessary to rupture the dominant discourse on Israel and the Palestinians. Its mix of the harsh faux-reality of Lee Daniel’s Precious and Disney-like optimism of Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire makes it an ideal film to secure the pity and sympathy of mass audiences. Playing cheap binaries may make for entertaining viewing, but it does not help create the dangerous conditions of possibility that are necessary if the discourse is to be subverted. With its generally earnest, reverential tone that never quite rings true, Miral ends up as a dreamscape of how the West would like to see Palestinian society behave. Miral will undoubtedly capture a wider audience than Elia Suleiman’s The Time That Remains, but it lacks the absurd humor and timely shifts in tone that make Suleiman’s film a modern masterpiece.

This article originally misidentified the actor who plays Hind Husseini’s character. The article has been corrected to show that the actor is Hiam Abbass.

Omar El-Khairy (omarelkhairy AT gmail.com) is a playwright and PhD candidate in political sociology at LSE. He resides in the gutters of the English language.