The Electronic Intifada 31 March 2008

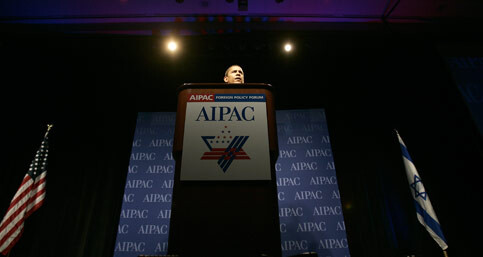

Senator Barack Obama addresses the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) forum on Foreign Policy in Chicago, March 2007. (Jeff Haynes/AFP/Getty Images)

US senator Barack Obama was widely hailed for his 18 March speech calming the media furor about the sermons of his pastor for twenty years Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Wright’s remarks, Obama said, “expressed a profoundly distorted view of this country — a view that sees white racism as endemic, and that elevates what is wrong with America above all that we know is right with America; a view that sees the conflicts in the Middle East as rooted primarily in the actions of stalwart allies like Israel, instead of emanating from the perverse and hateful ideologies of radical Islam.”

It might seem odd for Obama to mention Israel and “radical Islam” in a speech focused on US race relations, especially since Wright’s most widely reported comments were about America’s historic and ongoing oppression of its black citizens.

But for months, even before most Americans had heard of Wright, prominent pro-Israel activists were hounding Obama over Wright’s views on Israel and ties to Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. In January, Abraham Foxman, National Director of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), demanded that Obama denounce Farrakhan as an anti-Semite. The senator duly did so, but that was not enough. “[Obama has] distanced himself from his pastor’s decision to honor Farrakhan,” Foxman said, but “He has not distanced himself from his pastor. I think that’s the next step.” Foxman labeled Wright “a black racist,” adding in the same breath, “Certainly he has very strong anti-Israel views” (Larry Cohler-Esses, “ADL Chief To Obama: ‘Confront Your Pastor’ On Minister Farrakhan,” The Jewish Week, 16 January 2008). Criticism of Israel, one suspects, is Wright’s truly unforgivable crime and Foxman’s vitriol has echoed through dozens of pro-Israel blogs.

Since his early political life in Chicago, Barack Obama was well-informed about the Middle East and had expressed nuanced views conveying an understanding that justice and fairness, not blinkered support for Israel, are the keys to peace and the right way to combat extremism. Yet for months he has been fighting the charge that he is less rabidly pro-Israel than other candidates — which means now adhering to the same simplistic formulas and unconditional support for Israeli policies that have helped to escalate conflict and worsen America’s standing in the Middle East. Hence Obama’s assertion at his 26 February debate with Senator Hillary Clinton that he is “a stalwart friend of Israel.”

But Obama stressed that his appeal to Jewish voters also stems from his desire “to rebuild what I consider to be a historic relationship between the African American community and the Jewish community.”

Obama has not addressed to a national audience why that relationship might have frayed. He was much more candid when speaking to Jewish leaders in Cleveland just one day before the debate. In a little-noticed comment, reported on 25 February by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Obama tried to contextualize Wright’s critical views of Israel. Wright, Obama explained, “was very active in the South Africa divestment movement and you will recall that there was a tension that arose between the African American and the Jewish communities during that period when we were dealing with apartheid in South Africa, because Israel and South Africa had a relationship at that time. And that cause — that was a source of tension.”

Obama implicitly admitted that Wright’s views were rooted in opposition to Israel’s deep ties to apartheid South Africa, and thus entirely reasonable even if Obama himself did “not necessarily,” as he put it, share them. Israel supplied South Africa with hundreds of millions of dollars of weaponry despite an international embargo. Even the water cannons that South African forces used to attack anti-apartheid demonstrators in the townships were manufactured at Kibbutz Beit Alfa, a “socialist” settlement in northern Israel. Until the late 1980s, South Africa often relied on Israel to lobby Western governments not to impose sanctions.

And the relationship was durable. As The Washington Post reported in 1987, “When it comes to Israel and South Africa, breaking up is hard to do.” Israeli officials, the newspaper said, “face conflicting imperatives: their desire to get in line with the West, which has adopted a policy of mild but symbolic sanctions, versus Israel’s longstanding friendship with the Pretoria government, a relationship that has been important for strategic, economic and, at times, sentimental reasons” (“An Israeli Dilemma: S. African Ties; Moves to Cut Links Are Slowed by Economic Pressures, Sentiment,” The Washington Post, 20 September 1987).

In 1987, Jesse Jackson, then the world’s most prominent African American politician, angered some Jewish American leaders for insisting that “Whoever is doing business with South Africa is wrong, but Israel is … subsidized by America, which includes black Americans’ tax money, and then it subsidizes South Africa” (“Jackson Draws New Criticism From Jewish Leaders Over Interview,” Associated Press, 16 October 1987). As a presidential candidate, Jackson raised the same concerns in a high profile meeting with the Israeli ambassador, as did a delegation of black civil rights and religious leaders, including the nephew of Martin Luther King Jr, on a visit to Israel. For many African Americans, it was intolerable hypocrisy that so many Jewish leaders who staunchly supported Civil Rights and the anti-apartheid movement would be tolerant of Israel’s complicity.

Thus, Reverend Wright, who has sought a broader understanding of the Middle East than one that blames Islam and Arabs for all the region’s problems or endorses unconditional support for Israel, stood in the mainstream of African American opinion, not on some extremist fringe.

That is not to say that Jewish concerns about anti-Semitic sentiments among some African Americans should simply be dismissed. Racism in any community should be confronted. But as they have done with other communities, hard-line pro-Israel activists like Foxman have too often tried to tar any African American critic of Israel with the brush of anti-Semitism. Why must every black candidate to a major office go through the ritual of denouncing Farrakhan, a marginal figure in national politics who likely gets most of his notoriety from the ADL? Surely if anti-Semitism were such an endemic problem among African Americans, there would be someone other than Farrakhan for the ADL to have focused its ire on all these decades.

By contrast, neither Senator Joe Lieberman (Al Gore’s running mate in 2000 and the first Jewish candidate on a major party presidential ticket), nor Senator John McCain have been required so publicly and so repeatedly to repudiate extremist and racist comments by Israeli leaders or some well-known radical Christian leaders supporting the Republican party. Foxman, whose organization devotes enormous resources to burnishing Israel’s image, has rarely spoken out about the escalating anti-Arab racism and incitement to violence by prominent Israeli politicians and rabbis.

That is no surprise. African Americans, Arab Americans and Muslims all share some things in common: individuals are held collectively responsible for the words and actions of others in their community whether they had anything to do with them or not. And the price of admission to the political mainstream is to abandon any foreign policy goals that diverge from those of the pro-Israel, anti-Palestinian lobby.

Co-founder of The Electronic Intifada, Ali Abunimah is author of One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse (Metropolitan Books, 2006).

Related Links

- The loneliness of the One-Issue Voter, Laurie King-Irani (4 February 2008)

- Ali Abunimah discusses US presidential candidates on Democracy Now!, Transcript (25 January 2008)

- Questions for Candidate Obama, Bill Fletcher, Jr. (7 May 2007)

- How Barack Obama learned to love Israel, Ali Abunimah (4 March 2007)