The Electronic Intifada 9 May 2007

Film stills from They Don’t Exist (1974)

Hamid Dabashi, founder of the Dreams of a Nation: A Palestinian Film Project, has said that one of the distinguishing qualities of Palestinian national cinema is that it has and continues to be produced during the throes of trauma. This stands apart from other national cinema (German, Italian, and Iranian, to name a few) which came to maturity through dealing with past national trauma. However, there has never been a Palestinian-produced feature film focusing on the Nakba. The forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland during the establishment of the State of Israel, the Nakba is the singular event from which Palestinians — whether living under military occupation, in exile, or under a state apparatus that discriminates on the basis of religion — can trace their current conditions.

Yet, the Nakba is at the core of Palestinian cinema, as exemplified by the Palestinian Revolution Cinema series curated by Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, which was originally presented at the New York Arab and South Asian Film Festival in February 2007 and will show in Chicago this Saturday. The films — produced during the late ’60s through the early ’80s — depict the Nakba not through archive footage of the 1947 and 1948 expulsion but rather through the then-contemporary, alternating images of smiling children in refugee camps (when they were still comprised of tents) and the ghostly trails of Israeli missiles falling from the sky.

The films — all created in exile — document the continued Palestinian experience of Nakba with minimal reliance on factual narration. Rather, it is the images that speak for themselves. In Mustafa Abu Ali’s They Do Not Exist (which takes its name from Golda Meir’s famous quotation in which she denied that there was such a thing as a Palestinian people) women in the southern Lebanon Nabatia refugee camp go about their daily lives — sweeping the floor, kneading dough, tending to the laundry. The only narration is that of a girl reading a letter she penned to a fedayee (freedom fighter), which we hear again a couple of scenes later as a fedayee reads it.

The chronology is loose and non-specific — after these scenes there is propaganda footage of Israeli fighter planes and then an Israeli air raid on Nabatiya (ironically accompanied by classical music) followed by footage of the stunned residents silently observing the destruction of the camp. Witnesses and victims of the air raid are interviewed. Their individual names do not particularly matter because, as one woman who lost her eldest son explains, “This is not happening just to us but the entire Palestinian people.” The universality of the experience is emphasized — the collective trauma of the Palestinians and, as the film brings into context, the imperialist struggles in Vietnam and Mozambique, as well as the genocide perpetrated against Native Americans and that by Nazi Germany.

The film boldly refutes both Meir’s assertion that there is no Palestinian people, as well as Moshe Dayan’s boasting that there is no longer a place called Palestine. And though it is not explicitly quoted in the film like Meir and Dayan, the footage of the camp negates Zionism’s founding myth of “a land without a people for a people without a land.” The film answers these attempts to obliterate Palestinian nationalism with footage of a press conference in which revolutionaries state that Israel’s is a “policy of extermination against our resisting people.” What Israel couldn’t do in 1948 — efface the entire nation of Palestine — would not succeed in the 1970s and to the contemporary viewer, it is clear that if Palestinians have survived all that they have, it is unlikely that this policy of extermination will succeed any time soon.

Film stills from Born Out of Death (1981)

The theme of national continuity makes a profound impact in the haunting Born Out of Death, dedicated to the over 300 killed and thousands more injured during the Israeli bombing of Faqahane, Lebanon on 17 July 1981. There is no voice-over narrative at the beginning of this film, directed by German Monica Maurer, who worked with the Palestine Liberation Organization’s film unit. The frenzied, alternating images of funerals and victims of the bombing — juxtaposed with lingering, quiet footage of the shell-shocked mourners in a cemetery — are all the information we need. Echoing the contradiction of the film’s title, children smile for the camera as they cling to the skirts of crying relatives in the very crowded cemetery. Then quite jarringly comes the narration of a woman who describes herself as Fatima al-Halaby, 21, who was born in the south of Lebanon, married a Palestinian comrade, and then was killed when nine months pregnant. “I was executed by a phantom,” she explains, adding that the second round of shrapnel to hit her opened her womb “like a cesarean.” The surviving fetus is named “Palestine,” and Fatima states, “I may have died but Palestine is still living.”

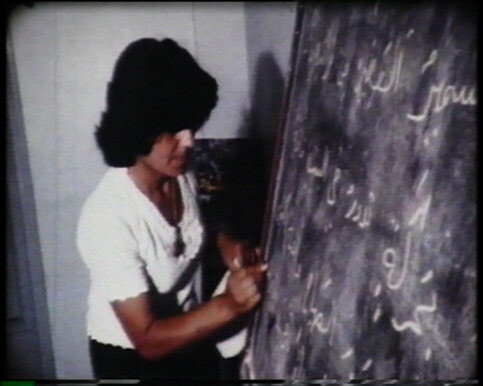

These children born of death (in the more general sense of displacement and war) are at the center of Khadija Abu Ali’s Children Nonetheless. Much like the women doing housework in They Do Not Exist, the imagery of children doing things that children do — drawing, climbing on playground equipment, stringing beads — accompanied by flute and drums with an upbeat rhythm, is contrasted by interviews with and the stories of the children themselves. Seven-year-old Wafa, in a small yet matter-of-fact voice, explains that her parents are dead; her mother was shot through the head and her father stabbed by Phalangists.

Film still from Children Nonetheless (1980)

The children in the film are residents of Beit Sumoud, which houses half of the children who lost their family during the Tel al-Zatar refugee camp siege, during which hundreds of children died and 15,000 residents were forced to flee — half of them children, some of them too small to be able to say their own names. At Beit Sumoud, the children live with surrogate families. The child Jihad was two years old when his mother was martyred while holding him in her arms. Upon arrival to Beit Sumoud, he did not speak and was presumed to be deaf and dumb. However, as a result of the nurturing environment of Beit Sumoud, he now smiles and it is explained, “little by little he became more expressive and willing to talk.”

The experiences of the children at Beit Sumoud are paralleled with those living under Israeli occupation in Palestine. An Israeli newspaper’s investigation of the pervasive exploitation of Palestinian child labor in the Israeli commercial sector (which indicted public figures such as then-general Ariel Sharon), coupled with the testimony of a boy who was arrested, beaten and humiliated in Ramallah, glues together the narrative of suffering universally experienced by the fractured Palestinian nation. And yet we see the children flourish and their joy as they dance the traditional debke dance. And while the older children are shown learning how to shoot firearms, what seems to be the most effective weapon against Israel’s constant threat of effacement is the preservation of the Palestinian narrative and culture.

That these examples of Palestinian revolution cinema — amongst the handful of surviving films after a Palestinian film archive housed in Beirut went missing during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon — are again being screened is an act of resistance against Israel’s historic efforts to efface, outlaw, and appropriate Palestinian culture. They are important not because they are historic curiosities, but because they retain their currency. As Joseph Massad points out in Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema, the founders of the revolutionary film units “were keen on recording revolutionary events, and they did not want to replicate the experience of previous revolutions that failed to record their pre-victory period on film, leaving such tasks to outsiders.” What is so weighty about these films is that they were produced during the midst of trauma, providing a cinematic window unto a specific time of the Palestinian struggle, yet are still totally relevant today as the question of Palestine remains an open one, and Palestinians are still living the legacy of the Nakba.

Maureen Clare Murphy is Managing Editor of The Electronic Intifada.

The Palestine Revolution Cinema series includes AWAY FROM HOME (1969, 11 min.), and THE VISIT (1970, 10 min.), both by Qais il Zobaidi; CHILDREN NONETHELESS by Khadija Abu Ali (1980, 25 min.); THEY DON’T EXIST by Mustafa Abu Ali (1974, 25 min.); KOFR SHOBA by Samir Nimr (1972, 34 min.) [not available at time of review]; and BORN OUT OF DEATH by Monica Maurer (1981, 9 min.) In Arabic with English subtitles. Mini-DV and 16mm. Screening at 8:15 on 12 May 2007 at the Gene Siskel Film Center, Chicago.

Related Links