Electronic Lebanon 9 April 2007

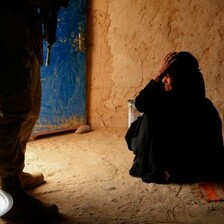

Iraqi refugee Sarah looks at her sleeping daughter Rand as her husband plays with their son 21 March 2007 in a dark and damp room of an aparment in Beirut’s Christian suburb of Dikwaneh which is housing her and her family. Sarah fled war-torn Iraq along with her husband and eight other members of her family a few months ago after her father, an official in the Iraqi education ministry, was shot dead as he was walking out from a school. She and her family are among the thousands of Iraqis living in difficult conditions in Lebanon, desperately awaiting the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to transfer them to a European country. (Marwan Naamani/AFP/Getty Images)

At home in a backstreet of Hayy al-Sillom, one of Beirut’s sprawling southern suburbs’ densely populated and poverty-ridden quarters, Bassem lies on the floor with his multiply fractured leg stretched out in front of him. Though it is broad daylight outside, the windows are shut and the lights are dim in his tiny living room. The air is heavy, almost unbearably so, with cigarette smoke and the stench of urine from a makeshift container he uses, as he cannot get up to go to the bathroom. Covering his body with an old blanket, he surrounds himself only with smokes, piled up ashtrays and the medicines he takes to relieve his pain. His frame reveals he was once an able man, one who could happily take care of providing for his family of five. But the profound sadness in his eyes shows that, today, Bassem is a broken man.

“We fled Baghdad in late 2003,” said Bassem, who is in his early forties. “Security has continually deteriorated since, so I cannot foresee that we will ever return home. I was able to find work as a blacksmith. Though I didn’t make much money, at least we had an income with which I could support my family. After my accident at work, I instead became a burden.”

Relatively speaking, though the Lebanese state has not granted Bassem’s family the right to reside or work in the country, he was fortunate in that his employer funded the treatment he required for his fractured leg. However, with no income, the family is now barely surviving on assistance from Caritas Lebanon and occasional charity from well-meaning individuals. “But the assistance we receive from Caritas is not enough. Now that more and more Iraqis are arriving in Lebanon, the NGOs that previously provided support to Iraqis are badly overstretched. As time goes by, they are able to help us less and less,” Bassem said. “I don’t know what will happen to us in the long run.”

Estimates for the number of Iraqis who have fled to Lebanon ever since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 vary. While the Beirut office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that approximately 40,000 Iraqis are currently in Lebanon, security officials the Lebanese Ministry of Internal Affairs say they believe the number is actually closer to 100,000.

By any count, the number is far smaller than in Jordan or Syria, both of which directly border Iraq. According to a UNHCR press release issued 23 March, Jordan is hosting 750,000, and Syria one million. As is the case for Lebanon, other sources say the figure is higher in both cases. At any rate it is in Jordan and Syria that the vast majority of the estimated two million Iraqis who have fled their country since the 2003 invasion are seeking refuge. Another two million are reported to be displaced inside Iraq.

The figures for all three countries constitute a sharp contrast with that of Iraqis seeking asylum in industrialised countries. UNHCR says the number of Iraqis applying in industrialised countries rose from a total of 12,500 in 2005 to 22,000 in 2006. “Sweden was the top destination for Iraqis in industrialised countries in 2006, with some 9,000 applications, followed by the Netherlands (2,800), Germany (2,100) and Greece (1,400),” the UNHCR statement reads.

At present conditions for Iraqis in Jordan and in particular Syria are poor. Neither country is signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and are therefore not bound to guarantee refugees protection. Instead, incoming Iraqis are classified as illegal migrants. Only Syria, according to International Medical Corps findings, guarantees access to public health and education services. In Jordan, the number of Iraqis now accounts for at least a full fifth of the total population, and are hence perceived as constituting a burden to an already fragile economy.

As for refugees arriving in Lebanon, in response to the growing influx and bearing in mind the continual deterioration of security in Iraq, UNHCR Lebanon has provided Iraqis from Baghdad and southern Iraq with prima facie recognition as refugees ever since February 2007. However, fewer than 10 percent of Iraqis arriving in Lebanon actually register with UNHCR, according to Carole El Sayed, assistant community services officer for UNHCR Beirut. Such recognition affords the refugees partial protection: resettlement is by no means a right, nor is full protection. Lebanon, like Syria and Jordan, is not a signatory to the Refugee Convention. The Lebanese authorities therefore have little regard for proof that UNHCR has recognised an Iraqi as a refugee; in practise, they are illegals. “Because of this, many feel there is no point in registering with UNHCR at all,” said El-Sayed.

In addition, Iraqis in Lebanon fear they may be detained and ultimately deported should they be intercepted by police on their way to the UNHCR office in Verdun, west Beirut. “We don’t know where we stand with regards to the security forces,” said Moufiq, also from Baghdad. “My two nieces are now in jail. They became my responsibility when my brother was killed in Baghdad last year. They were caught trying to get into Lebanon from Syria — they were travelling here to come and join me and the rest of my family. They have been in prison for 23 days. Once their period of detention hits a month, I don’t know what will happen to them. I need to do something, or else they will get sent back to Iraq, where they cannot be safe.” At the time of writing, his nieces were being held in Tripoli, north Lebanon. As for his fear for their safety in Iraq should the state deport them, he has strong grounds: his 24-year-old son and his ageing father were killed in Baghdad before they were ever able to flee the violence.

Iraqis usually enter the country on a one-month tourist visa, or, as was the case with Moufiq’s nieces, they are smuggled in across the Syrian border for $100 to $150 a person. Leniency with regards to the visa situation has been reported, by Iraqis, UNHCR and the Lebanese authorities, to be relative. “Bear in mind,” said Pierre Ephrem, in charge of dealing with non-Palestinian migrants at the General Security branch of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, “that unlike Western countries we are still for the most part issuing visas, either on the border or from the Lebanese embassy in Baghdad. What we cannot condone after the visa expires, however, is that they remain as illegal migrants.”

For the vast majority of Iraqis, Lebanon is perceived as a transit point on the road to a Western country. Smugglers are currently active in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, promising refugees safer lives for the most part in the EU. Smugglers are reported by social workers in Sweden — who spoke on condition of anonymity — to be paid up to $5,000 to cover the cost of illegally transporting Iraqis out of the Middle East altogether. Often, the head of a household will take the risk alone, hoping that the costs of family reunification will at least be partially covered by the International Red Cross, which provides subsidies for this process, case by case. The dream of travel, however, is all too often quickly shattered. Neither are visas forthcoming from industrialised countries, nor is the cost of paying a smuggler — a risky process in itself — affordable to the vast majority.

In Lebanon, priced at $4,000 irrespective of nationality, acquiring leave to remain for longer than a month is expensive. “The only way is if we are able to find a sponsor who can give us work and pay for our residence permit,” said Jawad from Baghdad, father of four children. “But it is extremely difficult to find work here. This is partly because the Lebanese employment situation is pressured as it is, and partly because there is such heavy reliance on employing day-workers without guaranteeing them any rights or continuity. In addition, we are scared we’ll get arrested if we leave the house, so we spend most of our time indoors anyway.” Jobless, the possibilities Iraqis have of ever paying their way to the West are vastly diminished.

It appears that for a great number of the Iraqis arriving in Lebanon from Syria, it was the perilous security situation there that forced them to flee for a second time. Numerous Iraqis, including Jawad and his family, were subject to threats by Iraqi militia members with links in Syria. “Supporters of the Mehdi Army are working in Syria, and the Syrian authorities are turning a blind eye to this,” Jawad said. “We received threats, and we fled to Lebanon even though we knew the social support network for foreigners would be poorer here.”

The sum of factors working against Iraqis in Lebanon all in all renders their lives extremely difficult and equally unpredictable. “We don’t know how we will ever get out of the situation we are in,” said Jawad, who worked as an engineer in Iraq before he fled. “Before the war, we were safe. We could plan our lives and a future for our children. I had a good job; my wife was a schoolteacher, my brother a doctor, and both my parents academics. Now, my father is dead — he was shot. The rest of us, lucky enough to survive and escape, we are nobody. We are refugees according to UNHCR, but what rights does that recognition really afford us?”

As the number of Iraqis arriving in Lebanon grows, the help NGOs working as implementing partners to UNHCR are coming under increased pressure. The Middle East Council of Churches, for one, has had to diminish its material assistance to Iraqis to a bare minimum over recent weeks, affording them free access only to diapers and sanitary towels, said social counsellor and project coordinator Nanor Sinabian. Caritas Lebanon, which hundreds of Iraqis flock to on reception days, is also running short of funds to help.

“The NGOs have been kind to us, and though they are Christian they have never shown a hint of sectarian discrimination,” said Jawad. “We understand that the more Iraqis there are, the less help we can receive from them. But our situation is growing unbearable. We have spent most of the money the family had saved, and we are now living off the precious little cash my mother was able to salvage from her earnings. My brother’s 10-month-old twins are being fed from cow milk powder for adults, instead of baby formula, because we can’t afford it any more, nor can the NGOs afford to assist us.”

Lebanon’s public services are also notoriously limited. Gaining access to free quality health care is practically impossible for Lebanese, let alone foreigners. Places in public schools are limited too, and although in principle Iraqis have the right to access public education for free, Lebanese children are granted priority in an overly burdened system. An indication of this is that a full 70 percent of children in Lebanon attend private or subsidised schools. Anyway, the angst that Iraqis face renders issues such as education secondary. “In any case, how can we think of sending our children to school if we can hardly guarantee them food and clothing?” Jawad asked plaintively. As a result, his sons have been out of school for almost a year now — a tough pill to swallow for a highly educated family such as his.

While the material insecurity facing Iraqis is a major source for anxiety amongst Iraqis, the longer-term, legal aspect of their status in Lebanon is perhaps even more complicated to resolve. The legal unease is no doubt rooted in the apparent contradiction between the fact that UNHCR works in the country and yet Lebanon is not party to the Refugee Convention. The situation is rendered more complex still because of the specifics of this uneasy relationship. On the one hand, UNHCR says that although it is unable to afford protection to Iraqis it recognises as refugees, it at least intervenes with regards to the issue of deportation, to make sure that no Iraqi detainee is involuntarily deported.

An Iraqi refugee looks out over Amman. Of the estimated two million Iraqis who have fled their homeland, some 750,000 are currently sheltering in Jordan, with the majority living in Amman. Like refugees in Lebanon, they live a precarious existence. (P.Sands/UNHCR)

Furthermore, according to Ephrem of General Security, there is an understanding between Lebanon and UNHCR that no Iraqi entering on a tourist visa will be counted as a genuine refugee. “Legally speaking, if they enter on a visa, then why should we consider them to be any different to any other foreigner?” he said. Thus, according to consultant to the Norwegian Refugee Council Robert Beer, Iraqis are trapped in a Catch-22: either they risk detention by entering illegally — even then never being guaranteed the right to full protection — or they enter legally and can never aspire even to minimal protection from the state.

For now, and so long as the situation in Iraq does not improve or the West does not open its doors to more refugees, Iraqis in Lebanon are forced to live invisibly. Perhaps in a bid to find safety in an organisationally sectarian country, Iraqis are for the most part choosing to live in areas corresponding to their own religious affiliation. In other words, the Shias are seeking shelter in the southern suburbs of Beirut and south Lebanon, and the Christians in east Beirut and beyond, into the mountains. The Sunnis are more difficult to locate, as Sunni-based organisations and charities in Lebanon are less moneyed and less effective in their outreach for the most part than their Shia or Christian-based counterparts. One aspect of this is that mutual community support becomes somewhat easier to come by. With origins in Mosul, Majida, mother of two, has been able to find work cleaning a church near her home in Dikwane, east Beirut. “I don’t earn very much, but I suppose I am better off than many others,” Majida said.

But such division along sectarian lines is, on the long-run, a sad reality for the majority of Iraqis facing displacement. “We never cared in Iraq about who belonged to what religion,” said Jawad’s wife Maryam. “It is a real shame so many of us have had to comply with this terrible trend. It is because of the occupation. Questions of religious affiliation never mattered to any of us before.”

Faced with such a severe set-up, and with full consciousness of the horror that led to their displacement, Iraqis are calling for greater leniency from the West with regards to asylum. “We can’t be here for too long,” said Jawad. “Lebanon is not equipped to deal with us. The country has enough problems of its own to help us. We want to go to a Western country. It is shameful that the US, which is occupying Iraq, is not taking responsibility for our flight.”

For now, the Iraqis must live off and try and feed their children the precious little they have left: hope. At home on a rooftop of a building in the suburbs, barely covered by metal plates, Hussein lives with his four sons, the eldest of whom is 12. “Welcome to my home!” he says with a smile. “I am sorry I can’t offer you better hospitality, but believe me I would if I were in a better situation. Maybe one day, I can invite you to fish.” Watching their father, the boys giggle, and then turn their attention back to their books and games. “My wife passed away last year; I must take full care of the boys now. I am proud of them, they have been strong,” Hussein said. “I paint now, and I sell my paintings for a living.” His work, imbued with rich colour, is in itself an embodiment of the hope he and his sons breathe: fresh, energetic, maximum-scale, featuring images of the Imam Ali, birds, trees, the Virgin Mary.

“We are alive, thank God, and that is in itself an act of resistance. I used to be a well-respected teacher of calligraphy at Baghdad University. Life may be tough now, but I have hope in tomorrow.”

The surnames of all Iraqi refugee interviewees have been withheld, given the sensitivity of their security situation in Lebanon.

Serene Assir is a Beirut and Cairo-based independent journalist and blogger.

Related Links