The Electronic Intifada 9 October 2003

“Red Kafias” (Luke Powell)

In Mind, Body and Soul of Palestine: A Photo Journal Exhibit, time, imagery, and stereotype are challenged and contradicted. Indeed, some of the imagery in the photographs contradict each other, causing the viewer to reconsider what they know about this country called Palestine that is constantly being reported but seldom understood. The show is presented by al-PHAN (which stands for Palestinian Humanities and Arts Now), a Chicago-based not-for-profit organization, and will be traveling around the U.S through next spring. Mind, Body and Soul was reviewed at its Chicago installation, where it was installed at ARC Gallery last September.

The three featured photographers, Steve Sabella, Luke Powell, and Andrew Courtney, document the same geography but with completely different formal approaches. Sabella’s brilliantly colored, large photographs are very different from Powell’s vertical landscapes, which reference Asian scroll paintings in their composition. And Courtney’s quiet black and white meditations seem like they can be read as short poetic phrases because of their considered simplicity.

All three challenge perceived notions of Palestine. Powell’s pastoral landscapes shimmer in their timelessness, betraying notions offered by 19th century visitors like Mark Twain, who wrote that Palestine is a dusty, dirty place inhabited by barbaric, unsophisticated people. The warm, green tones of his photographs also contradict the contemporary perception that Palestine is a country only characterized by violence and fighting.

“Jenin, West Bank, Palestine” (Steve Sabella)

“South Gaza City, Gaza” (Steve Sabella)

Similarly, Sabella’s portraits even contrast each other. They alternately depict children that pose only for the purpose of posing, their tired eyes indicating a lack of enthusiasm, to kids with such broad smiles that they seem to have been transplanted from a Gap catalogue to a refugee camp. These smiling kids do not fulfill their voyeurs’ expectations that refugee children should wear tattered clothes and long faces like one sees in many a “Save the Children” infomercial. Take “Jenin, West Bank Palestine.” Photographed after the Israeli invasion in 2001, it features children playing in what appears to be the foundation of a demolished home. In the forefront is a girl, about seven years old, with windswept hair and such a charismatic smile that the viewer must reconsider his or her cliché ideas of what refugee kids are like.

“Rafah, Gaza” (Steve Sabella)

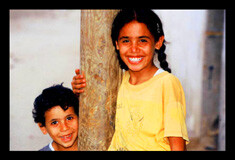

But Sabella, who grew up in Jerusalem’s Old City, leaves his viewers with optimism in “South Gaza City, Gaza.” Taken in what the gallery placard describes as “the poor neighborhood of Tal El Hawa,” two kids, who seem to be brother and sister, smile toothy grins for the camera. The older sister confidently stands in front of what appears to be a wooden telephone pole while her little brother shyly pokes his head out from behind the pole.

Another instance of contrast is the installation of Powell’s landscape “Orchards at Sabastiya” beneath Courtney’s black and white “Souad Srour.” Powell’s photograph, which could have easily been taken a hundred years ago (if color photography technology was available at the time) as it was in 1997. The idyllic scenery recalls sentimental images and perceptions of a part of the world that is so mythologized because of religion. The warm, green grass in the forefront contrasts with the cool background of orchard rows, which recede behind a house whose weathered stones and regional architecture reinforce the overwhelming sensation of timelessness. The tiny figure walking down the gravely road and the equally small horse grazing behind him are suspended in time.

Not so much suspended than trapped in time is Souad Srour, whose portrait is installed above “Orchards at Sabastiya.” Srour, who is not only figuratively trapped by Courtney’s black and white print (Courtney’s black and white photographs feature subjects who seem incapable of movement) is also trapped by her disability — she was paralyzed on the left side of her body after being shot at during the Sabra and Shatila massacres in 1982. The placard explains, “Souad, who does not hide her name, saw most of her family murdered in front of her before the Israeli-supported Phalange soldiers raped her and shot her in the vagina. The bullet remains in her to this day.”

The viewer feels uncomfortable while gazing upon Srour’s portrait. She doesn’t make eye contact with the viewer, prohibiting any personal connection and implying vulnerability, and her disability is made readily apparent by her arm crutches, causing a tiny voice in the back of the viewer’s head to remember mom’s warning that it is impolite to stare at people who “are different.” And because of Srour’s youthful face (the photograph was taken 20 years after the massacre), the viewer is forced to think how young she must have been when she endured such inhumanity.

Equally as jarring is Sabella’s “Jenin, West Bank Palestine” — a different portrayal of the refugee camp than the aforementioned photograph of the same name. Instead of a group of kids playing together and smiling, there is only a lone boy, who seems completely disoriented by the destruction around him. Surrounded by houses reduced to rubble, he seems completely unaware of the photographer as he takes in “what once was a neighborhood he recognized.”

More subtle in its imagery, though no less potent, is Courtney’s documentation of house destruction by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). “Balata Refugee Camp” is complicated despite its deceivingly simple imagery; a little boy props his leg over a huge hole in the wall of his home as his mother stands behind him. All the viewer can see in the home is the lamp hanging from the ceiling. The placard explains that the IDF routinely breaks through walls to avoid going outside, and indeed the hole in the wall found in the image was created moments before the photograph was taken. However, not much emotion can be read on the two figures’ faces, as though such destruction is just a regular part of life.

The success of Mind, Body and Soul” is that viewers will leave the exhibition feeling that they have learned something new about Palestine and Palestinians, or at least will question common conceptions of the place and its people. Perhaps the best example of this is in Powell’s “Red Kafias.” A young boy and his father, both wearing the traditional checkered headdress, smile and exude a familial warmth. Generally, the only kafias, or keffiyehs, Americans see are those worn by shouting young men in footage of protests, or by Yasser Arafat. After seeing Powell’s photograph, room in viewers’ visual vocabulary will have to be made for these common people as well.

Related links:

Maureen Clare Murphy is an Arts, Music, and Culture correspondent for both EI and its sister site Electronic Iraq