The Electronic Intifada 20 October 2010

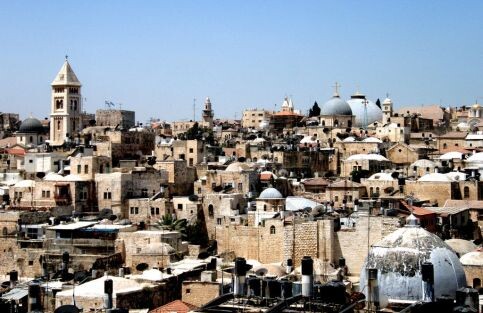

The Old City of Jerusalem. (Flickr)

“I very much want this place to continue being a bit of Palestinian heritage,” says Huda Imam. “A place for people to come and research and do art and have ateliers, or just read and have a cup of tea with mint and feel the Palestinian-ness of the heart of Jerusalem.”

Imam is Director of the Centre for Jerusalem Studies, part of Al Quds University. Situated just a few yards away from the Haram al-Sharif in the Souq al-Qattanin, the Cotton Market in the heart of the Old City of Jerusalem, the center is both an assertion of the city’s Palestinian identity, and an example of the threat that identity faces. While Palestinian lives and homes are threatened by settlers in Silwan, just on the other side of the Haram al-Sharif, the site of the al-Aqsa Mosque, the center is also surrounded, and in its own way equally defiant.

“Some people in our Abu Dis campus say that to have the center here discriminates against Palestinians who cannot access Jerusalem,” Imam admits. “But I discriminate for the benefit of Jerusalem. I want to be able to mobilize people in this part of the city, which is very marginalized and very much under attack by the settler movement.”

The entrance to the Souq al-Qattanin is within sight of several Old City houses taken over by settlers — including former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon — and now draped in Israeli flags. From the elegant courtyard of the center itself Israeli flags can be seen across the rooftops and, Imam says, tunnels are being drilled under the center buildings, heading for the Haram al-Sharif.

A number of controversial tunnels have been dug under the Old City, principally the Western Wall tunnel which was started in the wake of the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. The opening of the tunnel in 1996 by Ariel Sharon, then Israel’s minister of national infrastructure, sparked riots which left eighty dead. Further tunnels by settlers and archaeologists have provoked fears that they are deliberately trying to undermine the foundations of the Haram as-Sharif and open up new routes for control of Palestinian areas.

“It’s tough,” Huda Imam observes. “We’re in a very strategic area.”

The Centre for Jerusalem Studies was founded in 1998, when al-Quds University decided to establish a research base focused on Jerusalem and appointed Huda Imam director. The university had taken out a lease on the fourteenth century Khan Tankiz caravanserai, now a haven of calm where a library, wireless Internet and urns of tea and coffee await guests, but which twelve years ago was “full of garbage.” After a year of cleaning and restoration, the center opened, starting its program with Ramadan Nights storytelling for children, and with a small library mainly drawn from Imam’s personal collection.

Since then, the center has grown to offer bachelor and master degrees in Jerusalem studies and Arabic language courses for foreigners wanting to learn Arabic in “a Palestinian environment, starting with ka’ak [a famous Jerusalem bread coated with sesame seeds], felafel and hummus in the courtyard, which is also an assertion of Jerusalem’s Arabic identities, when it is being very much sold as a Jewish city.”

Artists — photographers, animators, writers and painters — are invited from around the world to hold exhibitions, master classes and ateliers. And it also runs regular walking tours of Jerusalem led by local experts ranging from Armenian photographers to members of Jerusalem’s African-Palestinian community and scholars researching “religious icons, Palestinian food or local rituals.”

The tours have developed both as a means of introducing Jerusalem’s diverse histories to international residents of the city, and as a teaching aid to get students on the center’s courses out of the lecture hall and into the streets and communities of the city they are studying.

“It’s an educational mission but it’s also very much to do with resistance,” insists Imam, “because we’re developing awareness amongst the younger generation who are very much confused by the information and narrative of the Other. As much as I want to respect the narrative of the Other, I very much want to document our own narrative, because it has been seldom documented.”

However, the center’s defense and promotion of Palestinian history, culture and identity within Jerusalem has not gone without interference from the Israeli authorities. Huda Imam has been arrested on several occasions, including in March 2009 during the celebrations for al-Quds - Capital of Arab Culture, which were suppressed, in some cases violently, by the Israeli security forces.

According to an al-Quds University press release on the incident, “The soldiers and police had center center essentially under siege since 7am that morning, they stayed at the Centre to ensure that the children did not put on t-shirts that had the logo of the al-Quds Cultural Capital celebrations on them.”

A year earlier, Imam was also arrested for singing a Palestinian song in East Jerusalem, outside the launch event for the Capital of Arab Culture campaign.

The center itself has also come under attack from the Israeli authorities. In 2009 work began to restore the Hammam al-Ayn, a Mamluk-era bathhouse attached to one side of the Centre for Jerusalem Studies complex. One of two fourteenth-century hammams in this area of the Old City, it had been in use as a public bath until the 1970s, and had already been the venue for several concerts and exhibitions by the center.

But, says Imam, the Israeli Ministry of Antiquities “immediately gave me a court order to stop the works, not only to me personally but also to al-Quds University and to the Islamic Waqf,” the Islamic religious endowment which owns the site.

“It’s very hard for me to come to the center, to the khan, and not to have the door open for people to visit, because of the court order,” she comments.

The legal case over the restoration of the hammam is ongoing. But, says Imam, Israeli attempts the block the center’s work have only inspired more creative ways of spreading its message. It has launched a series of virtual tours of Jerusalem, “allowing people like my nieces and nephews in London or the US, to access the city they are deprived of.” Some Palestinians, thinks Imam, “believe that we’ve lost Jerusalem. But we’re still here, the people are still here, moving, educating, working with artists.”

However, Imam admits, “we also have challenges from the Palestinian side.” When she raised the idea of restoring the Hammam al-Ayn with the Waqf authorities, “they looked at me like I’m talking about a night club.” The Centre’s tours to this year’s Oktoberfest beer festival in the West Bank village of Taybeh also raised some eyebrows.

But Imam insists that for her, the Centre for Jerusalem Studies is about the “openness of what is Jerusalem, what is Palestine.” Center tours include the Haram al-Sharif, but also visits to Jerusalem’s Greek Orthodox, Armenian and other communities, and are open to Israelis “who want to listen.”

Imam says, “The more I see fanaticism on all levels, the more I want to promote dialogue between human beings. But not settlers. Not colonizers. Not those who are coming to take our place and delete us.”

Sarah Irving (http://www.sarahirving.co.uk) is a freelance writer. She worked with the International Solidarity Movement in the occupied West Bank in 2001-02 and with Olive Co-op, promoting fair trade Palestinian products and solidarity visits, in 2004-06. She now writes full-time on a range of issues, including Palestine. Her first book, Gaza: Beneath the Bombs, co-authored with Sharyn Lock, was published in January 2010. She is currently working on a new edition of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and a biography of Leila Khaled.

Related Links