The Electronic Intifada 23 February 2010

Not represented in the official narration of the event is the story of a recent bride whose husband survived the massacre but is receiving long-term treatment in a hospital in another city to which she — a destitute refugee, five months pregnant — cannot manage to travel. So she washes the clothing that soaked up her husband’s blood as he was left for dead in the street, and once that clothing is clean and dry she stuffs it in her pillowcase because she should be sharing her bed with her groom, like any other bride.

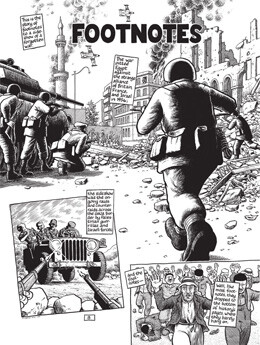

In his new book-length work of serial art journalism, Footnotes in Gaza, Joe Sacco seeks out that story and the recollections of the remaining Palestinian witnesses and survivors of the Rafah massacre — and the Khan Younis massacre that came days before it — whose experiences aren’t recorded in any government archives. The result of Sacco’s search is a powerful oral history — his research as detailed and meticulous as his crosshatched drawings, its 386 pages of sequential comic strip-style narration emotionally devastating. Fans of Palestine, the single-volume collection of the comic book series Sacco drew during his two-month trip to the country in the winter of 1991-1992, will not be disappointed.

What Sacco portrays in Footnotes is an ongoing, not compartmentalized or amputated history. The survivors and witnesses Sacco interviews and illustrates are still living out the occupation and its violence — as they have for decades. Indeed, some of his informants, hunched over their canes and their faces lined with grief and age, confuse traumatic events that happened during Israel’s conquest of Gaza in 1967 for what happened in 1956, peeling their trauma back like the noxious layers of an onion.

To illustrate how tightly this history is tied to the present, Sacco dedicates pages to the problems of the Palestinians he befriends as he carries out his research. One is on a United Nations refugee agency waiting list for new housing after the Israeli army destroyed the home that his family poured their savings into building. Another is a wanted resistance fighter living underground. Hollow-cheeked from fatigue, his existence is reduced to Gaza’s narrow, overcrowded alleyways while he enjoys little reward for his sacrifice or a semblance of a normal life.

A page from Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza.

In addition to excavating the history of those massacres, Footnotes in Gaza makes hauntingly clear that Israel’s policy of collective punishment or “deterrence” — on full display during the invasion of Lebanon in 2006 and last winter’s Gaza attacks — is nothing new. Sacco inks the hell that Palestinians were plunged into in April 1956 when the injuring of seven Israelis by Palestinian fighters was answered with the shelling of the bustling main street of Gaza City (followed by a second round of shelling after a crowd had formed). Approximately 50 Palestinian civilians were killed in those bombings. This chaotic scene of swirling smoke and civilians wide-eyed with terror is contrasted with the cool assessment of Israeli army Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan’s one-time adviser, Mordechai Bar-On, who rather clinically claims, “Dayan, I think, reacted almost spontaneously. I wouldn’t say irrationally.”

Here, Bar-On’s military armchair commentary is like a footnote to the Palestinians’ oral history, but usually men like him are the primary source for news copy — like The Times article from 1956. Surely they are the go-to sources for Sacco’s mainstream media reporter friends whom he (not unsympathetically) depicts as living the high life in West Jerusalem — chasing the new big story, getting their quotes from official sources, writing up their copy, and getting back to their expat partying lifestyle.

In Footnotes, those journalists’ breaking stories serve as a backdrop to the historical context. Sacco wants his readers to understand that a suicide bombing in Haifa, or the killing of US activist Rachel Corrie in Gaza — both of which occur during his field research — can only be understood within the context of the 1948 dispossession, the consequent Palestinian resistance, and the brutal way in which Israel has always attempted to stamp out Palestinian refugees’ efforts to return to their homeland.

Maureen Clare Murphy is Managing Editor of The Electronic Intifada.

Related Links