The Electronic Intifada 17 September 2013

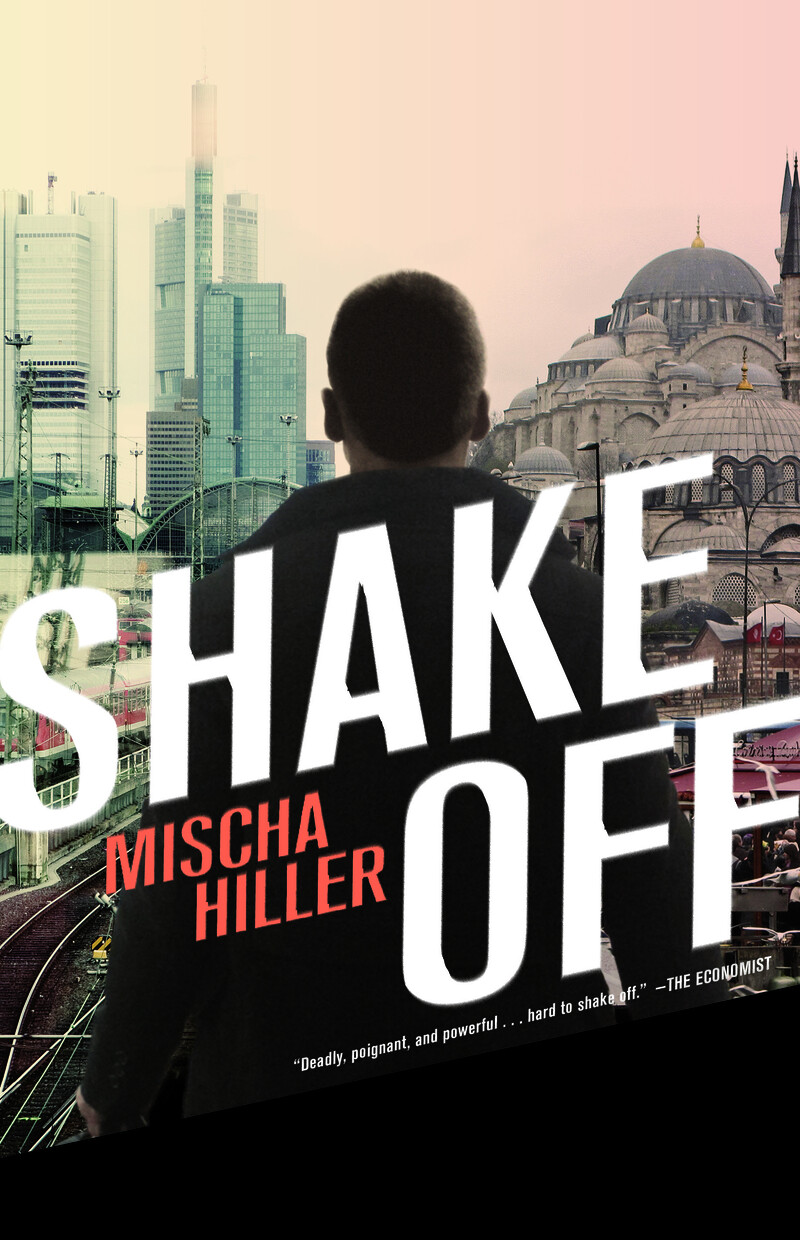

There are few works of fiction about Palestine or Palestinians that compare in quality, purity and control as those written by Mischa Hiller. Shake Off is the accomplished second novel of a writer who won a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for his equally haunting debut Sabra Zoo.

In both Sabra Zoo and Shake Off worlds of war, massacres and political espionage are conveyed through the first person narrative of young male protagonists. It is the sensitive portrayal of these endearingly honest, savvy characters, lumbered with internationally unwanted (and unrecognized) national identities, that embeds the reader’s emotional concern from the opening pages, giving Hiller a deft and rare ability to carry readers through the rough terrain of conflict.

It is also commendable that Hiller manages to achieve such a wide breadth of location, characters and political landscape while using the often limiting device of the first person.

The opening page of Shake Off explains its title — “Intifada/inte’fada/ noun. [Origin: Arabic intifada lit., a shaking off, der. of fada to shake off]” — but as with all good titles, the meaning here is multifold, shaking off the enemy, the past and one’s identity (assumed or otherwise). The novel is, unsurprisingly, set in 1989 during the first intifada; the protagonist, Michel, orphaned as a child in the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon, is an undercover operative for the Palestine Liberation Organization and the action moves between Beirut, London, Cambridge and Berlin.

Sex has never been anything other than a paid for, perfunctory event for Michel and he can only soothe out the horrors of his mind each night by using a combination of head rocking and heavy doses of codeine, until he meets his seductive student housemate, Helen. The horror of the past pursues Michel with a steady subtlety and drive throughout the novel: “They say that a personal tragedy fades over time, but that is just a lie to make you feel better. What happens is that it becomes suffused into your system, more integrated into the everyday fabric of your life. It is like homogenizing the cream into the milk, rather than it sitting at the top of the bottle: the cream is still there, you just can’t see it.”

Unadorned

Hiller’s style of writing is refreshingly sparse for a novel set in the Arab world, allowing the reader to breathe through the emotions of its characters rather than having them spelled out or embellished on their behalf. When the woman the protagonist fears he loves snaps at him, the young double agent looks down to see his shoes as though for the first time: “Your shoes should always match your clothes. The shoes had little perforations in the top; I had no idea what they were for. I had a strange awareness of myself, as if I was someone else waiting to use the phone, looking in, and hated what I saw; my shoes, my suit even my face.”

There is nothing sloppy in Hiller’s unadorned work. The plotting in this tight novel is intricately achieved, working on several levels at the same time. The spy thriller poses its own demands, many of which are only realized at the novel’s end as identities are unveiled and the mysteries of who knew what when unravel, throwing the reader into a deeper retrospective appreciation of the work.

Hiller’s knowledge of undercover operations and their training is similarly thorough and intriguingly reveals a world of espionage training of Palestinians rarely documented elsewhere and yet he is restrained in his use of his research. Hiller does not gratuitously drag the reader through his homework, but it has made him as a writer familiar enough with his subject matter to allow him to enter into the minds and voices of his characters with ease.

The voice of Michel is similarly trained and controlled; when describing a shooting in a European capital, the events unfold movement by movement, and the narrator’s voice maintains the tone of a trained operative with repressed emotion and heightened observational powers: “His right eye exploded in a red mess onto the inside of his glasses. I tried to hold him up as he collapsed across the woman on the ground. The man in leathers was now properly visible to me: he was holding an automatic with a silencer. I tried to identify the model.”

Many Palestinian writers or writers on Palestine have come unstuck in trying to maintain the balance between their artistic aspirations against the depiction of the all-too-ignored national narrative. Hiller’s work is essential in bringing recent Palestinian history and its unsung heroes alive stylishly and sexily (for both novels are infused with a taut sensual need of the protagonists for specific women) while writing with a moral and political responsibility that is mature and yet neither self-glorifying nor overly sentimental.

Selma Dabbagh is a British-Palestinian writer. Her debut novel is Out of It is published by Bloomsbury (2012). Her first radio play, The Brick, set in East Jerusalem, will be aired by BBC Radio 4 on 2 January 2014.