The Electronic Intifada 24 April 2015

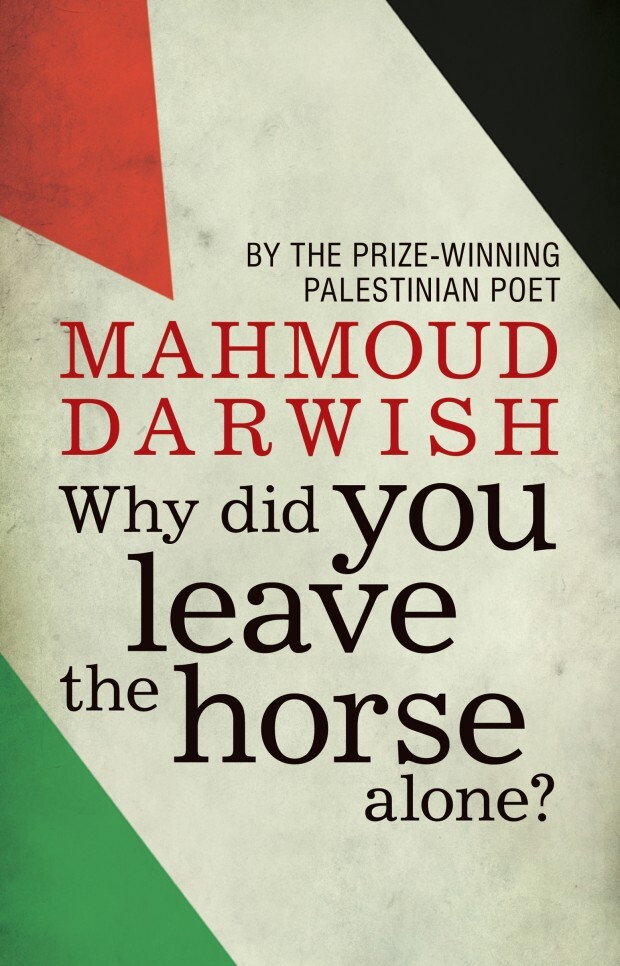

Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? by Mahmoud Darwish, translated by Mohammad Shaheen (Hesperus Press)

Mahmoud Darwish always denied that he spoke for or represented the Palestinian people, despite being the poet whose transcendent skill captured, for many, the sorrows of their situation. And yet, in his 1995 poem-cycle Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone, the resonances of his individual experiences do just that, evoking something much greater and more universal.

Darwish opens with “I See my Ghost Coming From Afar” — a poem which frames the collection, asserting the poet’s overview of the histories contained in the rest of the works. In a series of statements beginning with “I look at…” and culminating in “Like the balcony of a house, I look at whatever I will,” Darwish signals a kind of omniscience, laying claim to a knowledge of his own past which defies appropriation and distortion.

Nowhere is this more strongly expressed than in the first sequence of poems, set in Darwish’s native Galilee, recording a growing boy’s wanderings and interactions with his parents and the oppressive presence of British colonial troops: “My son, remember: here is where the British crucified/Your father on a prickly pear hedge for two nights,/But never did he confess.”

Despite this, there remains a sense of being rooted in the landscape — a familiar strand from Darwish’s earlier works. The poem continues: “The whole sky is ours from Damascus/To the lovely walls of Acre.”

The second sequence is titled “Abel’s Space,” evoking the Biblical story of Adam’s son, murdered by his brother in a killing which symbolizes the fratricidal violence of the Nakba, the ethnic cleansing of Palestine at the time of Israel’s establishment in 1948.

The origination of Arabs through Ismail, the brother of Isaac, is drawn from the scriptures of Judaism, Christianity and Islam alike. But in Darwish’s formulation, Ismail’s oud, the archetypal Arabic musical instrument in which “the Sumerian wedding is raised,” contrasts with the new, foreign guitar. The outcome, as Darwish sees it, is “merely two witnesses, two victims.”

Tinged with passion and grandeur

In the third section, Darwish evokes separation, distance and longing but, in a reflection of his own life story, tinges them with passion and grandeur. His mother is contrasted with beautiful foreign girls; the reader is reminded that the Palestinian rural traditions which are rooted in the land coexist with a history that is indebted to far-flung cultures, so that “I want both of you together, love and war… Two women who will never be reconciled…”

The emotion of the following sequences folds back in on itself, returning to inward reflection and imagery on a smaller scale — sparrows and butterflies, and the personal burdens of prison and separation.

Homer’s Helen of Troy becomes part of the everyday, in a meeting “on Tuesday/At three o’clock… In a street narrow as her sock.”

Lovers leave each other in sadness and chaos, and beauty and music always seem to exist alongside breakage and loss.

In the final sequence, we seem to meet a mature, sober, sometimes regretful Darwish. Moving from mythical and classical references he shifts to his literary companions — from the Arabic poet Imru al-Qais in the sixth century to Bertolt Brecht in the twentieth — and from love on a grand, sweeping scale to a more everyday scale: “And in order to dream I do not need/A large house.”

Cruelly perfect

In the closing poem of the book, Darwish shapes a scenario which could be that of the West Bank in which he lived his final years. “The enemy” drinks tea in “our hut,” rests his rifle on “Grandfather’s chair” and “strokes our cat’s fur” while “he constantly says to us: Don’t blame the victim! We ask him: Who is that?”

In images which are unusually direct by Darwish’s standards, but characteristically powerful, he evokes in cruelly perfect words the appalling intimacy of Israel’s occupation, the ways in which on the levels of both discourse and physical appropriation everything down to “our coffee cups” is stolen away.

If anything detracts from this edition of Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?, it is the translation. Although Mohammad Shaheen is an able translator, his approach is sometimes overly literal.

While, for instance, the glittering arcs of Fady Joudeh’s translations have sometimes been criticized for straying too far from the Arabic originals, at least his style captures the literally breathtaking experience of reading Darwish.

In Shaheen’s versions, the occasionally clunky English fails to convey the greatness of Darwish’s writing, the combination of technical cleverness and soaring imagery and metaphor which makes his work so special.

This raises an issue about the translation of Darwish’s poetry which goes beyond this single volume. At least a dozen different translators have issued collections of Darwish’s work in recent decades.

Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? has itself been translated at least once before, in a 2006 bilingual edition by Jeffrey Sacks.

All — or most — of those translators have brought their own unique touch to the notoriously difficult art of capturing the poetry of one language and trying to convey sense, meaning and feel into another, with all of the linguistic and cultural baggage that attends such a project.

But it does mean that readers, especially those in different parts of the English-speaking world, are subjected to a bewildering array of similar, often overlapping, editions. As well as the varying translations, these also diverge in, for instance, the extent to which they include context and background information — on Darwish, his works, the political and cultural environment in which the works were written.

Surely, given the stature of Mahmoud Darwish not only in the Arabic-speaking world but globally, and given the level of global interest in Palestine and its culture, there is a real need for a more coherent and serious approach to translating his work. A critical volume of complete works, properly contextualized and with a seriously considered translator, would be a major asset in conveying the greatness of Darwish to an international readership.

Sarah Irving is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone, a collection of contemporary Palestinian poetry in translation. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh.