The Electronic Intifada 5 February 2007

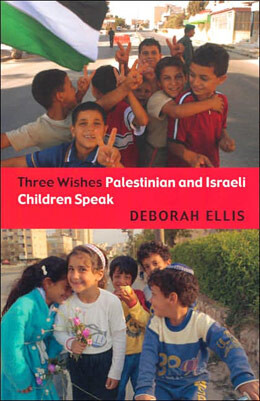

Three Wishes: Palestinians and Israeli Children Speak

Ellis provides a framework and a context that enables the reader to situate the interviews with the children. She briefly explains the history of the conflict and provides the arguments as seen by Israelis and by Palestinians. Both narratives are therefore provided. The reader will also understand what a Jewish settlement is, how some roads are for Jews only and how Palestinians are controlled by a system of roadblocks and checkpoints.

One hears the voices of Palestinian and Israeli children and one is able to enter into a world that is bound by fear, anxiety and sometimes despair. Yet one also sees glimmers of hope and possibilities of a better life.

What we learn by reading these accounts is at times shocking to the point where I think every Arab and Israeli politician should be required to read the book, if only to finally realize what kind of world they are creating for their children. We learn for instance that there is absolutely no contact between Palestinian and Israeli children. One fifteen-year-old Israeli youngster, a recent immigrant from Russia, says, “I know a little bit about the Palestinians from the news. It seems they all hate us, but I don’t know why. I have not met any yet. It is impossible for us to meet. We are separate people” (p. 23). An eleven-year-old Palestinian says, “I don’t know any Israeli children. I don’t want to know any. They hate me and I hate them” (p. 50). Merav, a thirteen-year-old Israeli who lives in a settlement (which means a place built for Jews only on confiscated Arab land in the heart of the occupied West Bank) has this to say: “I don’t know any Palestinian children. They are all around the outside of my settlement, but I don’t know any of them. I have no reason to meet them. They are dangerous and will shoot me if they get the chance. The Israeli army keeps them away from us” (p. 67-68).

Usually, the only Israelis that Palestinian children see are the soldiers. Here is a twelve-year-old Palestinian child speaking: “There are a lot of soldiers where I live. They watch us all the time. We can’t do anything without being watched by them. They carry guns, and they give me nightmares. We would like them to go away, but they don’t care about what we want” (p. 25).

It is interesting to note how heavily socialized Israeli children are: nearly all mention school field trips to the Yad Vashem holocaust museum, boy scout activities, one child mentions a visit to Poland “to see for ourselves what happened to the Jews during the war,” (p. 29) and army service. It is also quite interesting to see how propaganda themes and anti-Arab images filter down to children. Here is an example from an eighteen-year-old in a Jewish settlement north of Jerusalem: “We, the Israelis have been trying, but how much can we give? After all, this is our land. I wish all the Jews in the world would come to Israel, and that all the Palestinians would leave and go live in some other Arab country” (p. 76).

By contrast, Palestinian children do not seem to undergo such a thick process of socialization. They appear to be influenced more by the texts of everyday life, what they see around them. Here is an eighteen-year-old who lives in a refugee camp near Ramallah: “A lot of people die in this camp. The Israelis shoot missiles at us. Not long ago, a missile hit a car and killed a woman and her three children. Two other women were killed by a land mine. Lots of people die here” (p. 79). The boy has been in a wheelchair for the past few years, not because of any injury, but because “he was frightened by the soldiers a few years ago, he became unable to move his legs and one of his arms. He hasn’t walked since” (p. 79). To her credit, Deborah Ellis points out that many Palestinian children have suffered what we call post traumatic stress syndrome, a widespread phenomenon that has received little acknowledgment or attention. Those who live in refugee camps have suffered the most because that is where the Israeli army focuses its most intense assaults. The symptoms include listlessness, inability to concentrate, bedwetting, aggressive behavior, insomnia and nightmares.

Israeli children who have come into contact with Palestinian children tend to see things somewhat differently. Here is a fifteen-year-old who lives in Jerusalem: “I used to take an art class with Palestinian children. I was eleven years old. It was no big deal. They were just kids doing art, same as me. We didn’t fight because they were Palestinian and I am an Israeli. We were just kids doing art” (p. 96). This young man notes, “I don’t think we’ll ever get out of this situation unless we give the Palestinians their own state. It’s the only way to make peace. Everyone will have to give up a little of what they want in order to get some of what they want. We’re both here. Neither of us is going to go away” (p. 98).

Some of their wishes are touching indeed. Nearly all wish for the fighting to end. A fourteen-year-old Palestinian girl says, “I wish the fighting would end, so that we can just make music and have fun and not hate each other. Maybe we could even make music with the Israelis one day” (p. 62). One sixteen-year-old Israeli says: “My three wishes? I have just one. I want the war to end, so I can keep living in Israel and raise my children here” (p. 33).

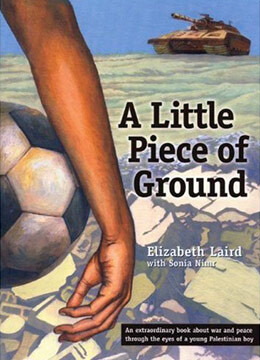

The book tells the story of the Aboudi family who live in Ramallah, their twelve year old son Karim and two of his friends, one of whom, Hopper, comes from a refugee camp near Ramallah and the other, Jodi, from a relatively well to do family. Karim daydreams about becoming a soccer star but has to contend with Israeli imposed curfews and checkpoints that restrict his freedom of movement. He sounds almost exactly like one of the teenagers in Deborah Ellis’s book who speaks about the threatening Israeli soldiers whose rules of engagement consider a twelve-year-old kid throwing rocks at them a legitimate target for killing. His father is humiliated in front of him by Israeli soldiers at a checkpoint while the family is traveling by car to spend a couple of days in their own ancestral village near Ramallah. The family and the relatives are abused and threatened by nearby Jewish settlers who live on confiscated Arab land as they try to harvest their olives, much as their ancestors have done for many generations. For these Jewish settlers, many of whom originate from the U.S., the land belongs to the Jewish people and the Palestinians who are said to contaminate it must therefore go.

Karim and his friend Hopper decide to reclaim a bulldozed lot and turn it into a football field. They also establish a secret den as an after school hideout. This effort to reclaim a little piece of ground eventually brings them face to face with Israeli tanks and a near fatal adventure that takes the reader directly to the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian confrontation. Karim is shot in the leg as he runs away from the Israeli soldiers but he survives. At the end of the story, the author narrates, “He’d go back soon, when his leg was better, and he’d start again, he and Hopper, and they’d bring in the other boys, and make the place theirs again, and play soccer, and play, and play” (p. 216).

Elizabeth Laird captures the nuances of the place so well that one forgets that the author is actually a foreigner writing about a Palestinian story. The interaction within the Aboudi family reveals a society where the family plays a crucial role in people’s lives, offering unconditional and loving support to all members. This may well be one of the main sources of strength that has allowed Palestinian society to persist in the face of Israel’s fiercest attacks against it. At one point, Hassan Aboudi, the father, who had suffered humiliation at the hands of the soldiers, sits silently at the family meal and then says, “Endurance. That’s what takes courage. Decency among ourselves. That’s where we must be strong. When they steal from us and try to humiliate us, the real shame is on themselves” (p. 65).

The book captures the effects of the Israeli invasion on schools and education. Several schools were vandalized by the Israeli soldiers and the Palestinian Ministry of Education was ransacked and its computers were smashed causing major loss in files and data sets. In the story, children are unable to concentrate; they were “edgy and restless”; they hear a big explosion outside their school and the frustrated teacher resorts to physical punishment to try to control them.

Laird also captures rather well the feelings of anxiety and loss as Karim’s best friend Jodi tells him that he and his parents have decided to leave the country. In those years hundreds of middle income families and professionals decided to leave because of their worries about their children’s welfare and safety. A closely knit society was being torn asunder as it had been twice before, in June 1967 and in April-May 1948.

A Little Piece of Ground is a metaphor for Palestinians who are simply asking the world to recognize their right to a tiny place where they can live freely and breathe some fresh air. It is also a story of their endurance and their refusal to bow down to superior and rapacious power.

Haymarket Books dedicates the book to the memory of Rachel Corrie, the young American peace activist who was crushed to death by an Israeli bulldozer. To her credit, Lynne Reid Banks offers a brief blurb on this book and says the following: “This story of how it feels to be under the heel of an occupier and how it affects day-to-day life is an oddly homely one. We get to care about this boy and his family and, yes, to loathe their oppressors — and I say that as one who lived in Israel for years and has written the story of terrorism in that area for children from the Jewish side … I know it is a good book and needs to be read by others like me.”

These brave authors of children’s books have had to deal with the thorny issues surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Although some of these books elicited near-hysterical outrage from hard-core pro-Israeli groups, it is, nonetheless, interesting to note that hundreds of thousands of copies of these various books have sold and continue to sell throughout the world and a number of these authors have gone on to win some important literary prizes. This means that the traditional hold that pro-Israeli groups have had, always exaggerated in my opinion, that resulted in the reluctance of known publishing houses to venture into this area has finally begun to recede.

We now have a number of well-written books that offer a rich and highly textured portrait of children’s lives in times of conflict. More importantly, we now have, for the first time, portraits of Palestinian children as normal human beings engaged in the daily struggle for survival, children with hopes and fears, hates and loves, just like the rest of the world’s children. This is quite remarkable because the Palestinian, as a human being, still does not exist. His or her identity continues to be submerged under various labels — he is a terrorist, or a religious fanatic, a hater of Jews, a moderate or an extremist. Palestinian casualties are usually just numbers, while Israeli casualties are humans with a life story. We are told their age, where they come from, who their friends are, who their parents are, what their hopes were and so on. It is therefore significant that, for the first time, we can see Palestinian children as normal human beings.

The generalized political discourse on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict often obscures the tragic toll the conflict takes on innocent civilians. These books highlight this human dimension and they do it well. In the process, they reveal to us the incredibly huge and tragic cost of this ongoing conflict and the urgent need for its resolution.

Fouad Moughrabi is Professor and Head of the Department of Political Science at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He is also Director of the Qattan Center for Educational Research and Development, Ramallah, Palestine.

Related Links