The Electronic Intifada 5 February 2007

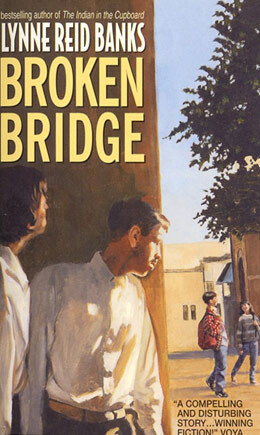

For a number of years, my twelve-year-old son Raja has been attending a good magnet school in Chattanooga, Tennessee. As a Palestinian child who had lived for three years during Israel’s most recent reinvasion of Palestinian cities, he has seen his share of tanks, helicopter gun ships and F-16 aircraft blasting missiles into populated urban areas of the West Bank, killing lots of innocent civilians. Back in Tennessee, he was sometimes asked to sing songs in Hebrew to celebrate Yom Kippur; he was given assignments dealing with the Holocaust; and he was told by one teacher that his impressions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are simply in his head. It was, therefore, not surprising at all for him to come home one day with a copy of Lynne Reid Banks’ novel Broken Bridge (1996), a sequel to an earlier book, One More River (1973) that she published about life on an Israeli kibbutz.

My son’s social science teacher told me that she was looking for a “balanced” novel. She acknowledged that she was delving into a rather controversial area. At the same time, like most American school teachers, she admits to a lack of the necessary historical knowledge that would enable her to talk about the context of the novel.

Controversies about the power of school textbooks in shaping students’ consciousness and attitudes have raged for some time. In a previous essay, I showed how the charges of incitement leveled by extremist pro-Israeli groups and some of their powerful American supporters against Palestinian textbooks are in fact fraudulent. Numerous other studies confirmed my findings. By contrast, there is much research by Israeli scholars suggesting that Israeli school textbooks contain a great deal of anti-Arab stereotyping.

These charges and countercharges, however, focus on textbooks which are the core of the formal school curriculum. What is even more important and perhaps even more nefarious is the attempt to sneak the same stereotyping and negative portrayals through what we call the “hidden curriculum”. This includes school activities such as the ones mentioned above and extra reading materials such as Broken Bridge as well as varying interpretations of texts offered by teachers who have their own specific agendas.

I write this on the day that my family and I attended the bar mitzvah of my son’s classmate and friend Aaron Steinberg. I was deeply touched when Aaron spoke so eloquently about the need for Israeli-Palestinian peace and proudly announced that he will donate half of the money he will receive as a gift to the Seeds of Peace Program which brings young Palestinian and Israeli youth together in order to promote coexistence.

Obviously, my son and his seventh grade classmates are beginning to think about these complex issues and some of them do so with some emotion, for one reason or another. The question is: do we have them read books that reinforce prevailing stereotypes and nasty media frames or do we try to show them another way. There is far too much stereotyping and dehumanizing that goes on in the public discourse about the Middle East in the media and popular culture. Our task is not to reinforce it but to challenge it. Luckily, there are other books and other ways that can be used to promote peace and coexistence

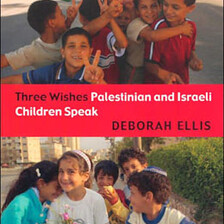

Therefore, I decided to read Broken Bridge carefully and to write my own reactions to it. I concluded that, although it is well written, it is, nonetheless, not a good way to introduce the issues to a seventh grade class. I outlined the main reasons for this and then began to look for better alternatives. I found an excellent book by the Canadian author Deborah Ellis entitled Three Wishes: Palestinian and Israeli Children Speak and another by Elizabeth Laird entitled A Little Piece of Ground that chronicles the life of a Palestinian teenager during the most recent Palestinian Intifada and the Israeli assault on Palestinian towns. What follows is a review essay of all three books.

The core of the book as well as its starting point is a rather shocking act of violence perpetrated against a teenager that most Western readers will immediately identify with. While the Israeli Jewish characters are well developed to the point where we can even empathize with them, the Arab characters are nebulous, distant and threatening.

The Arab first appears in Broken Bridge on p. 21 as a taxi driver. The Jewish teenager is warned: “ ‘If it’s an Arab driver, don’t get in!’/ ‘Why?’/ ‘Dangerous.’/ ‘More than thorn?’” Soon thereafter the Arab appears as a murderer. On p. 26, news comes on the radio that a child has been stabbed in the street in a place called Gilo.

The feeling of a pervasive danger that the Arab represents, followed immediately by the stabbing of a Jewish teenager, sets the tone for the entire story. Furthermore, the event happens in Gilo, referred to in the story as “our district,” a suburb of Jerusalem. Just how many American school teachers would know that Gilo is, in fact, a Jewish settlement, illegal according to international law, because it is built on confiscated Palestinian land in full view of the Arab village whose inhabitants still carry the deeds to their stolen land.

Mustapha, one of the main Arab characters in the story talks his nephew into becoming a “fighter.” They both finally embark on an operation during which Feisal, the nephew, kills the Jewish teenager who was visiting from Canada. Mustapha, however, mysteriously ends up sparing the life of the boy’s cousin, a girl who was walking with him. The other Arab characters include Ali who tries to save his job at a Jewish restaurant in Jerusalem by reporting to the Israelis about his neighbors in the nearby village and Mustapha’s brother-in-law who becomes a collaborator and finally betrays him to the authorities.

The author engages in a bit of hyperbole describing the training that Mustapha had received in order to become a terrorist: “When Mustapha had been sent abroad for training, he was made, among other things, to bite the heads off live chickens to toughen him up. Not that he’d needed it — not after what he’s been through. Each time he had told himself that the chicken was the Jew who had interrogated him … But Feisal was not so strong and tough as Mustapha thought he needed to be” (p. 128). I have never heard of any such bizarre rituals among Palestinians and I seriously doubt that such things ever occurred. However, attributing such monstrous behavior to Palestinians is quite common in Israel. Sadly, it reminds us of the bizarre rituals attributed to Jews by anti-Semites.

In a rather odd twist, the author informs us that Mustapha is said to be originally from a small village in Jordan, just across the border, and therefore not a native but an import or an intruder. We are told that his father had brought him to the West Bank after the June 1967 war, leaving his mother and sisters behind, in order to help fight the Jews. This gives credence to an Israeli-generated myth that the native Palestinians are not unhappy with their lot and prefer to live under Israeli control if it weren’t for the troublemakers who sneak in from the neighboring Arab countries and who are determined to drive the Jews into the sea.

In contrast the Jewish characters in the story are playful, cultured and normal human beings, while the Arabs appear as non-descript, without a history and a normal existence. The author, who is impressed with Arabic food, very much like most Israelis who also like it to the point where they even appropriated it as their own (we now have Israeli hummus and falafel, for example), nonetheless feels compelled to criticize the excess that Arabs go through in preparing it. She does describe the anxiety that Feisal undergoes before he commits his violent act. Yet, to a large extent, there is nothing in any of the Arab characters that would make one empathize with them in any way. They remain dark and shadowy figures, always lurking in alleyways, waiting to pounce on some unsuspecting Jew.

The author tries to appear balanced in her narrative. But this balance is rather odd because it is not a balance between the Israeli and the Palestinian narratives. There is very little here about the Palestinian narrative. We are offered scattered tidbits here and there about how bad the occupation is. We are told that fanatical religious Jewish settlers terrorize Arab villagers (she fails to mention that they do so even as the Israeli army often simply looks on). She provides a passing reference to the 300-plus Palestinian villages razed to the ground by the Israelis in 1948 in order to make sure the Arab refugees will never be able to return. The reader will therefore know very little about the Palestinians, who they are and why they sometimes behave the way they do.

What appears as “balance” in the book emerges because the author captures rather well the debate within Israel itself between those who hold the Palestinian Arabs with racist contempt and those who argue that the Israeli occupation of Arab lands and the harsh treatment of Palestinians by their Israeli occupiers may account for Palestinian acts of violence against the Jews.

It is precisely the appearance of balance that makes uninitiated American readers think this is a book that tries to promote peace. This works mainly because most American readers lack the necessary historical knowledge that would provide the needed context for the stories. And herein lies the key problem with choosing a book like this as an introduction to this conflict. Without some knowledge of the context, of the history and of the nuances of the place, one ends up simply adding insult to injury and reinforcing pre-existing stereotypes that dehumanize people. In the end, the media frame of the Arab as “terrorist” is given a substantial boost and is reinforced in the minds of Americans children.

In essence, the book frames the issues almost solely in terms of conflict and violence — in this case, Palestinian violence against Jews therefore making the Arabs the perpetrators and the Jews the victims. It provides nothing about the richness of the Palestinian narrative and its complexity. After reading the book, one understands why Israelis engage in acts of violence against Arabs and may even empathize with them but one does not understand the circumstances that drive some Palestinians to engage in violence. More importantly, one does not see any glimmer of hope that this cycle of violence will ever come to an end, as if it really were an immemorial kind of conflict.

The story is fundamentally the chronicle of a moral debate. But, because only Israeli Jews are presented as human beings, the debate occurs basically among them. In principle, this is fine except that it is really an artificial kind of debate. What the author does not tell us is that those who hold Arabs with racist contempt are in fact the majority among Israeli Jews, as confirmed over and over again by Israeli public opinion surveys. By contrast, those who argue for a humane approach to dealing with the Palestinian Arabs are in reality a very tiny minority whose voice is marginalized in Israeli society. In the end, the impression that there is a vigorous and healthy moral debate in Israel is simply either a fraud or just an example of wishful thinking among well-meaning writers and intellectuals that serves to present Israel as a normal, civilized, and democratic society where such debates are said to occur.