Electronic Lebanon 19 January 2010

NAHR AL-BARED, Lebanon (IPS) - Recent inter-factional clashes in Lebanon’s Ein al-Hilwe refugee camp once more illustrated the fragile security situation in some of its Palestinian camps. Lebanese plans to take over security within the camps are rejected by the Palestinians.

The new year had hardly begun when the sounds of gunfire and rocket-propelled grenades rocked Ein al-Hilwe camp on the outskirts of the Lebanese coastal city Sidon. The most recent clash broke out when fighters belonging to the militant Islamist group Jund al-Sham attacked an office of the mainstream Fatah movement within the camp. The fierce fighting was contained and eventually stopped when the camp’s security committee intervened.

Ein al-Hilwe and other refugee camps are home to various Palestinian nationalist groups, but also host different Islamist forces that the Lebanese government considers a threat to the state’s security and stability. In 2007, one of those groups called Fatah al-Islam engaged the Lebanese army in a 15-week battle in Nahr al-Bared, the country’s most northern Palestinian refugee camp. Nahr al-Bared was reduced to rubble, and 30,000 fled.

Lebanon hosts around 250,000 Palestinian refugees, many living in 12 officially recognized refugee camps. They have no education or employment rights comparable to the Lebanese. The Cairo Agreement of 1969 put the camps under control of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and banned Lebanese security forces from entering.

Although the Lebanese government withdrew from the Cairo Agreement in the late 1980s and theoretically reclaimed its rule over the camps, the state has refrained from exercising its authority. Politically, the camps have been ruled by popular committees, while security committees have been serving as an internal police force.

When in 2006 Fatah al-Islam trickled into Nahr al-Bared however, the camp only had a weak popular committee and no functioning security committee. The Palestinian parties were divided, and consequently failed to push the well-armed Islamist group out of the camp, effectively allowing it to take over.

At the 2008 international donor conference for the recovery and reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared, the Lebanese government declared that once rebuilt the camp would “not return to the environmental, social and political status quo ante that facilitated its takeover by terrorists,” but be put under its authority.

It announced that the rule of law would be enforced in the camp by community and proximity policing through the Internal Security Forces (ISF). Pointing to the destroyed camp as an experimental ground, the government stressed that success in Nahr al-Bared would promote a security model for other Palestinian refugee camps.

In October 2009, a senior ISF delegation toured the United States to study community policing. The visit was part of a program sponsored by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Narcotics and Law Enforcement. Assistance under the program includes construction of an ISF police station, and equipment such as patrol vehicles and duty gear. Since 2006, the US government has provided Lebanon with more than half a billion dollars in security assistance.

Community policing is an approach to police work in specific, well-defined areas. In theory, it builds on mutually beneficial ties between police and community members, and emphasizes community partnership and problem solving. The community police benefits from expertise and resources existing within communities.

Marwan Abdulal, the PLO’s official in charge of the reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared, doesn’t like the idea of implementing the concept in the camps. “It doesn’t take into account the peculiarity of Lebanon and the Palestinians’ presence in Lebanon,” he says. If Lebanese law remained discriminatory, and is enforced, he said the experiment is doomed to fail.

“The concept is fashionable. The word ‘community’ sells,” says Amr Saededine, an independent journalist. He says community policing is about getting people to spy on one another, and report to the security service. Ghassan Abdallah, director general of the Palestinian Human Rights Organization, points at polls indicating that a large majority of the refugees do not trust the Lebanese security forces, and object to them controlling the camps.

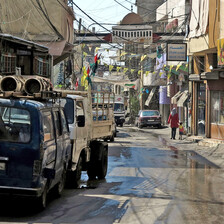

Beirut and the government palace are far from the ruins, rubble and muddy streets of Nahr al-Bared. Here, the reality is different. More than two years after the war, about 20,000 refugees have returned to the outskirts of the camp, which is still surrounded by army posts, barbed wire and five checkpoints. Access for Palestinians and foreigners is only permitted with extra permits issued by the mukhabarat, the Lebanese army’s intelligence service.

The mukhabarat constantly patrol the streets and have been recruiting scores of new informants. An atmosphere of fear has spread across Nahr al-Bared. Residents avoid talking about sensitive issues such as the Lebanese state or its security apparatus in the presence of individuals they don’t know.

Women especially are recruited. Informants mostly get paid in phone cards. Others receive practical benefits like easier access to the camp. A social worker who doesn’t want to be identified says, “It’s as if they planted a virus within society, which is difficult to get rid of.” Living under military rule and having no security committee, the camp’s residents are unable to clamp down on the informants.

The army’s control over daily life “makes people explode at some point,” says Sakher Shaar, a hairdresser in Nahr al-Bared’s main street. “Why do they treat us this way? Why don’t they treat us like the residents of the surrounding Lebanese communities? We’re not their enemies.” Many refugees remember the Palestinian revolution in the late 1960s which was a reaction to the humiliating rule of the army’s intelligence branch known as the “deuxieme bureau.” The uprising started in Nahr al-Bared.

A few months ago, the ISF set up a police post at the northern edge of Nahr al-Bared. The PLO’s Marwan Abdulal welcomes steps to transform the military zone into a civilian area. But he says “the problem is that when the ISF entered, the army remained present.” Indeed, the ISF’s role in the camp is currently almost zero, while the army keeps control, intimidating and arresting people.

The Lebanese ministry of interior seems unsure how to let the ISF enforce the law. “They would have to imprison the whole camp,” says Saededine. “Palestinians are forbidden to own property, to work in many professions, to open a shop, to found a civil society organization …” Serious law enforcement in the camps by the ISF would ultimately require a fundamental change in Lebanon’s discriminating law.

The issue at stake in Nahr al-Bared is not just its future security arrangements, but its governance in general. The PLO has realized the need for a reform of the popular committee. Abdulal suggests a civilian body similar to a municipality, consisting of the parties as well as representatives of the civil society.

On internal security, the PLO suggests self-governance to counter the government’s intention to introduce community policing. Pointing to the successful model practiced in Syria, Abdulal says there should be a Palestinian police force attached to the popular committee and coordinating with the ISF, which should remain outside the camp.

A similar model has informally been practiced in most Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Their security committees have been coordinating with the Lebanese authorities, and have repeatedly handed over suspects to the state. Saededine argues that if there was a serious attempt to reorganize camp governance and security, one would have to look at how society itself used to solve its problems, “but dropping the Anglo-Saxon concept of community policing by parachutes on the camp is irrational.”

After some Lebanese media recently reported on a stun-grenade attack in Rashidieh camp in Lebanon’s south, Sultan Abu al-Aynayn, a Fatah official, accused them of bloating up this personal act and depicting it as having political and security dimensions. He argued that this steady focus on Palestinians as a security problem obscures their demands for civil and social rights.

Abdulal insists that it is impossible to have Lebanese state security without human security for Palestinians. “There has to be a general feeling of security among Palestinians, in the political, economic, social and cultural sense.”

In Lebanon, Palestinians are still seen solely through security eyes. In Nahr al-Bared, the government has allowed the army to play a major role in the reconstruction project. It hasn’t shown will to revise its treatment of Palestinians and finally — after more than 60 years of their presence — abolish the legal discrimination against them. Current developments in the laboratory called Nahr al-Bared point to a one-sided imposition of direct rule on Palestinians rather than a “mutually beneficial partnership” between them and their hosts.

All rights reserved, IPS — Inter Press Service (2010). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.