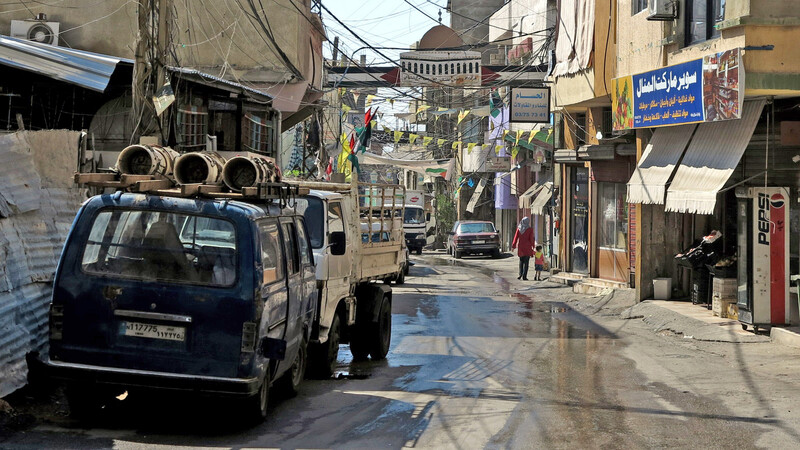

The Electronic Intifada Burj al-Shemali refugee camp 9 January 2015

Palestinian refugees from Syria are able to stay out of reach of the Lebanese authorities in camps like Burj al-Shemali.

Abu Ahmad has his daily routines. One is walking from his tiny flat in south Lebanon’s Burj al-Shemali refugee camp to al-Houla, a local community center. There he drinks coffee and chats with friends.

Abu Ahmad looks tired, even though there is not much to do these days. “I can’t find work here,” he complained. Back in Syria, in Damascus’ Yarmouk refugee camp, things were different. There, Abu Ahmad was a carpenter, happy with his life and busy with his work.

That dramatically changed when the war in Syria spread to Yarmouk. The camp, once home to 160,000 Syrians and Palestinians, has been under siege for two years now. For Abu Ahmad, the situation soon became unbearable, so he fled the country and sought shelter with his wife’s relatives in Burj al-Shemali.

He soon found himself trapped with no work and no hope for a speedy return to Yarmouk — and a volatile residency permit status.

Palestinians in Syria

The Palestinian refugee camps in Syria were established in the wake of the 1948 Nakba in Palestine — the massive act of ethnic cleansing in which Zionist militias drove out half of the Palestinian population by force.

The ongoing war in Syria has forced nearly 80,000 Palestinian refugees there to flee to neighboring countries — refugees all over again. An estimated 560,000 Palestinian refugees lived in Syria before the war.

While nearly 15,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria are recorded with UNRWA, the United Nations agency for Palestine refugees, in Jordan, approximately 44,000 have so far reported to UNRWA’s field office in Lebanon, many of them fleeing the siege of Yarmouk.

Palestinian refugees from Syria are scattered all over Lebanon and often live with family members. According to UNRWA, 7,000 live in and around Tripoli, 7,300 in the Beqaa valley, 7,500 in Beirut, 14,200 in and around Sidon and 8,000 in Tyre and its surroundings (including Burj al-Shemali camp).

As Palestinians, they are not allowed to register with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, unlike Syrians who have fled their country. Instead, families receive $100 per month for housing and $30 per person each month for food and clothes from UNRWA.

Rivals on the labor market

Shadi Aboud, another Palestinian refugee fleeing Syria, found work in a telephone shop in Nahr al-Bared camp in the north of Lebanon.

Nahr al-Bared hasn’t recovered from a war in 2007 that destroyed the whole camp. It still awaits reconstruction and 15,000 of its displaced residents are waiting to return. Yet many Palestinians from Syria have ended up there. Some of them now live in the temporary housing units abandoned by local Palestinians who have since relocated to newly built homes or rented accommodation.

“Basically, a takeover happened,” said Zizette Darkazally, chief communications officer in UNRWA’s Beirut office. She asked: “Given the circumstances: What else than letting them stay should we do?”

Shadi Aboud says his relations with the local Palestinians aren’t good. “They accuse us of taking their jobs,” he said.

The economic situation for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon was already dismal before the war in Syria. But workers like Nahr al-Bared resident Muhammad Eshtawi say that work conditions are worsening as a direct result of the refugee crisis.

“Now, I’ve finally found work, but the wage is low and my boss recently started to delay payments,” Eshtawi said. His Lebanese employer at a Tripoli construction company told him that if he doesn’t accept the conditions, he would simply employ Syrians in his place.

The burdens on Palestinian refugees from Syria are not limited to employment.

Shadi Aboud came to Lebanon almost two years ago and spent nearly a year in Beirut before relocating to Nahr al-Bared. Aboud had to renew his visa every three months. His last visa has just expired, but he says he won’t go to the General Security office to ask for renewal again.

“I’m afraid of being arrested and deported,” he said.

His fear is well-based. In summer 2013, the Lebanese government began to arbitrarily deny Palestinians from Syria entry to Lebanon. In May 2014, forty Palestinians were deported from Lebanon to Syria; the government claimed they had forged visas from third countries. Lebanon then introduced further entry restrictions on Palestinians fleeing Syria.

Dalia Aranki, an aid worker with the Norwegian Refugee Council, said: “For them, the border has effectively been closed since May 2014.”

Restrictions

Those already present in Lebanon are also facing further restrictions.

Before May, they could renew their three-months residency visas up to four times, then pay $200 and stay in Lebanon for another year. But many refugees were unable to pay the fee. And according to a recent Amnesty International report, since May, Lebanese authorities have refused to review visas for Palestinian refugees from Syria, without giving clear reasons as to why.

At the end of May, the General Security office had called on undocumented Palestinians in Lebanon to resolve their status by 22 June. Amnesty reported that some Palestinians who went to regularize their status before that deadline were instead given deportation orders.

In September, the General Security office again asked Palestinians from Syria to regularize their stay. The General Security office promised a free one-time residency visa, valid for three months.

“We don’t automatically encourage Palestinians to approach the General Security office without first ensuring they are able to make their own decision based on information and advice relevant to their respective cases,” said the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Dalia Aranki. She cited various bureaucratic hurdles, as well as the risk of detention at the General Security office.

From field work her organization has learned that if the requirements for regularization are fulfilled, three-month visas are generally granted. “The practice differs from one regional General Security office to another in terms of application of these new rules, though,” she said.

Afraid to leave

But what will happen once all these three-month permits expire?

The Lebanese authorities did not reply to a request for comment. Amnesty International, UNRWA and the Norwegian Refugee Council have no clear information on the issue.

“As we understand it, after the three-months stay, the Palestinian refugees from Syria will not be able to renew the residency visa and are likely to be unable to re-enter Lebanon, if they leave the country temporarily,” said Aranki.

“Based on a recent Council of Ministers decision, it seems that Lebanon is planning to set up mechanisms to reduce the entry of refugees, encourage refugees in Lebanon to return to Syria, try to establish camps there and enforce Lebanese laws pertaining to legal entry and stay and employment,” she explained.

Lebanon is close to making illegal even those Palestinian refugees from Syria that still have a valid residency visa. This means severe restrictions on the refugees’ freedom of movement, and they live in constant fear of arrest. Families are torn apart, as relatives cannot follow to join their loved ones in Lebanon.

Without legal status, Palestinians from Syria are unable to register births, deaths, marriages or divorces, access social services or obtain work permits. Even cash assistance is difficult: UNRWA transfers credit on cash cards, but there are no cash machines in the camps. Many Palestinians are afraid to even leave the camp to withdraw money.

“All of this forces the already vulnerable Palestinian population to take life-threatening risks, such as attempting to escape by boat on the Mediterranean, often with tragic consequences,” warned UNRWA spokesperson Chris Gunness.

Shadi Aboud and Abu Ahmad are not considering such a dangerous trip to Europe. Abu Ahmad is thinking of returning to war-torn Syria. Aboud has decided to stay in Nahr al-Bared for as long as possible and not leave the camp.

“Nahr al-Bared will be my open-air prison for the next few years,” he said quietly.

The names of Palestinian refugees from Syria have been changed for anonymity.

Ray Smith is a freelance journalist and has been an activist with the anarchist media collective a-films, which documented post-war developments in Nahr al-Bared from 2007 to 2010.