The Electronic Intifada Nablus 26 April 2011

Few visitors make it to the city of Nablus in the occupied West Bank

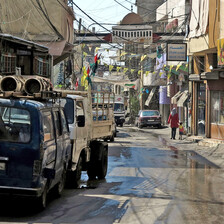

NABLUS, occupied West Bank (IPS) - Palestine experiences a boom in tourism, as herds of tourists storm the cities of Jerusalem, Jericho and Bethlehem. Meanwhile, the West Bank city of Nablus, rich in historic and religious sites, hardly attracts visitors.

“It’s an ancient city with a magnificent old town. It’s home to Jacob’s Well, the Samaritans and Sabastiya,” Salem Hantoli, manager of Nablus’ al-Yasmeen hotel, praises the various tourist attractions of Nablus, a city with 126,000 inhabitants in the northern West Bank. Al-Yasmeen, the second largest of Nablus’ four hotels, has 45 beds and 16 employees.

“Before the second intifada, our city used to be a major destination for religious tourism,” recalls Abdelafo S. Aker, public relations officer at Nablus’ municipality, adding that after the uprising, the siege and the closures, tourists have become rare in Nablus.

In 2009, only 7,170 hotel guests were counted in the whole Nablus governorate as compared to 451,840 in the occupied West Bank as a whole, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). For 2010, figures aren’t available yet.

Hotel manager Hantoli says that in 2008 things started to improve. “The year 2009 was even better, and 2010 was a boom.” Al-Yasmeen’s occupancy rates and revenue have reached new heights.

The hotel’s improving performance has to be considered in the light of the extreme slump during the intifada, however. “For at least five years, our occupancy rate was no more than 10 to 15 percent,” the hotel manager remembers. Even now, 80 percent of his guests belong to the alternative tourism sector, visitors with political interests. “Lately, but very slowly, we start to have people coming only for tourism.”

A contributing factor has been the easing of entry restrictions to Nablus since 2009. The city has been under strict closure for seven years and the Israeli army often denied foreigners passage through the checkpoints surrounding the city. “The slight increase in tourism is largely domestic though, it’s visitors from the West Bank and Israel,” says municipality officer Aker. In terms of international tourism, no big shift could be noticed.

Aker points at Israeli measures as the main obstacle to attracting more international tourists. “When at Ben Gurion airport [near Tel Aviv] you tell them you’re planning to visit Nablus, they’ll recommend you not going there because the city ‘isn’t safe.’ And surely they’ll make it harder for you to actually enter Israel,” says Aker.

During the intifada, Nablus and its three refugee camps were strongholds of armed resistance to Israeli occupation. Clashes, massive Israeli army raids, targeted killings and long curfews were part of everyday life. Israeli propaganda further contributed to the city’s image as a chaotic and dangerous place.

In Nablus, efforts are under way to change the city’s bad reputation. In 2007, the Palestinian Authority (PA) began to deploy police forces. Armed resistance has vanished and Israeli raids have become less frequent. They usually take place after midnight and are coordinated with the PA. Nablus representative Aker says that the much improved law enforcement has led to stability. “There’s no reason any more not to visit Nablus,” he concludes.

Yet local hotels are facing another problem. While in all other parts of Palestine, hotel guests stay for an average of two nights, in the northern West Bank they do so for less than 1.5 nights. Tour operators usually bring visitors only at daytime, while they spend their nights in Israeli hotels. Hantoli says that it’s also the operators’ responsibility to better link Palestinian sites. “Unfortunately, most of them still solely focus on Jerusalem, Jericho and Bethlehem,” he regrets.

Nablus lacks a competitive tourist infrastructure. “You can’t just jump to tourism,” PR officer Aker says. “We lack hotels, restaurants and experienced staff,” he tells. Attracting investment, however, depends on stability. Even though things have calmed down, military raids could still occur and at any point, closure may be imposed and access to Nablus be interrupted. The Israeli army remains a factor of uncertainty.

Huge potential is seen in the reconstruction and renovation of Nablus’s historic old town, likely the city’s main attraction. During the April 2002 “Battle of Nablus” and several other big Israeli army invasions, the old city has suffered heavy damage. Several mosques, churches and traditional olive oil soap factories such as the Kanaan and the Nabulsi factory were totally destroyed, while other sites such as the Ottoman-era Turkish bathhouse “Hammam al-Shifa” and the massive Abdelhadi Palace were severely damaged.

“By developing and renovating the old town, there’d be even more reason for tourists to actually spend more than just a few hours in the city,” explains Salem Hantoli at al-Yasmeen Hotel. The municipality along with Palestinian and international partners is working on restoring some sites and alleys in the old town. Renovation work is noticeable, but remains quite scattered.

“Our financial resources are very limited in comparison to the needs on the ground,” says the municipality’s representative Abdelafo S. Aker. The immense destruction of private property left hundreds of the old town’s 20,000 residents homeless. Sheltering and assisting them became a priority, while the protection of cultural heritage had to wait. “Also, infrastructure projects such as water, sewage or electricity have been our immediate priorities,” explains Aker.

In the heart of the old town, Naseer Arafat directs a nongovernmental organization called “Civil Society of Nablus Governorate.” “We used to pay the rent of people whose houses were destroyed or uninhabitable,” says Arafat. Nowadays, the organization is busy assisting people in renovating and rebuilding their private homes under the aspect of humanitarian aid.

During the interview residents pop in, listing up their needs and asking for money. “We’re not fast enough, because we’re lacking money,” Arafat regrets. “Still more than 200 houses are in need of reconstruction.”

Not far from Arafat’s office lies the huge Tuqan palace. During the eighteenth century, the Tuqan clan nearly controlled all of Nablus and its hinterland. The palace is mostly neglected and its back garden now looks like a jungle. Obviously, restoration efforts would have to be a massive undertaking.

Members of the Tuqan family say it’s beyond their financial scope. As time passed, the clan’s wealth trickled down through several generations and dispersed. Goats are now grazing where once Nablus’s powerful elite ruled.

All rights reserved, IPS — Inter Press Service (2011). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.