Youth from Bilin watch from atop a home as Palestinian and international protestors are shot at with teargas by Israeli soldiers. (Tess Scheflan/ActiveStills)

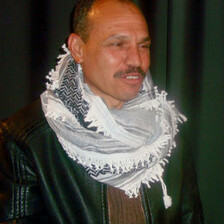

The Ofer military base is not an easy place to get into. But after most of my friends and the father of the family I was living with, Mohammed Khatib (also a leading member of the Bilin Popular Committee) were arrested in a brutal night raid on the occupied West Bank village of Bilin, I was determined to go to their court hearing.

Unfortunately, the taxi driver dropped me off at the wrong entrance. Four menacing Israeli soldiers faced me, and they did not look pleased at my presence.

“What are you doing here?” they demanded, “Don’t you know that no one is allowed here?!”

“No,” I replied, “I’m just here for a friend’s court case.”

“No you can’t, you must leave, go home now!”

Fortunately, one of the soldiers unwittingly pointed me in the direction of the court, before reasserting, “but you can’t go there.” Nevertheless, I was not intending to follow his orders.

Sitting outside were the families of all seven men on trial — although the term “men” would be misleading; five of the seven were aged 18 or younger. Also waiting to enter were a small group of international volunteers, hoping to observe the trial. But as usual with Israel’s so-called “democracy,” they would not be permitted to do so. Luckily for myself, I arrived at the same time as Lamia Khatib, Mohammed’s wife, and her insistence that I was a member of the family secured my entrance.

Once inside, I felt like I was at the heart of apartheid. We sat out all day in a Shawshank Redemption-esque yard, feeling jailed ourselves, with the unbearable heat beating down on our heads. As I sat on the concrete floor, staring at the youthful soldiers patrolling the cage we sat in, I couldn’t help but contemplate the occupation. When will the injustice stop? How can this be overcome?

At that moment, I could see it all around me. Right down to the Palestinians working for peanuts to repair the building behind us — cheap Palestinian labor is hugely exploited inside the green line, the internationally-recognized boundary between Israel and the West Bank, while the workers are treated as third-class citizens in their own homeland.

We were finally called for the hearing at around 3:30pm, even though it was due to start at 9:30am. In the court, the system of apartheid was even clearer. Despite the guards demanding the shackled teenagers not communicate with visitors, 18-year-old Mustafa couldn’t help but to shout out “HALA JODY!” when he saw my face. It was difficult seeing my adoptive family in brown uniforms, knowing they wouldn’t be freed in this sham of a trial.

The evidence presented against the defendants is known as “secret evidence,” meaning only the prosecution and the judge can see it, and hence no defense can be put forward. The whole process is conducted in Hebrew, a language most Palestinians don’t understand. Translation is kindly provided by a young Israeli soldier — yet another bitter irony considering the overwhelming force used to drag the boys from their homes in the dark of the night.

By the end of the day, there was no conclusion. No one was released.

Of course, the imprisonment of all the boys from Bilin is completely unjustified. After all, they are arrested for their participation in demonstrations against the wall, which defies not only international law, but also, in the case of Bilin, an Israeli high court order!

However, the arrest of Mohammed Khatib was particularly symbolic. As a senior member of the village’s Popular Committee, the Israeli authorities’ goal was clear — arrest the leadership in an attempt to crush the nonviolent resistance. In addition, the only alleged evidence against Khatib is the testimonies of two 16-year-old boys from the village, both of whom were subjected to interrogation by the Israeli army.

A few days later, I was back in Ofer for another hearing. This time, the prosecution presented a photo of a man throwing stones as evidence, who the two youths had “confirmed” as Mohammed Khatib. The defense attorney asked for the date when the photo was taken, which was given as October 2008. The defense attorney then presented the judge with Khatib’s passport.

Mohammed Khatib was not in the country in October 2008, he was in New Caledonia.

The prosecution’s case had been exposed for what it truly was — a political mission to put an end to the nonviolent resistance movement of Bilin, a mission in which they are doomed to fail.

The next day, a Friday, we marched to the wall again, as the residents of Bilin have been doing every Friday for the last five years. As usual, our peaceful protest was met with copious amounts of tear gas and sewage water.

After 15 days in prison without charge, we got a call from Mohammed’s lawyer, letting us know that, at last, he was going to be released. As soon as I heard the news, I jumped in the car with Ahmad, Mohammed’s brother, and their father, and we drove back to Ofer.

As usual, we waited outside for hours with no news. Finally, at around 7pm, we saw Mohammed’s smiling face walking towards us through the fence. After walking out, he turned and bowed to God, before coming to embrace his family.

It was difficult to know what to say. So I just smiled.

All the way home he told stories and laughed. As he told me later, “There is no comparison to the feeling of freedom.”

As we rounded the last corner coming into Bilin, we saw the flags which had been put up, the children running out onto the street with arms aloft, and Ahmad turned the music up full blast on the car stereo. When Palestinians are released from prison, it is tradition for their family to put up the flag of the political party they support. But for Mohammed, it wasn’t Fatah or Hamas waving in the sky, it was the Palestinian flag.

Our hero was home.

That same evening, Mohammed told me that being locked up as a political prisoner was something he felt proud of.

“Yes, the conditions were terrible, but I knew that the resistance was still alive in the village. I told the officer in charge of the operation, if you think that by arresting me, you will stop the demonstrations, you are completely wrong.”

Bilin will never, ever give up.

Jody McIntyre is a journalist from the United Kingdom, currently living in the occupied West Bank village of Bilin. Jody has cerebral palsy, and travels in a wheelchair. He writes a blog for Ctrl.Alt.Shift, entitled “Life on Wheels,” which can be found at www.ctrlaltshift.co.uk. He can be reached at jody.mcintyre AT gmail DOT com.