The Electronic Intifada Nilin 29 September 2010

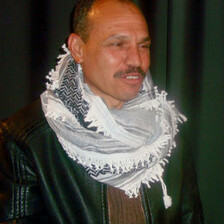

Hamoudeh Amireh moments after being shot in the leg by Israeli soldiers during a protest in Nilin, 17 September. (Saeed Amireh)

For more than two years the people of Nilin in the occupied West Bank have embarked on a campaign of unarmed grassroots resistance against the theft of their land by Israeli settlements and the wall. Twenty-seven-year-old Hamoudeh Saeed Abd al-Haq Amireh is part of this resistance. Originally a medic and the sole breadwinner for his household, Amireh became a self-taught journalist to cover the ongoing struggle in Nilin. During his work, Amireh has been arrested and injured by Israeli forces, most recently when he was shot in the leg on 17 September. Jody McIntyre interviews for The Electronic Intifada.

Jody McIntyre: Tell me about life in Nilin before the wall was built.

Hamoudeh Amireh: At first, for me, before the wall, the village was really quiet; people worked, even the settlers used to come in and buy things and deal with the villagers. Nobody would say anything or harm them or refuse them anything. After they decided to build the wall, and started putting up Israeli flags up and stealing our land, everything in the village changed; our security, living conditions, work, teaching and even our social life. People wanted to defend their land, and wouldn’t accept an occupying army building a wall on our land. During that period, there were a lot of clashes. The [Israeli] army would take the land of the families that live in this area, and when people dared to resist, they would use a brutal level of force in response. They injured a lot of people, with tear gas, live ammunition, or with rubber[-coated steel] bullets. I was working as a paramedic. I was born and grew up in Nilin, and I knew all the people in the demonstrations. So imagine, you see your friend, your neighbor or someone you care about injured, seriously injured, because the Israeli army doesn’t care if they shoot you in the head or somewhere else.

I was helping the emergency services, together with group of around ten other young volunteers. I’d had experience from the [second] intifada, when I used to work with doctors in Ramallah going out with the ambulances — we knew what we were expected to do. We used to go around in groups and help people who needed attention.

But when the demonstrations against the wall started here in Nilin, I saw that our media was very weak, and so no one was hearing about our struggle. The families from the village were building a strong resistance against the wall, but nobody knew.

It was this void in our movement which made me decide to quit first aid, and start filming the demonstrations instead. I had a normal camera, nothing professional, but I started using it even though I was lacking any previous experience and gradually began to learn new methods and techniques. No one was there to tell me how to film, but what led me to persevere is that I felt a need to have an archive of events about the occupation and its impact on the people and homes of the village, from cases I saw with my own eyes.

We have had five martyrs in Nilin since our struggle against the wall began, and when the last martyr [Yousef Aqil Srour] died, I was standing right there, camera in hand. At that moment, I knew it was my duty to film and record what was happening. But I am also a human being, and I knew the person dying in front of me. In fact, I knew him personally and we were very close. I felt torn, but I forced myself to film so that I could spread this image, so that people everywhere could see the suffering we are enduring at the hands of the occupation.

I wanted people to see that we are being wronged, that we are resisting peacefully, and that we don’t have weapons to use against anyone. We are using peaceful means to take what is rightfully ours. Everyone of our martyrs died while protesting peacefully; without carrying weapons and without using force. I think this is every human’s right. If their rights are taken away from them, they have the right to fight for them by any means. Despite this right, we defend our land peacefully, without any aggression, contrary to the reports of the Israeli army.

JM: When you started filming the demonstrations, did the Israeli army make problems for you?

HA: When I started to film, I didn’t know how the Israeli army would react, especially because I wasn’t attached to any press institution, but was filming as an individual. This made me afraid to get too close to the soldiers. Cameras are a sensitive issue for the army — they don’t like to destroy their [positive] image in the eyes of the world. They want to look righteous, as if they are the oppressed, the ones who have been deprived of their rights, but in reality this image is false and as their lies are being exposed and the horrors of the occupation are coming out, the world is starting to wake up to the reality of the situation.

After a while, I saw that I could be close to the army and they couldn’t say anything to me. The most they Would say was “go away,” and I would simply move a little further from them and continue to film from there.

About two months ago, I was standing with the paramedics during one of the demonstrations at the wall. I was filming the demonstration, and the paramedics were assisting people who had been injured with first aid, and suddenly the soldiers came through the gate in the wall and began running towards us. They arrested me and the young paramedics, and took us to the Binyamin police station for questioning. We had nothing to say, I’m a cameraman and the others were working in the Red Crescent ambulances. We were kept there, with our hands tied behind our backs and our eyes blindfolded, from around three in the afternoon until two in the morning. At around half past two, after further questioning, they sent a few of the youths home, but they took me and another young man called Jihad to Ofer prison. We stayed there from Friday until Sunday. On Sunday they released us because they couldn’t find anything to charge us with. Of course, we had done nothing wrong. It was simply another example of the army and Israeli government’s attempts to intimidate Palestinian journalists and emergency service workers.

JM: Do you have friends who have been arrested or injured in the demonstrations?

HA: Of course, and not just friends, relatives too. Two of my sisters’ husbands are in prison at the moment. Without any reason, purely because they go out on demonstrations against the occupation forces, or the “defense forces” as they like to call them …

In the village, everyone knows each other and we are all brothers, so when anybody is injured, imprisoned or is killed, you feel pain … a deep sadness, when you remember their suffering. The same goes for those who are injured or currently in prison for no reason — just for defending their land, for defending their dignity, for wanting to live like the rest of the people in the world. We ask ourselves, why do we have to live like this?

Even me, as a journalist, I’ve been imprisoned and I saw the suffering that the prisoners have to go through. The soldiers make you feel like you are a worthless individual, without any rights, without any purpose … as if you are not even human. And they are intentionally making you feel these things.

JM: After all the suffering and injustice you have seen, has there ever been a point when you felt like putting down your camera and giving up?

HA: No, not a single time. On the contrary, every single time I see the actions of the Israeli occupation forces I become more determined to film. After I had been imprisoned for filming the demonstrations I could have made the decision to stop, or become afraid. But I was determined to continue, to show the world exactly what is happening here in Nilin.

JM: After losing five martyrs in the first year of Nilin’s resistance against the wall, how do you keep the strength to go and demonstrate again and again?

HA: The Israeli army want us to think that if we go to demonstrate against the wall then there is a high chance we could be shot or killed, but I have never thought in that way. If I am killed, then it will be for a cause I believe in — this is my land and I am defending it. From the start, I knew that there would be a price, but whatever it is — death, suffering — I have to defend my land.

JM: As part of it’s campaign to crush the resistance in Nilin, the Israeli army imposed a curfew on the village. How did people react?

HA: No one followed the curfew. The army imposed the curfew to prevent people from getting to the wall during construction work, but they completely failed.

JM: While you were working with the ambulances in Ramallah, during the second intifada, what was the most difficult thing you saw?

HA: One day, the army entered the city suddenly, intent on arresting a young man. The jeeps came in and they started firing randomly. One young boy was walking and the army shot him in his lower body. Everything was torn … there was only flesh left hanging out. The other guys that were there couldn’t help him or even get close because if they did, they would also be shot. I was in an ambulance with the driver and one other paramedic, we were told what was happened so we went to the scene. The boy was losing a lot of blood and he was unconscious, so we carried him to the ambulance. There was blood everywhere.

It was very hard for me, because I saw that nobody was wondering how a child could be standing in the street without their mother or father, and someone just comes and shoots him, takes his life away without anybody defending him. I saw that we, the Palestinian people, don’t have anybody defending us. The occupation comes, takes, destroys and steals our land without anyone in the world raising their voice and saying this is wrong. Even now I see this often, and I feel that in the whole world we are really alone and nobody is defending us except God. That was the hardest thing I saw while working with the medical services in Ramallah.

JM: How do you see the popular resistance here compared to other areas?

HA: Even the occupation forces knows that it’s different here. They know that in Nilin the people don’t just come out to be photographed, or to get on the news. Our resistance is not a game or for show, and the result of this is the five martyrs we have suffered.

Also, Nilin is the only place in the West Bank, aside from the main cities, where they have been forced to build a concrete wall to steal our land. In other areas the wall consists of fencing and barbed wire, and at first they tried that here too, but it didn’t work. It didn’t stop the youth from tearing it down again and again, so eventually they were forced to build a huge concrete wall. They reserve the concrete for areas where the resistance is strongest.

JM: How do you see the future for Nilin?

HA: The future, we hope, will be that the wall here is brought down like the Berlin wall was brought down, and that the people of the village will achieve their goal of ending the occupation of our land.

JM: If you could send a message to the world, what would it be?

HA: My message to the world is to really look at what is going on in Palestine; we are occupied, we don’t have a country, we don’t have borders, but surely we have the right to live like like people live everywhere else in the world. The rest of the countries in the world should punish Israel for their crimes, impose international law, and stop the occupation in a way that won’t bring harm to anyone. We don’t reject Jewish people, but we fight the Israeli state because it has stolen our land and our country.

Jody McIntyre is a journalist from the United Kingdom. He writes a blog entitled Life on Wheels which can be found at jodymcintyre.wordpress.com. He can be reached at jody [dot] mcintyre [at] gmail [dot] com.