The Electronic Intifada 17 March 2009

The village of Aqraba.

The West Bank village of Aqraba sits nested in the Jordan Valley, approximately 20 kilometers southeast of Nablus and around 50 kilometers east of Israel’s wall that separates Palestinians in what is now considered Israel from those who reside in the West Bank. It is close enough to the Jordanian border that Palestinian cell phones roam here as if one were in Jordan.

There are 9,000 persons who live in this village, most of whom live on the top of the mountain, but these families have not always resided there. In 1968, shortly after Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip, when 400,000 Palestinians became refugees, many for the second time, hundreds of Palestinians from Aqraba fled to Jordan. Villagers fled upon hearing accounts of massacres in nearby villages, as happened in 1947-48, during which at least 700,000 Palestinians were forced from their homeland in a period referred to as the Nakba, or catastrophe. Historically the families of this village farmed and worked as shepherds, using the land stretching all the way to the Jordan River. But since 1967, Israeli occupation forces have continuously pushed families up towards the valley, a good 20 to 30 kilometers away from lands that used to belong to them. At first this forced removal was because the land was confiscated for a military training area. Then in 1973, part of that land was converted into the colony of Gitit on the mountain above Aqraba’s valley.

From the beginning the Israeli military and illegal settlers alike used force to make room for more colonies in the area. Abu al-Aez recalled his family’s flight in 1974 from the valley to the center of Aqraba on the mountain after the occupying Israeli army launched a rocket that hit their home: “Thirty dunums of land were stolen from us and now the settlers plant grapes there.”

According to official reports, last week the Israeli army issued orders to demolish six homes, their adjoining barns, one elementary school, and a mosque in the valley of Aqraba. However, families there say they suspect that up to 20 houses will be destroyed. On 26 March they are scheduled to have a hearing in an Israeli colonial court in Beit El, a settlement close to al-Bireh, to challenge this decision.

The roads leading down into the valley where the buildings slated for demolition lie are in Area C, while the part of the village on the mountain remains in Area B. Under the Oslo Accords the West Bank was divided into Areas A, B and C, referring to urban areas, built-up villages and rural areas respectively. Under this agreement the Palestinian Authority technically controls civilian life, including security; in contradistinction Area C is entirely controlled by Israeli occupation forces. One can tell the difference as one drives into the valley and the road changes from the paved road to a dirt road (though much of the paved road, like the electricity, was only installed two years ago). The Palestinian Authority exercises limited autonomy in Area B, while Area C — comprising 59 percent of the West Bank — is subjected to Israeli military administration. On one of the main dirt roads running through the agricultural land at the bottom of the valley — a road that was created by the occupying Israeli army — there are stones that have recently been marked with red spray paint. Villagers believe this indicates that their homes will be demolished in order to create a Jewish-only road connecting the surrounding, illegal Israeli colonies of Gitit, Itamar, Yitzhar and Hamra.

Like many villages in the West Bank surrounded by illegal Israeli colonies, the areas of Aqraba are invaded by Israeli forces daily and Israeli settlers regularly. Between 1975 and 1982 shepherds were regularly arrested by the Israeli army. Their sheep were confiscated while the shepherds were in prison and they were forced to pay 10 Jordanian dinars per sheep to get them back upon their release. Since the second Palestinian intifada broke out in September 2000, at least one shepherd per year has been murdered by Israeli settlers. Most famously, in September 2008, Yahia Ateya Fahmi Bani Maneya, an 18-year-old shepherd, was murdered by settlers. These daily threats since 1967 have meant that numerous families who own land in the valley for grazing their animals and growing food — fava beans, lentils and wheat — have sold their livestock and moved to the part of Aqraba at the top of the mountain. Those who have moved, but who have tried to continue to tend to their land, have been prevented from doing so by the Israeli army.

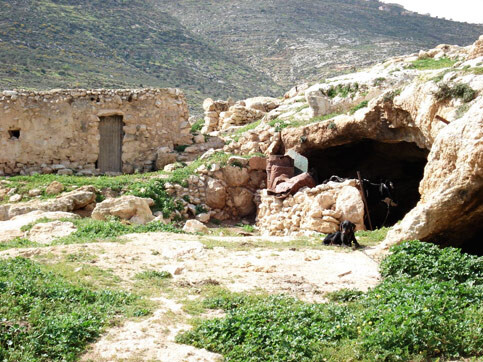

Driving into the valley, one notices that there are still shepherds out with their sheep grazing the land. The village itself is 250 years old, although all of the original homes are more than a hundred years old. As families have expanded they added onto the original structures, which they still use. The history of these families on the land can be traced as these homes are built next to the caves that their families inhabited with their sheep generations ago, prior to building homes. The elementary school and the mosque are newer, but these buildings, like the homes, are all slated for destruction in this latest episode of ethnic cleansing, which will affect the 200 people residing in this valley for generations. These are the remaining families who have not fled to Jordan nor to the center of Aqraba.

Two young girls, Lubna and Maram, of the Anas family.

Every family in Aqraba has a similar story to tell: of relatives fleeing in 1967 to Jordan, of relatives fleeing to Aqraba’s center and leaving their agrarian way of life, of the looming dispossession. Like many of the families from Aqraba, Fatima and Maher Anas trace their families back for generations and their migration from cave to home, part of which was built more than 200 years ago. Like many other families, much of their livelihood has been destroyed by Israeli army bulldozers that destroyed all of their wheat last year. Many of their relatives fled to Zarqa refugee camp in Jordan, joining the fate of other Aqraba families.

Reflecting on what will happen if the remaining part of her family is turned into internally displaced refugees, Fatima explained, “If they destroy our houses they will destroy our crops and our ability to make food. If we cannot plant food any longer, what will happen to our livelihood?”

Fatima’s brother, Yusef, has already faced this fate. Across the way from the mosque scheduled to be demolished is the foundation is Yusef Nasrallah’s home. He started building it last year only to be ordered to stop by the Israeli army. Like many before him, Yusef sold his sheep and moved to Aqraba’s center where he has been unable to find work.

To be sure, this latest phase in the ethnic cleansing of Aqraba is not unique to the West Bank nor to the part of historic Palestine that is now considered Israel. This week saw the destruction of two Palestinian homes and 100 olive trees in the Negev town of Beer Seba, now given the Hebraized name of Beersheva. In the West Bank, from Qalqiliya to Hebron to East Jerusalem, families await the status of the orders for their homes to be demolished. But while there is a great deal of attention paid to the impending destruction of Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem, there is little if any media attention or support for families in small villages like Aqraba. In the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Silwan, Palestinians flock to the demonstration tent set up to show solidarity, but there has been no such solidarity presence in Aqraba. Israel’s colonial divide-and-rule policy continues to fragment the people in ways that separate them physically by its system of checkpoints and permits. But this is not about the occupation of the West Bank. Indeed, these same methods were used to confiscate large land tracts during the 1948 catastrophe. It is an ongoing Nakba that requires learning the lessons of history by not submitting to the divisions imposed by the colonial regime.

All images by Dr. Marcy Newman.

Dr. Marcy Newman is Associate Professor of English at An Najah National University in Nablus, Palestine. Her writing may be found at bodyontheline.wordpress.com.