The Electronic Intifada 20 March 2014

Many people may have heard stories of Israeli soldiers traipsing around Goa’s beaches after completing their military service.

But how many are aware of the military and economic ties between India and Israel?

As Israeli prime minister, the late Ariel Sharon signed an agreement with the New Delhi government in 2003, declaring that India and Israel were “strategic partners.”

Since then, Israeli technology and tactics have been deployed regularly by Indian forces occupying Kashmir.

Over the past few years, meanwhile, the state of Haryana has concluded a deal for managing sewage with the Israeli water company Mekorot, and Elbit India — a subsidiary of the Israeli weapons-maker Elbit — has invested heavily in factory farming in Andhra Pradesh.

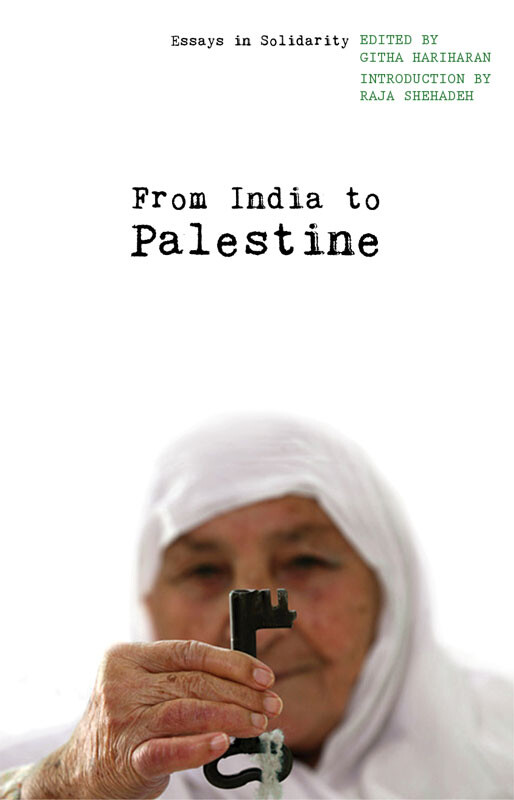

To understand how India shifted from being a bulwark against imperialism to allying itself with western interests, one can gain a great deal of insight from Githa Hariharan’s edited collection From India to Palestine: Essays in Solidarity (LeftWord).

The book features fourteen essays by Indian writers, scholars, and activists as well as a contribution by noted Palestinian author Raja Shehadeh.

The essays range from first-person narratives about visiting Palestine to examinations of the changing nature of Indian relations with the Palestinian people and with Israel.

Anti-colonial legacy

The book opens with a poem by Mahmoud Darwish and two touchstones highlighting India’s historical relationship with Palestine: by Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first prime minister). The latter two are alluded to at various junctures in the anthology.

A few essays in the book ground this anti-colonial legacy, laid out by Gandhi and Nehru, by illustrating the tangible effect of their words.

Novelist Githa Hariharan describes her first trip to Palestine in 2013 through the lens of a childhood memory that many Indians recollect: “Like many growing up in India in the 1960s, my first awareness of Israel came with the Indian government’s ban on travel to Israel. At the age of twelve, an official blue stamp on my first passport said: ‘Valid for travel to all countries except Israel and South Africa.’ I learnt, via the government, that there was something wrong with Israel and South Africa.”

Hariharan builds the case for an academic and cultural boycott of Israel in India against the backdrop of a radically changing Indian government.

She aptly characterizes this attitude shift as “amnesia about Palestine in India — bred by this new relationship with Israel.” This amnesia is emboldened by how both governments have bonded over their “wars on terror.”

The book includes texts that alleviate Indian amnesia by engaging with Gandhi or Nehru on Palestine. A.K. Ramakrishnan’s contribution analyzes Gandhi’s 1938 essay “The Jews in Palestine.”

He roots oft-quoted statements by Gandhi, such as “Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French,” in a strongly anti-colonial context.

“Naked terrorism”

While Gandhi believed “in the inseparability of religion and politics,” he rejected the intertwining of the two when it came to Zionism.

Two years before the State of Israel was founded in 1948, Gandhi wrote: “They have erred grievously in seeking to impose themselves on Palestine with the aid of America and Britain and now with the aid of naked terrorism.”

Through this essay, Ramakrishnan reminds readers of the fact that colonizing Palestine meant that Zionists collaborated with the same imperial powers Gandhi fought against in India.

Although Nehru played a significant role in opposing British colonialism, the book pays less attention to his role than readers might prefer.

His niece, novelist Nayantara Sahgal, nonetheless draws a connection between Nehru’s anti-colonial position regarding Palestine and his struggle against the British: “Locating Israel on Biblical terrain had less to do with sympathy for Zionist sentiments than Britain’s need for a European ally in West Asia to safeguard the Suez Canal route to India.”

This shared struggle between Palestinians and Indians is emphasized by the remaining articles in the volume. Essays by Vijay Prashad, Meena Alexander, Prabir Purkayastha, Sunaina Maira and Seema Mustafa provide insight into how you can begin to learn about Palestine in spite of a misleading media or an absence of resources.

Changing relationship

Purkayastha examines the changing relationship between India and Israel in ways that build on the earlier historical material so readers can examine how much India is changing, too, for the worse as its ties with Israel become stronger.

Aijaz Ahmad’s essay provides a satisfying conclusion as he inspires readers to see why it is essential to participate in organizing for Palestine: “Palestinians are facing not a primarily local enemy as the Angolans or Namibians or even in some respects the South Africans did; they face a global enemy, and they need to win globally.”

Ultimately, Ahmad also turns to the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement as the primary tool for people to support Palestinians.

This collection contributes to literature on the expanding solidarity movements and the histories they grow out of. Importantly, the book gives one a sense of how to direct one’s energy.

The terrain the book explores also leaves some new directions for other writers to research about the normalization of relations between Israel and India.

But regardless of what you do with the knowledge gained from this fascinating book, you can no longer feign amnesia about India’s history of supporting anti-colonial movements.

Marcy Newman is a writer, teacher and activist based in Bangalore. She is a founding member of the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel and the author of The Politics of Teaching Palestine to Americans: Addressing Pedagogical Strategies.

Comments

Book

Permalink Bobby replied on

Where can I get my hands on this book?

How can this not mention

Permalink Anonymous replied on

How can this not mention Bacha Khan?!

http://www.insightonconflict.o...

Instead of voting to get

Permalink Arjun replied on

Instead of voting to get people to divest from Israeli products and services, I personally feel that voting for closer ties and peace between palestine and israel would have had a more lasting and strong impact. It would show students in good light and the university itself as promoting good will.

By creating blogs of anger and hate(which seems pretty obvious) one is only asking for more trouble. Isn't that how karma works?

India and Palestine: Connected by struggle

Permalink Yesh Prabhu replied on

I think millions of Indians, especially those under the age of 45, do not know that decades ago India was a strong supporter of Palestine. They do not know that Mahatma Gandhi was a strong supporter of Palestine and that he had great sympathy for the Palestinians. He said that Peace is based on Justice. Without justice there can be no peace. The reason all the peace proposals regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict have failed so far is that none of the proposals were based on Justice: Justice for the Palestinians who were driven out of their lands using brute military force. Mahatma Gandhi had said: “Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct.” The annexation of Palestinian lands by Israel continues even now as I am writing these words. Look at all the peace proposals, and pay attention to what Kerry says, as he travels around the world talking about “Peace”: The word “Justice” is missing. And there in lies the reason that all these peace proposals have failed.

It is a mystery to me why India has formed close ties with apartheid Israel. After all, Israel is a brutal colonizing power, and India knows what it is like to live under military occupation. It’s bad enough that President Obama dances to Netanyahu’s music at the White House; that Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, too, has started to dance to Netanyahu’s discordant music is a great tragedy. I wonder what Mahatma Gandhi would have said had he been alive now.

Yesh Prabhu, Bushkill, Pennsylvania