The Electronic Intifada 25 June 2024

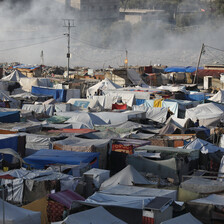

Al-Mawasi has become crowded with the tents of displaced people.

APA imagesThe story began on 7 October, when Gaza’s landmarks changed, and l lost many loved ones, friends, and even dreams.

My life had been simple and calm, despite all the difficulties l was facing.

I was satisfied with my life and excited about starting work as a dentist.

I graduated from the faculty of dentistry at al-Azhar University in Gaza in June 2023. After five years of hard work, searching for patients to complete my academic courses and paying a lot of money — $4,000 per year — I joined the program to practice to be a dentist.

After a full year of training in private clinics and the government sector, I would obtain a dentist’s license to work in the profession and open a private clinic. Like many new graduates, I was full of energy and ambition.

I worked in a private clinic in September, which was located near my home, and trained with the wonderful and loyal Dr. Israa. The environment was comfortable and encouraging to work in. During the month of training, I learned a lot and met many dentists.

Work was suspended due to the Israeli attacks in October. I thought that with every escalation, the bombardment would last another week and the matter would end. But the genocide went on and took days from me.

Then, the clinic in which I was training was bombed and a lot of private clinics were also destroyed. Dr. Israa suffered a fractured skull and burns on her body.

Being displaced

I was displaced for the first time. I moved from the western Gaza area to my uncle’s house in western Khan Yunis, following the orders of the Israeli military to evacuate northern Gaza and head to the southern area.

l left the house with only a few clothes, official papers and certificates, hoping that we would return soon. I stayed with my uncle’s family for nearly a month, and then an order was issued to evacuate the Khan Yunis area, which had become a battlefield, and head to Rafah.

l moved to my grandfather’s house in the Brazil neighborhood, a border area classified as dangerous. There were approximately 60 people staying in the two-storey house, and we were only using two bathrooms. There was a shortage of clean water, and while washing dishes or clothes, some in the house were infected with gastroenteritis and hepatitis A.

As the news increasingly reported about the Israeli military’s intention to invade Rafah, I and some others decided to leave the house and move to an apartment

The rent was $500, and we were finding it difficult to pay because there was no financial liquidity. We were not allowed to withdraw money from a bank without paying a commission of up to 30 percent.

But I felt stable in Rafah and decided to try to complete the internship training in government clinics, as a result of the continuation of the war. I was asked to bring my graduation certificate from the university, which I had left in my uncle’s house, which had been bombed.

I now had no proof of my graduation from the university. I felt helpless and frustrated as I went back and forth to the officials more than once trying to get them to allow me to work.

I contacted officials at the university and was able to obtain a copy of my degree. There were many campaigns to allow students stuck in Gaza to complete their studies abroad, and I registered to do so, but after the invasion of Rafah and Israel controlling the crossing, I lost the opportunity.

The Israeli military entered Rafah. It had already occupied the Rafah crossing. Throughout it all, the bombing continued. Leaflets were dropped ordering the evacuation of the eastern area of Rafah.

I lived through nights of terror. The question that haunted us was where to go next.

We decided temporarily to move to my aunt’s house located in what is considered the Saudi neighborhood of Rafah. We planned to search for some empty land to put a tent on and build a bathroom. After we prepared the tent, we moved to Mawasi, west of Khan Yunis.

Thousands of displaced people live there in inhumane conditions, drinking polluted water and bathing in the sea, their only outlet in the extreme heat. Their tents face the street or the sea, and flies, ants, and mosquitoes spread are everywhere. At night, the weather is cool, but the wind is so strong it can uproot the tent.

Nothing is important

There is no privacy in a tent. We hear the conversations in neighboring tents, and we wear prayer dresses all day despite the hot weather. Five or 6 families share one bathroom.

We do not have a kitchen. We cook in the open on wood fires. With the closure of the Rafah, there is no cooking gas to be found.

The Israeli military has destroyed the local hospital. An association recently established a medical facility in which a general practitioner and some specialist doctors treat people.

I do not feel like I belong to this place. I want the war to end and to return to my home.

My day is usually spent on just three tasks: providing salty water for hygiene, sweet water for drinking and cooking.

Nothing is important to me anymore. I no longer follow the news.

There are many tents here, some have been made by hand, which costs less than ready-made ones.

There are many stalls: barber shops, charging points, places that refrigerate food and drink for a fee, clowns to entertain children, and rest houses that provide Wi-Fi and clean water

Israel’s assault betrays its goal, namely genocide. Why else destroy hospitals, universities, many medical centers, and dental clinics?

Israel has targeted doctors and dentists. Some doctors sold their clinics to save their lives and leave Gaza. They will try to start a new life abroad.

My old faculty of dentistry at al-Azhar University has also been destroyed. Students’ lockers containing their equipment are gone, their parents’ money wasted.

All I want is to return to my home and for the sea to become a spot to visit for leisure, not a place to live.

Tasneem Elholy is a dentistry graduate based in Gaza.