The Electronic Intifada 4 November 2009

Though the memoir was originally written in Arabic, Cortas’ daughter Mariam Said explains in the book’s introduction: “She felt compelled to write in English to explain to the West the politics around the Palestinian tragedy …” (xxviii). Before her death in 1979, Cortas gave the manuscript to Mariam’s husband, the late Palestinian thinker Edward Said, for publication. At first, the family was unable to find a publisher. But after the 11 September 2001 attacks and subsequent US-led wars in the Middle East, the region became the focus of much of the world. It was then, Mariam Said writes, “that the time for her book had come” (xxix).

Cortas’ story begins in 1917, the year of the infamous Balfour Declaration in which the British promised Arab Palestine as a national home for the Jewish people, and the year before an old empire would be replaced with a new one. World War I marked the end to centuries of Ottoman rule and the beginning of the French and British Mandate over much of the Middle East; Syria and Lebanon fell under the control of the French. While growing up, Cortas had no choice but to become involved in politics. Her father, a professor of Arabic at what is now the American University of Beirut, sent her to the still-operating secular Ahliah National School for Girls in Beirut. She learned much through him and his intellectual colleagues who would meet at the family’s home to discuss issues of the time. Throughout the book, she quotes her father’s lessons: “ ‘No one loves us for our black eyes,’ goes a saying that Father often repeated. ‘These big nations are selfish; their major aim is to use us as tools to further their interests and ambitions’ ” (34).

Her father’s words would prove true when Cortas returned to Lebanon after studying in the US and became principal of Ahliah School in 1935, a position she would hold for four decades. Cortas, who “hated to be addressed in French,” felt the effects of French colonialism and “could see that bit by bit Lebanon was being detached from its Arab roots” (80). She bravely went against many in Beirut who “wanted their children to speak French fluently” (80) to see that Arabic be the primary language taught at Ahliah, even though her insistence left the school with “no allies” as some, including an important politician, withdrew their kids from the school (81).

Cortas also accused the French authorities of undermining Lebanese unity by “emphasizing sectarianism” in Lebanon (80). Unfortunately, Cortas fails to further explore this important point and there is little discussion of how the French colonial rulers oversaw the establishment of the confessional system in Lebanon which divided the population along religious and sectarian lines, leaving the Christians with a majority of the power in government. This confessional system still exists today, fueling Lebanon’s many internal conflicts.

For Arabs like Cortas who believed in a united Arab world free of foreign occupation and colonialism, Palestine was, and remains today, a rallying point. Like many at the time, Cortas grew up when Palestine was the “southern part of Syria” (33). While studying in the US she said of herself and the other Arab students that “Palestine was our common denominator, the core of our thoughts and aspirations” (67).

At age 18, Cortas traveled to Palestine with her school where she witnessed the active Zionist movement and describes their kibbutzim as being “detached from the life of the area” (39). She was keen in her understanding that this was happening under the auspices of the British mandate in Palestine, and thus her distrust for Western powers deepened. Like many Arabs at the time, Cortas suspected, that the intentions of the Zionist settlers in Palestine were not entirely pure, noting, “Arms were pouring into the land where Jesus had spoken of peace and love” (39).

Cortas emphasizes the distinction between Zionism and Judaism. She met Jews in the US opposed to Zionism, including a prominent Jewish family in Detroit who told her that “ ‘Judaism is a religion and not a nationality’ ” (63). Cortas also grew up knowing many Jews in cosmopolitan Beirut who opposed Zionism. Prior to 1948, thriving communities of Jews existed throughout the Arab world. In Lebanon, much of the Jewish community remained up until 1982 when Israel further invaded the country and occupied the capital Beirut, and — incidentally — bombed the synagogue in the heart of the city damaging it badly. Cortas’ story offers a counterpoint to crude Israeli claims that Arab opposition to Zionism stemmed from anti-Semitism. It reminds us too that for Arabs, Jews who had always lived among them, were not the issue, but rather Zionist colonialism.

As 1948 neared, when Israel was established and the Palestinians were expelled from their homeland, Cortas’ worry increased. She makes careful record of each news event as it happened, and combines it with letters from some of the Palestinian boarding students at Ahliah whose concern also deepened as they wrote letters to their families in Palestine. The assassination of a UN diplomat mediating in the Palestine conflict, Zionist aggression at the expense of the Palestinian people, and the failure of the UN or Arab League to put an end to the violence led Cortas to sympathize with the armed resistance movements that emerged in the 1960s. She reverted to her culture to make sense of those who had taken up arms: “ ‘Who taught you to be tough?’ goes an Arabic proverb. ‘My neighbor who died in suffering’ is the answer” (160).

As Palestinian guerrillas led cross-border raids from Lebanon into what became Israel, she writes, “More hope filled our hearts as our freedom fighters crossed the wires and aroused the fear among the aggressors. For me, it was the hope that the aggression would stop, that resistance would command the world’s attention and force a just solution to the Palestinian crisis” (153).

Soon after the armed resistance grew in support and a spirit of revolution had taken over Beirut, Lebanon quickly spiraled downward into the start of its civil war. As right-wing Christian militias supported by the West battled Palestinians and their Lebanese allies in Beirut, Cortas offered a general condemnation saying the country had fallen “prey to insane youth whose true desire was to play havoc with everything” (174). She rejected the propaganda of right-wing Christians who claimed that it was the Palestinian “ ‘strangers’ waging war against the Lebanese” (175). To this, she angrily replied, “Had we forgotten that this was a civil war? We, who had always considered Lebanon an integral part of the Arab world, a place where human horizons could expand freely — we were talking about ‘strangers’?” (176).

Cortas would live her last years during the civil war and die of natural causes in its midst, spared the brutality that would continue for more than a decade longer.

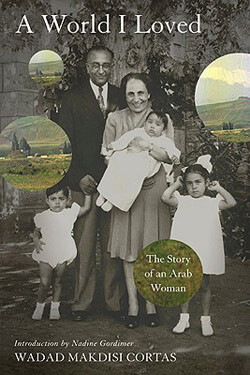

At times, Cortas’ memoir can be frustrating for those wishing to know more about the personal life and feelings of someone who witnessed this turbulent history. Her husband Emile Cortas, a successful businessman in Beirut, is mentioned only a handful of times. Edward Said is referred to only as “the scholar” and never as the husband of her only daughter, Mariam. Likewise, her brother-in-law Constantine Zurayk, the famous Arab historian who coined the term “Nakba,” or “catastrophe” that describes the forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948, is referred to merely as “the historian.” The thorough introduction and inset of collection of family images from her daughter Mariam are essential guides for the contemporary reader to make sense of what might otherwise seem an incomplete narrative. However, the selfless narration suggests the author was a person who cared more for her people and their interests than she did for herself.

Readers cannot ignore Cortas’ privileged class status that at times prevents her descriptions from getting closer to the real hardships experienced by Palestinians who left their lands with nothing and ended up in camps around Lebanon, or the popular Arab class who suffered immensely during the many wars of the 20th century. Her accounts sometimes come across as insensitive, as she jumps from describing a war to taking a vacation or leaving to the mountains above Beirut where she and many who could afford to escaped while the fighting raged in Beirut. That is not to say that Cortas took her privilege for granted; on the contrary, she volunteered much of her time and was active in various fields, always concerned with the issues facing the Arab masses, not only the privileged in Beirut.

The world Cortas loved was, ironically, not a world in which she ever lived — where the Arab world was liberated of its foreign occupiers and its peoples were free to choose their destiny, where individuals embraced their shared and long-standing culture and saw past petty differences between them. She fought for this world. Cortas’ story provides much needed context to a largely misunderstood part of the world where events are often portrayed as isolated incidents. Her memoir is a must-read for anyone wishing to understand the roots and the people of the present-day Middle East and the decades of war that have greatly affected the region.

Matthew Cassel is an independent journalist and photographer based in the Middle East.

Related Links

- Purchase A World I Loved on Amazon.com