The Electronic Intifada 13 May 2016

“What did we do to deserve to die under the bombings and for the Arab countries to not want us?” asked Basima, a mother of seven children, in Baalbek, a city in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

The lives of Palestinian refugee families who have fled Syria to Lebanon are suspended and their futures uncertain. Denied their right to return to Palestine, from where they originate and have hoped to return for decades, they were more recently uprooted from their homes and, for many, their relatively comfortable lives in Syria.

Lebanon currently hosts one million Syrians — one out of four persons in the country is a refugee. More than 100,000 of the 560,000 Palestinians in Syria registered with UNRWA, the United Nations agency for Palestine refugees, have fled the country — approximately 42,000 of them to Lebanon, according to the agency.

For Palestinian refugees from Syria, Lebanon is an unwelcoming place. Like Jordan and Turkey, its government has placed measures to discourage Palestinian refugees from entering. A freeze on visa renewals means that many Palestinian refugees from Syria living in Lebanon are in an especially precarious position, living on the margins without access to basic services.

While Lebanon and Jordan have signed an agreement with the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR on offering refugee protection to Syrians, the deal does not apply to Palestinian refugees from Syria, who are only able to access the very limited humanitarian services offered by chronically-underfunded UNRWA.

Palestinians who fled Syria to Lebanon join the nearly half million Palestinian refugees who have been in the country for decades, living in already overcrowded camps and contending with various forms of economic and social discrimination — conditions much worse than those in Syria before the war.

Some families left Syria with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, like their forebears who were forced to leave Palestine by Zionist militias in 1948.

“My parents were kicked out from Palestine. I was also kicked out. This is our destiny,” said Samira, 53, who currently lives in a rented home in Baalbek, a city north of Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

As Palestinians mark the anniversary of the Nakba, the ethnic cleansing of Palestine nearly 70 years ago, there is no end in sight to their repeated dispossession.

The following photos feature four refugee families living in Shatila camp, in Lebanon’s capital, Beirut, and in Baalbek.

Anne Paq is a French freelance photographer and member of the photography collective ActiveStills.

Lubna, 8, dressed in her school uniform, stands in her new home in Shatila refugee camp. Her mother, Muna, is Syrian; her father is a Palestinian refugee. Despite the trauma of having left Syria, Lubna and her sister are doing well at the UNRWA school that they both attend. The family fled from Yarmouk camp near Damascus in 2013 because of the fighting that erupted there. The family of four are now living in an unsuitable two-room flat, paying rent of $250 per month excluding utilities, and don’t have extended family nearby to lean on.

“The home is dark all the time. Our mattresses get wet. We get sick, but the other homes were too expensive,” Muna explained. She does not leave the flat except to go to the market and has only one friend in the camp. Her husband does not have residency rights. He therefore cannot not leave the camp, lest he risk arrest, which makes it more difficult to find work.

Garbage is often left directly in front of Muna’s home. “In Yarmouk, we had a nice home with a garden. It was like a big village in Yarmouk camp,” she said. She also feels discriminated against in the camp. “When I say I am from Syria, people react like I have a disease,” she explained.

Her husband Muhammad said: “In Syria, we did not feel any difference of treatment. We were like one. Here there is discrimination. I cannot even go back to Syria, because the government wanted me to go to the army.”

The situation puts a lot of pressure on the couple and Muna said that she now fights daily with her husband. “I told him to find a European woman and go there,” she said, half joking.

A photo of Naja’s husband, Salih, on their television in their new home in Beirut’s Shatila refugee camp. Salih, who is still in Syria and works as an electrician, has not been able to visit his wife and children for the last two years. Before then, he went back and forth so that he could continue to work in Syria. But with increased restrictions at the Lebanese border, he could not continue.

Naja is raising her three children without her husband while living with other relatives. “Everything is difficult here. We do not have rights, no protection. We don’t have residency papers. In three years, we have only been a few times to the sea and this is it,” Naja said.

“I fear for my children here, there are drugs and bad people around. I want them back home right after school,” she added. “We would like to go back to Syria, as soon as possible.”

Naja’s mother, Sada, with her two granddaughters. Sada is from Safad, in present-day Israel, but was born in Yarmouk camp near the Syrian capital. Five of Sada’s children are still in Syria. Sada and Naja check the news from Syria all the time and worry for their loved ones.

Naja explains that her third child, 11-year-old Ibrahim, wants to go to Europe to collect money to help his family. He attempted a dangerous sea journey months ago with a friend of the family but they could not board the boat in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli as there were police around.

“If he wants to try another time, I will agree,” said Naja.

“I don’t know what the most difficult thing is. I feel depressed and sad. It’s difficult without a husband. I talk to him all the time in my head,” said Sara, standing in her new home in Shatila refugee camp. She and her six children came to Lebanon two years earlier from Sayyida Zaynab, a suburb close to Damascus, after fighting broke out and their home was set on fire by militias. They lost many belongings.

Before then, her husband went to work one day and never came back. They made inquiries but found no information. Sara was actually born in Shatila. She fled after the 1982 massacre in the camp by a Lebanese militia allied with the Israeli military during which her mother was killed.

“I have seen so many wars. I have nightmares all the time,” she said.

Yasir writes poems, acts and directs theater performances, plays in a band and works with other refugees. “Helping Palestinians here is my responsibility,” he said. Yasir, his mother, his two brothers, his sister and her two children came to Lebanon in 2012 and found a home in Baalbek.

His family comes from a village near Safad in present-day Israel. But Yasir was born in Libya and raised in Yarmouk camp near Damascus, where he owned a small shop. When a siege on the camp imposed by Syrian government forces intensified, he could not reach his shop and his family left the camp. As with so many families, they split up; his father is currently in Sweden.

Yasir has only one thing in mind: leaving Lebanon to reach Europe. He already tried four times through different routes, and was arrested in the process, but he is ready to try again. “I want to keep trying. It’s better than staying here. I don’t feel safe and I cannot really work,” he said.

Yasir keeps one passion alive: the history of his original village and his family. “I did some research about my village and I wrote it all down. I also had some recordings. I lost everything in Yarmouk. The worst thing was to lose a plant which was growing in some earth that my great-grandfather took with him when he left his village,” Yasir said.

Tala, Yasir’s 5-year-old niece, in their new home in Baalbek. Her father, Ahmad, disappeared when he was leaving Yarmouk with his wife and children. He and three other men were taken away by government forces when their bus was stopped at a checkpoint. They never heard from him again. Tala’s mother, Asma, escaped with her children, and joined her mother and brother in Lebanon.

“People who disappeared, they are probably dead,” said Asma’s mother, Samira. Asma said she has no choice but to wait. “I am shocked and upset. Not only for my husband, but for all the men that were taken away. I am waiting. I have hope,” she explained.

“All day I sit at home. I feel bored and depressed,” said 18-year-old Aya, who fled Yarmouk camp and lives with her mother and two siblings in al-Jalil refugee camp in Baalbek. The family is originally from a village near Tiberias in present-day Israel. She was studying in Syria but in Lebanon the system is different and she does not go to school, although she regularly goes to a cultural center where she has made many friends.

Aya’s family does not have residency rights so they do not move around for fear of arrest, and remain confined in their home most of the time. Her father is currently in Germany where he is waiting for his residency papers, with the hope that the rest of the family will join him. Her elder brother, Nasser, works in a supermarket, and makes $250 per month.

Aya (left) with her mother and brothers. “In Syria the situation for us was so much better. We had a whole building, with four floors with our extended family. Now we are all scattered and we feel isolated,” she said. She worries for her friends and relatives left behind. Her uncle who was working as a medic was killed by a sniper in Yarmouk camp and his wife and children are still there, unable to leave. Aya’s mother tries to hold the family together.

“My mother is the mother and the father now. My father left a big hole. At first it was very difficult, but with time, we got used to it and we manage,” Aya explained.

The daughters of Basima (seen at the top of this page) in their new home in Baalbek, one of them looking at a photo of her brother, 16-year-old Ahmad, who is currently in Germany. Basima’s family fled Yarmouk camp to Baalbek in 2012. Once home to 150,000 residents, Yarmouk was formerly the largest Palestinian population center in Syria before it became an arena of fighting in December 2012.

Thousands fled after rebel forces entered the camp and its central mosque was hit in government airstrikes. Several thousand civilians remain in the camp, living in dire conditions after years of government bombings and siege, and the water and electricity lines cut. The Islamic State militant group now controls a large part of the camp.

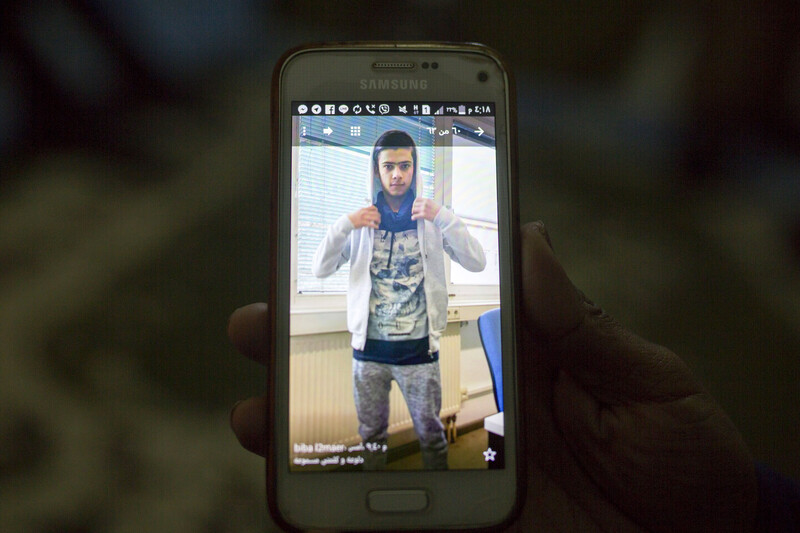

A photo of Basima’s son, Ahmad, on her mobile phone. Basima sent him to Europe via Turkey. He reached Greece by sea and then Germany by land. The journey cost approximately $4,000. Ahmad is now in Berlin with his cousins and is going to school there.

Of the family’s situation in Lebanon, Basima said, “We have papers, but my husband has only 20 days left before they expire. They don’t give asylum to us. If they catch us working, they detain us. If things are better in Syria we would like to go back there. If not, we want to reunite with our son in Germany.”