The Electronic Intifada Beirut 7 September 2012

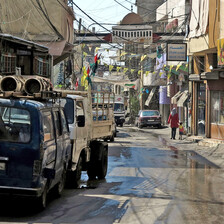

Palestinian refugees from Syria are fleeing to Lebanon’s already crowded refugee camps like Burj al-Barajneh.

APA images“If I wasn’t running for my life I would never set foot in Lebanon,” said Um Ahmad. “We Palestinians are treated by the Lebanese as if we are not human. But we’ve learned to cope, breathe hope and live in the hope that we will finally return to our land in Palestine and experience how it feels to live in dignity in our own country. Dignity is something we have not been able to experience since 1948.”

A few weeks ago Um Ahmad, 52, fled Germana camp in the Sit Zaynab neighborhood of Damascus and is now taking refuge at Burj al-Shamali camp in Tyre, Lebanon.

According to the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA), there are more than 470,000 Palestinian refugees in Syria. Palestinian refugees fled to Syria after they were pushed out of their homeland in 1948 during the establishment of the State of Israel.

Denied their right of return, Palestinians have held refugee status for nearly 65 years. Palestinian camps in Syria were still considered a safe haven until three months ago when they began to be affected by the clashes between Bashar al-Assad’s regime and rebel fighters.

The UN refugee agency UNHCR recently published estimates that 43,760 Syrian refugees have taken shelter in Lebanon since last year. The Lebanese government has a flexible entry policy for Syrians seeking refuge in Lebanon. A Syrian refugee is allowed to enter Lebanon without entry fees and can stay for a period of six months, or longer, subject to renewal.

Discrimination

But the situation changes when a Palestinian refugee is fleeing the same precarious circumstances and areas as Syrian nationals.

Palestinian refugees fleeing to Lebanon from Syria are only permitted to stay for one week; after that, they have to renew their permits which cost $33 for each person above the age of 10. The fee, as little as it may be, is difficult to come up with in a place like Lebanon where Palestinians are banned from work.

Mahmoud, 23, recently arrived to the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut. Until then, he had been living in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus, which has been hit by shells on a number of occasions. More than 20 persons were reported to have been killed in an attack on Yarmouk in early August.

“We had to flee the violence surrounding the Yarmouk camp. My aunt lives here in Shatila, but her house is too small to fit our family and her family. We just moved to a one-room apartment two days ago. It’s in the building right next to my aunt’s.

“The owner, a Palestinian, will rent it for $250 a month but we don’t have to pay him now. To tell you the truth, I don’t have that kind of money at the moment. When we left our home in Yarmouk we left with the clothes we had on us. My mother had $300 saved but we spent it all on transportation and food.”

“No phone number, no entry”

Not every Palestinian refugee fleeing Syria can get into Lebanon. The Lebanese border control authorities demand an address and a phone number of a relative or friend residing in Lebanon.

While crossing to Lebanon, Um Ahmad was confronted by a security guard: “He said, if there is no phone number you need to go back to where you came from in Syria. I told the security officer, you should have some mercy, you know that we are running away from war, we are not here on a vacation. He replied: no phone number, no entry.”

Luckily, Um Ahmad was able to provide a phone number, but the story doesn’t end there.

“We had to bribe the Syrian border control security officer to be allowed crossing to Lebanon,” she said. “We had to pay $15 each. When we reached the Lebanese border they made us pay a fee of 50,000 Lebanese pounds [$33] for each one of the five of us. I have been here for 14 days.

“When we went to renew our one week permit from the Lebanese authorities, we were told there is no renewal for Palestinians. The Lebanese authorities informed us that when we exit Lebanon we will have to pay $33 because we stayed more than the one week period they gave us upon entry. Until now they have refused to renew our permit to stay in Lebanon as refugees.

“I left my husband, my three sons and their wives behind in the camp. They said, at least here we have our own place, where are we going to stay in Lebanon? I’m staying at my sister’s; unlike my family I’m used to the situation in Lebanon. I grew up in Burj al-Barajneh camp. My married sons didn’t want me to leave but I couldn’t remain for one more day in Syria.

“My sister who has a house here in Lebanon called from Benghazi [Libya], her permanent residence, and told me, you better leave Syria now. My sister in Libya told me about her experience during the time [Muammar] Gaddafi was shelling areas that were revolting, and suggested Assad will do the same. In the camp our cars were hit and torched, bombs sometimes fell next to our building, and sniper bullets hit our balconies. Our daily life became full of fear and we were worried we might get killed accidently; that’s why we had to flee.

“Two days before we decided to leave we were at our relatives’ house when a bomb fell on the building next to us. We felt the bomb; it felt as if the apartment fell on us. Unconsciously, we found ourselves among others on the street running in all directions. The building was chopped in half by the bomb; it was a miracle that saved us, and after that night I decided to escape to Lebanon.

“Our camp became empty of all the basic necessities: UNRWA shut down the clinic and the doctors who used to operate there disappeared. Food stores are full of empty shelves. We were left with nothing but fear.

“There was only one good man, a pharmacist, he took his stock from the pharmacy and set up a first-aid station in a room in his apartment. He was treating people from his own supplies, and he gave us formula milk for our six-month-old girl and a few diapers. But it was only so much this pharmacist could do; there were severe cases he couldn’t treat — like broken bones or shrapnel wounds. These had to be attended to at a hospital; many injured people refrain from going to governmental hospitals.

“At one point aid was delivered to us by some political factions from the camp: bread, grains and lentils, but it stopped. Water stopped running in our taps and electricity has been completely cut off for two months.”

Back to Syria

The Massnaa crossing point, on the Lebanese-Syrian border, has been a hectic spot for refugees. In recent days, the border security authorities have called on the Lebanese army for reinforcement to control the refugees fleeing Syria.

Although most of the minivans here are bound for Lebanon, some are packed with Palestinians traveling back to refugee camps in Syria. These Palestinians have been unable to find assistance in Lebanon, so they have no option than to return to Syria, despite the ongoing violence there.

The Electronic Intifada approached one Palestinian family at the Massnaa crossing point: a father, his wife and their 10-year-old daughter. The father, who was in his 30s, said: “We are going back to Yarmouk [in Syria]. We stayed for 15 days with relatives and had to pay $33 each. While we were in Lebanon we went to the UNHCR office and they told us it’s not their responsibility to aid us. The UNHCR said, go to UNRWA.

“When we did they [UNRWA] said we have to register and wait: after we registered, we were told there is not enough money to cover Palestinian refugees who are not from Lebanon. At the UNRWA office it was clear that they were telling us we were on our own.

“Inside Yarmouk, there is no fighting but we get shelled from both sides fighting in the surrounding districts. I left my grocery store with empty shelves and spent all the money we had in Lebanon: an expensive place where we can’t afford to stay any longer. It’s better for me and my family to return to Yarmouk; there we might sleep with the sound of explosions and with empty stomachs but we know our dignity is untouched.”

No funding

An UNRWA employee, speaking on condition of anonymity, told The Electronic Intifada: “Through my work assessing the situation of the Palestinian refugees from Syria I came across an incident three days ago. There was a new wave of refugees from Syria who settled in a school in the border village of Majdal Anjar. At the school there were families of Syrian refugees and three Palestinian families from Syria.

“I was at the school when a Danish NGO [nongovernmental organization] arrived to distribute aid to the refugees; to each Syrian family they gave a relief kit made from food items, mattresses, blankets and $300. When the NGO workers started to leave the three Palestinian families from Syria asked why they didn’t get any of the aid that the Syrians got. The answer was, you are Palestinians, there is no aid for you in our campaign. The Palestinian families protested and said that they had run away from the same violence and bombing that the Syrian families escaped.

“Our UNRWA office is not able to aid the Palestinians from Syria because we only have a general fund for the Palestinians in Lebanon. The problem is when we appealed for the UNHCR to give us a special fund to aid the Palestinians from Syria, we know they have money at the moment, the UNHCR ignored our call.

“When I realized that the UNHCR had no intentions of aiding the Palestinians from Syria, I started advising the community leaders in the Beqaa region [of Lebanon] to call for donations directly from the people. We phoned rich businessmen and local NGOs and asked them to donate the bare minimum. We managed to gather enough for a one-time donation of food items, blankets and cooking pots.

“The only help the Palestinians from Syria are getting is from a few personal initiatives. The general picture is clear to see: the Syrian refugees are being taken care of on arrival by various NGOs and Lebanese political parties, but when the refugees are Palestinians they are left alone and this is because the case of the Palestinian refugees cannot be invested in politically.

“The discrimination is coming directly from the top, from the UNHCR which is the umbrella to the rest of aid agencies. Being an insider I know that the UNHCR at the moment has enough funds to cover the Palestinians from Syria: their ongoing refusal to allocate funds for the Palestinians is obvious discrimination.”

The Electronic Intifada contacted the UNHCR’s Beirut office but the agency declined to comment. UNRWA was also asked for an official comment but the agency did not respond.

Living in a boy scouts’ storeroom

Below the three floor building of a Palestinian cultural center in Saad Nayel, a town in the central Beqaa region, a small room previously used for storing boy scouts’ equipment, two families from Yarmouk camp have made their temporary home.

The cement floor of the room is covered with a thin blue plastic sheet to prevent Wakel and Ahmad, aged four and six, from cutting their bare feet while running around. In the small room there is a tiny bathroom being used as a kitchen as well. Sitting on a plastic chair in the dim storage room Khaledah Debsi, 46, a wife, mother and grandmother, greets us with a smile. With bitterness Debsi shares her story of being a refugee coming from a refugee camp.

“I’m originally from Akka [Acre] and my husband is from Haifa, Palestine,” she said. “It’s been one month since we left our house in Yarmouk camp. The situation was getting tense and dangerous when we left the camp. We left because the camp was dragged into the conflict and we were being harassed and provoked daily. Since we are Palestinians we had to pay a $12 exit fee, call it a bribe, at the Syrian border and a $33 entry fee at the Lebanese border. Add all this to the pricey transportation charges in these urgent times.

“At the moment we are illegally staying in Lebanon because our one-week permit is finished. If we decide to go back to Syria we will have to pay $33 penalty for each person, the six of us. Luckily we found this cultural center that took care of us and gave us this room, and two mattresses. Until now we have not seen any aid from any relief organization, but the kind people in the neighborhood gave us some help.

“Invisible” agencies

“There is a big shortcoming from the UNRWA, and the UNHCR, they have been invisible,” Debsi said. “There are Syrian families taking shelter at a public school: last week they received a complete aid portion and pocket money from an NGO but we were overlooked. I was refused aid, because I’m Palestinian. Clearly it’s discrimination against us, but we still cannot figure out why.

“As Palestinians from Syria our life was not easy but in the end we worked hard and made a living, and never felt the need for charity. I keep telling my grandkids and my son’s wife that this will end soon but time is passing by.

“My daughter-in-law is pregnant and the conditions we are living in are not fit for a pregnant woman. We still have relatives and family in Syria but they cannot afford to come to Lebanon. The past year has been a tough one because many people in the camp lost their jobs, and the few working are working to buy food for each day — if they don’t work they don’t eat.

“A month ago before we left the camp there was shortage in bread and vegetables and it was Ramadan. A week passed by without a crumb of bread. Shops had empty shelves; life became difficult.

“At first the camp stayed neutral. We didn’t want to take part in what was happening around us, but in the last three months the regime started harassing and attacking us in the camp. Therefore people in the camp had to defend themselves. Yesterday there was shelling on the camp; my sister sent me a message saying we are living a disastrous life.”

Abdullah Kamil, an organizer with the cultural center in Saad Nayel, said the plight of the Palestinian refugees from Syria has been overlooked by the media.

“According to our surveys we have 235 Palestinian families in central Beqaa — around 3,000 people. There are 250 families in al-Jalil camp, Baalbek; in the whole of Beqaa, there are 500 families. Our personal initiative is limited, more Palestinian families from Syria are arriving every day, and our modest efforts cannot cope with the growing numbers.

“Our one demand for the Lebanese authorities is to treat the Palestinians escaping from Syria just as they treat the Syrians fleeing to Lebanon. The Syrian is allowed to work, stay for six months for free, and it’s renewable. Why is this not the case for Palestinians?”

Living on crumbs

“Things are going to get worse for the refugees because winter is coming and it will be freezing cold in Beqaa,” Kamil explained.

“Buying diesel for heating is already expensive for us residing here. The few local NGOs that responded to our call gave us crumbs: we asked for 200 aid portions and we only received 50. We are trying to help these families but it’s only a little we can do, and the biggest player who is absent in these circumstances is the UNRWA. The only thing the UNRWA did was to count the numbers of refugees.

“This humanitarian case has been ongoing for two months, since Yarmouk was bombed, but the UNRWA are still counting numbers. We have been living in Lebanon for 65 years and we still have no recognition and rights from the Lebanese state.

“With regard to the Syrian issue we are being punished because we didn’t take sides and decided to stay out of the conflict. We learned from our bitter past not to get involved in internal Lebanese politics and conflicts. There are two main camps who are giving aid at the moment: the 14 March camp led by the Future party and the 8 March camp led by Hizballah, and we know in order for us to get aid we have to submit to the politics of these parties; we don’t want to affiliate with them. We know that once we sell ourselves to a political camp we will get aid, but it will come with a price.

“Each time we go to UNRWA they sing the same old song: there is no budget. Our next move is going to be a protest; we are going to gather the families, tell them to bring their mattresses and we’ll start sleeping outside the UNRWA office, maybe the problem will become visible to them, and they might start doing their job.

“We have sheltered two families in our cultural center, but we could only fit two families in the storage room. So far we have been managing to keep people calm and hopeful but when people get hungry and the cold winter hits we won’t be able to keep people sane.”

“No rights”

In the same dim room, Nisreen, the mother of Wakel, sits on a thin sponge mattress. Nisreen is expecting another child.

“My husband came to Lebanon before we did, he made sure he found a job then we followed after,” she said. “When we used to live in Yarmouk, I worked and my husband used to be an accountant for a company, but now he is working on a construction site. His boss knows that my husband is staying and working in Lebanon illegally so he pays him less than the normal wage that builders get, and this is the only source of living we’ve got at the moment.

“He is able to support us with 10,000 Lebanese pounds [$6] per day to buy bread, yogurt and eggs: meat and chicken are luxuries to us at the moment. In Syria we had some dignity since we could work in all sectors and we were able to buy our own apartment but we are shocked to find out that here in Lebanon, Palestinians have no rights and cannot work in any sector.”

Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have always envied the “privileges” that their compatriots in Syria enjoyed. The “privileges” that Palestinians in Syria enjoyed were basic human rights: the ability to work, own houses, equal access to healthcare and education, something Palestinians in Lebanon have been denied.

With the appalling situation in Syria, Palestinians are caught in crossfire and forced into displacement yet again.

Moe Ali Nayel is a journalist and fixer based in Beirut.