The Electronic Intifada 22 May 2024

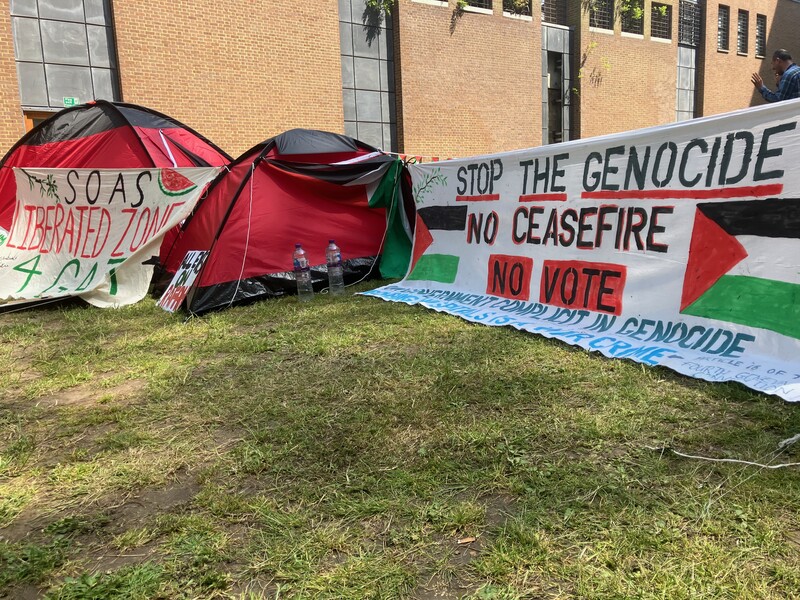

The SOAS encampment is small but in it for the long haul.

On a late-morning sunny May day in central London, students at the Gaza encampment in the grounds of the School of Oriental and African Studies were slowly stirring.

Occupying a small green space between university buildings across from the main entrance, the SOAS encampment comprises some 20 tents.

It’s small but remarkably organized.

At the front is an information desk with leaflets for passersby on the Palestinian struggle, on students’ demands, a schedule of upcoming speakers at the encampment, and so on.

Inside the camp, there are workshops for the students themselves on anything from Palestinian history and anti-colonial studies to self-defense and yoga, as well as specific areas set aside for studying and cooking.

The students there are determined to be in it for the long haul.

“This [encampment] is just one tactic,” said Brandao, a liberal arts undergraduate, who, like everyone else interviewed for this article, only gave a first name.

He was keen to emphasize that while the students protesting had specific demands from the SOAS administration to “stop profiting from the oppression of the Palestinian people,” the first priority was to keep the focus on what is happening in Gaza specifically and Palestine more generally.

“This is ultimately about ending the genocide, about Palestinian liberation and opposition to all the means by which the continued denial of Palestinian rights has been allowed to continue.”

Awakening moment

The UK student encampment movement started in late April and spread quickly to over 25 universities, from Aberdeen in the north to Sussex in the south.

“Inspired,” in the words of Brandao, by the US student movement, the UK’s encampments have been equally vocal but seen little by way of a police crackdown.

One source in London’s Metropolitan Police told The Electronic Intifada that while there was political pressure at the top to crack down on the encampments, the issue was widely seen in police circles as one for university administrations to deal with.

“Our role is to keep the peace, not inflame tensions,” the source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said.

From government ministers, however, there has been a greater echo of the official US response, most notably by invoking anti-Semitism. The first reaction by UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was to call in vice-chancellors of British universities to tell them to take “personal responsibility” for the safety of Jewish students.

And on 21 May, Michael Gove, a government minister and a “proud” Zionist, told a Jewish community center in North London that university protests against Israel’s genocide in Gaza were “anti-Semitism repurposed for the Instagram age.”

“The encampments which have sprung up in recent weeks across universities have been alive with anti-Israel rhetoric and agitation,” said Gove, who has been repeatedly criticized for holding Islamophobic views.

Brandao dismissed such comments as fear mongering by the government and typical of the “false conflation” of anti-Semitism with anti-Zionism.

“We are inspired by our Jewish comrades,” he said.

Another student, Seb, a history undergraduate, said the movement was all-inclusive and an “awakening moment” for large parts of a British population watching a genocide unfold in Gaza.

“Palestine used to be a predominantly Muslim issue in the UK,” she said. “Now all walks of life are represented, and people are beginning to realize, and object to, the UK’s complicity with Israeli crimes.”

Agitators

Generally, said Brandao, the public reception to the encampment at SOAS had been “incredible.”

While he was speaking, a woman approached the information desk to ask if students needed water or other supplies, an offer that was politely declined.

Inside the encampment, meanwhile, A.B., a physical therapist who volunteers their time, led an exercise workshop for the students focused on “nervous system control and strength building,” offering training on how to maintain physical and mental discipline if confronted with agitators or riot police in demonstrations.

There have been some isolated skirmishes at university encampments in the UK, notably at Oxford University, but nothing on the scale seen in the US.

Instead, Britain’s GB News, a Fox-like media outlet, treated viewers to footage of Suella Braverman, Britain’s erstwhile home secretary, being roundly ignored by Cambridge University students at their encampment. Remarkably, Braverman – who, while she was in office, described mass protests in London calling for a ceasefire as “hate marches” and wanted them banned – tried to present her visit as a free speech issue, a position for which she was later taken to task by another Cambridge student.A different movement

Braverman’s abject display was symptomatic of a generation gap that Ibrahim, a SOAS alumnus born in London but whose family is originally from Gaza, said made the current student movement different.

On the one hand, is a political class of “mediocrities,” well-versed in sound bites, but unable to handle substantial challenges and with little knowledge outside their own political interests.

On the other, is a young generation facing broad existential threats, from climate change to growing economic inequality, that has been forced to tackle such issues head on, both intellectually and practically, and which sees Palestine as symptomatic of an “old and corrupt colonial” order.

“This [movement] is run by youth, who saw the war crimes committed in Afghanistan and Iraq, who grew up with the Islamophobia of the ‘War on Terror’,” Ibrahim, who said he had lost 31 distant relatives during the genocide in Gaza, told The Electronic Intifada.

Students, he said, were determined to instill substantial change, reflected in the demands of the university administration.

These fall into several categories, including that universities divulge their financial investments, largely drawn from student fees, divest from any companies – including Barclays Bank, Microsoft, Accenture, among several others listed in leaflets handed out at the encampment – that are “complicit in Israel’s denial of Palestinian rights,” and boycott Israeli academic institutions, like Haifa University with which SOAS has a partnership, and which cooperates with the Israeli state in the violation of Palestinian rights.

There have been some small successes. Cambridge University has agreed to negotiate with students over their demands, while the University of York has announced it would divest from arms companies.

These fall far short, however, and students at the SOAS encampment said they were prepared for the long haul.

“We are not intimidated,” said Brandao. “And we are not seeking permission.”

Seb echoed the sentiment and said students were prepared to continue regardless of how they are portrayed.

“There is no such thing as ‘acceptable’ protest,” she said. “Disruption is part of protest.”

Ibrahim, meanwhile, said he was confident that an inflection point had been reached from which there was no turning back.

Recalling remarks in November by Jonathan Greenblatt, head of the pro-Israel Anti-Discrimination League in the US, he fully agreed – “I can’t believe I am agreeing with this man” – that supporters of Israel was facing a “major” generational problem.

“Zionism will never recover from this moment. It has lost our generation. It will lose the next generation. And the old generation will die.”

Omar Karmi is associate editor of The Electronic Intifada and a former Jerusalem and Washington, DC, correspondent for The National newspaper.