The Electronic Intifada 23 April 2020

With schools closed, Gaza’s children have to follow their lessons over the internet.

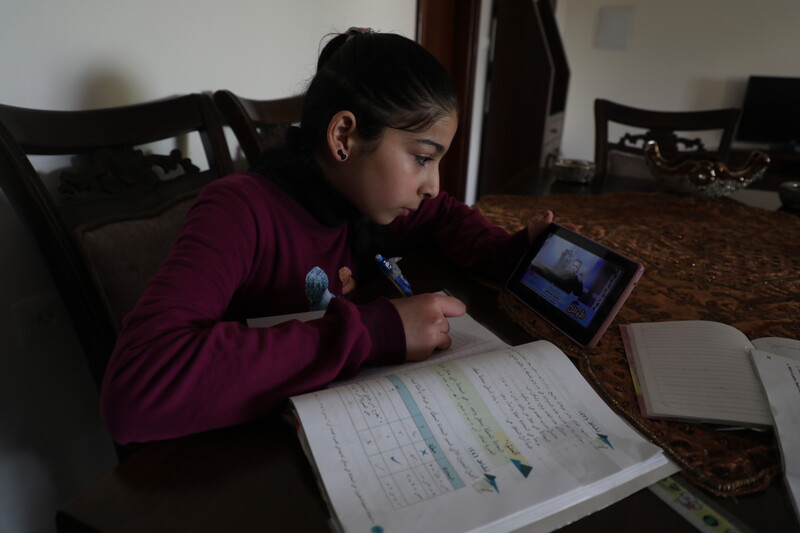

The Electronic IntifadaRaya Nofal finds it hard to attend classes over the internet.

“I don’t have a tablet,” the 11-year-old said. “My mother gives me her phone. But sometimes she gets a call and that interrupts our lessons. At other times, I can’t focus because the internet is slow.”

Raya’s experience is shared by numerous pupils in Gaza.

Schools have been closed since March in an attempt to halt the spread of the new coronavirus. While teachers have been giving lessons online, participating in them has been difficult for children who do not have adequate equipment.

As Raya’s father has been unemployed for the past two years, her family cannot afford to buy her a computer or other electronic device suitable for e-learning.

The problems have been compounded by frequent power cuts in Gaza.

Aya and Nisreen Saad are aged 10 and 15. Most mornings they are unable to follow classes on the internet as there is no electricity available.

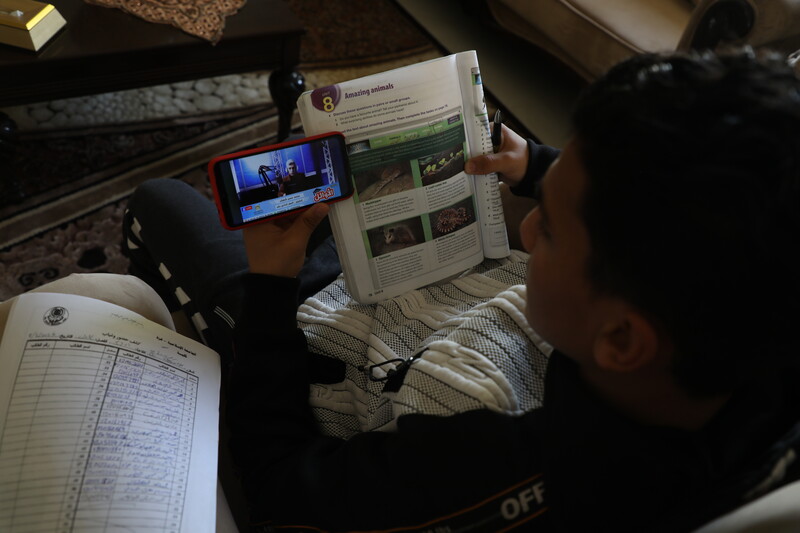

Furthermore, they do not have their own phones, tablets or computers. Both have to use their mother’s mobile phone.

“At first we thought that the children might enjoy following their lessons on the internet,” said their mother Iman. “Now I am upset that they are experiencing such difficulties because of poverty. E-learning might work in other countries but Gaza isn’t a suitable place for it.”

3G blocked

Children relying on phones, rather than computers, are at a particular disadvantage.

As part of the full blockade it has imposed for 13 years, Israel prevents Gaza from developing a third-generation mobile phone network.

Securing good quality internet access with a mobile phone is difficult in Gaza.

The Electronic IntifadaIt is, therefore, rare for people in Gaza to have good quality internet access on their mobile phones.

OCHA, a United Nations monitoring group, has found that the Palestinian education services were not prepared to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Both the occupied West Bank and Gaza did not have enough tools in place before the pandemic for pupils to be taught remotely. An additional complication, according to OCHA, was that the education ministries in the West Bank and Gaza could not agree on the content of e-learning programs.

Almost half of Gaza’s two million inhabitants are below the age of 18. And growing up in Gaza was already a major challenge before the COVID-19 restrictions were imposed.

As Gaza has been subjected to three major Israeli assaults since December 2008 – as well as a number of shorter offensives – its children have experienced more trauma than their peers in almost every other country.

In a 2018 report, the UN children’s agency UNICEF stated that approximately 300,000 children in Gaza need psychological support and other forms of protection.

“Nightmare”

Going to school has provided Gaza’s children with an important sense of routine, with teachers lending a helping hand to pupils with psychological problems. To give proper help, the teachers actually need to be in the same room as their pupils – not trying to hold classes over the internet.

Although Gaza has a radio station focused on education, such facilities are no substitutes for schools.

The Electronic Intifada“For Gaza’s students, school is not only a place for being educated,” said Muhammad Ayyash, who teaches science at a Gaza City school run by UNRWA, the United Nations agency for Palestine refugees. “It is a place for easing their stress. Staying at home will affect them negatively.”

The situation is not any better for students in higher education.

Aya Awni, 21, is studying nutrition and public health at the Palestine Technical College in Deir al-Balah, a city in central Gaza.

Not having a smartphone or computer of her own, she has had to borrow a friend’s laptop to undertake research and complete assignments. As she can’t use that laptop all the time, Awni has been unable to submit some of her coursework.

“It is a nightmare,” Awni said. “I always feel anxious.”

Her teacher Ayman Abu Zaina asked that students without computers write their assignments by hand and then send him photographs of their work with smartphones. The problem, however, is that quite a few of his students do not have a smartphone.

He has found that only 60 percent of his students have submitted assignments since the COVID-19 restrictions were introduced.

“University students all around the world have smartphones,” he said. “It is different here in Gaza because of poverty.”

Ola Mousa is an artist and writer from Gaza.