The Electronic Intifada Beirut 29 October 2013

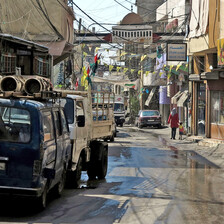

Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in March 2012.

APA imagesThe family of an ill two-year-old girl in a Palestinian refugee camp in northern Lebanon says the child’s life is in danger because of cuts to international aid.

The UN agency for Palestine refugees, UNRWA, announced a budget shortfall of more than $8 million in July. The result of this funding gap is that it has severely reduced emergency assistance — particularly aid for paying rent — to residents of the Nahr al-Bared camp in northern Lebanon (“Nahr el-Bared: Do not test our patience,” Al-Akhbar English, 21 July 2013).

Refugees from that camp have stepped up their protests against the cuts. On 11 October, they held a “day of rage,” which included demonstrations outside UNRWA offices in Beirut.

Directly affected

Amira Ishtawi, two years old, is directly affected by the service cuts, according to her family. Amira was diagnosed with an immune system disorder at the age of eight months.

Her family says she needs two shots every twenty days at a cost of $1,600. These costs were previously covered by UNRWA. But after its emergency aid program to Nahr al-Bared was suspended in September, the agency stopped covering them.

Today Amira’s family and their friends make calls at the mosque in Nahr al-Bared and have published a petition online asking for donations so the girl can receive her shots on time. If left without adequate treatment, her condition could be fatal. Ziad Ishtawi, Amira’s grandfather, said that her health had recently deteriorated as a result of missing her treatment for seven days.

Ziad Ishtawi, a 59-year-old well-known as an activist within the camp, noted that UNRWA’s emergency assistance provided hospitalization coverage. Those suffering from heart disease and kidney complaints would be the most affected by reductions to this aid, he said. Ishtawi knew of 35 patients requiring dialysis. “Some of those need up to three sessions per week at the cost of $300 per session,” he added.

Since the camp was destroyed by the Lebanese army six years ago and approximately 27,000 residents displaced, an estimated 600 to 700 of the 4,000 families living in Nahr al-Bared have returned. Conditions are grim: the main shelter for many of these families are iron containers — of the type used in cargo ships — stacked together to resemble a two-story building block. Residents call these makeshift homes bareksat — barracks.

Those who remain displaced have had to find shelter in Lebanon’s other refugee camps.

There are more than 436,000 Palestinians registered with UNRWA in Lebanon, where Palestinian refugees are barred from owning property and working in most professions, resulting in dire economic conditions.

Ishtawi described UNRWA’s cuts as a “final bullet to a camp in its death throes.”

“No choice”

Margot Ellis, UNRWA’s deputy-commissioner general, wrote to community leaders of Palestinian refugees in northern Lebanon last month.

“Faced with insufficient funding for the emergency relief assistance, UNRWA had no other choice but to prioritize which services should be retained and which services had to be reduced,” Ellis stated. She attributed the shortfall in funding to how “regional situations have shifted donors’ attention elsewhere.”

According to Ellis, UNRWA had decided to cease providing rental assistance to 1,000 families but would continue to give such aid to some 2,000 families. A review by the agency had concluded that many of the 1,000 families were not currently renting accommodation.

Ellis also stated that funding by two unnamed European countries had made it possible to “assist the kidney dialysis patients for the coming six months with $50 coverage for each session.” She added that more than 50 percent of the reconstruction budget for Nahr al-Bared has been financed and that “approximately 2,500 families should have returned by the end of next year.”

Chronic budget shortfalls

However, the picture may be more complicated than donor countries not making good on their pledges, which has been a chronic and anticipated problem for UNRWA.

The agency’s program budget for 2012-13 shows that UNRWA had a funding gap in 2010 and projected that it would also have gaps for 2011 and 2012. “UNRWA is operating in a financial situation where the disparity between budget, income and expenditure has become chronic,” the document states.

According to the document, UNRWA recognized that it would have budgetary problems as a result of the current global economic climate.

However, UNRWA did not plan to reduce its budget despite the anticipated shortfalls.

The agency’s allocation of resources is also worth scrutinizing. Almost 75 percent of its budget, or $675 million, went to pay staff salaries this year. Salary expenditure has gone up from $400 million in 2008 to more than $502 million in 2013. Yet its spending on medical supplies in 2013 is approximately the same as it was in 2009.

Beirut sit-in

UNRWA’s deputy general Ellis complained about protests undertaken by Palestinian refugees in Lebanon recently. Closures of UNRWA offices due to protests would delay the process of bringing refugees back to Nahr al-Bared, she stated.

But protesters in Beirut have insisted that they were not preventing UNRWA employees from working.

A sit-in tent was erected in the Lebanese capital — across from UNRWA’s office, which overlooks Sabra and Shatila, two Palestinian refugee camps synonymous with a massacre perpetrated by a Christian militia allied to Israel in 1982.

Sitting outside the tent on four plastic chairs and a coffee table, Salim Abeldaziz Salameh, 58, said that he was only blocking access to the entrance of UNRWA’s offices.

“The UNRWA employees can still enter from the back,” he told a paramedic from the Palestine Red Crescent Society who came to check on the protesters. “We don’t intend to shut down the whole UNRWA building yet. If we did, the lives of thousands of refugees will be affected and that’s not our goal.”

Salameh had already spent three weeks in the protest camp when the “day of rage” took place. He said that refugees intend to escalate their protests, underscoring that they would remain peaceful.

PA “ineffective”

Ziad Ishtawi said that the protests have been partly motivated by the slow pace of reconstruction in Nahr al-Bared. He also expressed frustration with the lack of support that refugees have received from the Palestinian Authority leadership in the occupied West Bank.

“The Palestinian Authority has been ineffective, putting no pressure on UNRWA, and only releasing shy statements which deepen doubts and exacerbate fears in our community,” he added.

Ishtawi’s family hails from Nahef, a village near Akka (Acre) in the Galilee region of what is now called Israel. “If it was up to me I would leave for Palestine now with the clothes I’m wearing, not looking back or taking anything with me, because there is no dignity and identity for a human without a homeland,” he said.

Moe Ali Nayel is a freelance journalist based in Beirut, Lebanon. Follow him on Twitter @MoeAliN.