The Electronic Intifada 15 July 2017

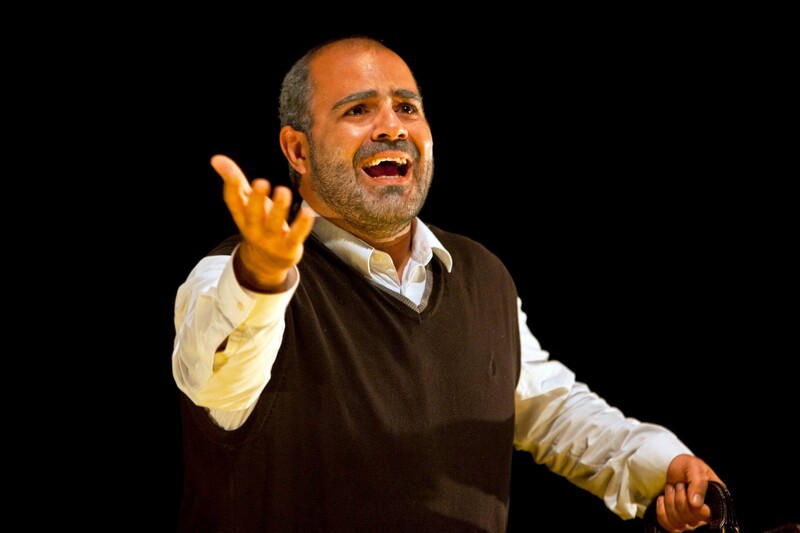

Amer Hlehel performs as Taha Muhammad Ali at the Young Vic. (David Sandison/Young Vic)

Taha, written and directed by Amer Hlehel, Young Vic, London

Amongst the 1960-70s generation of Palestinian writers dubbed the “poets of the resistance,” Taha Muhammad Ali, who died in 2011, is perhaps least known to an English-language readership.

He is often overshadowed by better-known, more frequently translated colleagues Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim; this is despite a critically praised volume in translation (So What: New & Selected Poems, 1971-2005, Copper Canyon Press, 2006, and a wonderfully tender and detailed biography (Adina Hoffman’s My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness, 2009).

It is to be hoped, then, that the international performances of Amer Hlehel’s moving play, simply titled Taha, help raise the profile of this talented poet and his strange, sometimes sad, but ultimately inspiring life story.

Hlehel’s play, a one-man performance which he both wrote and acts, has enjoyed a run at London’s Young Vic theater which was met with rave reviews and standing ovations. Previous shows of the English version – adapted from the Arabic original, which Hlehel has been touring since 2014 – include Washington, DC, and Hlehel will go from London to 11 days at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Alongside the sensitive, understated direction by Amir Nizar Zuabi of the Haifa-based ShiberHur theater company, Hlehel’s performance itself is one of the reasons for Taha’s success so far.

Alone on stage for the entire length of the play, he manages to convey the extraordinary range of emotions and events that constituted the poet’s life with strength and simplicity. It is not too much of a stretch to wonder if Hlehel and Taha Muhammad Ali’s shared status as Palestinians living in the State of Israel – with all the oppression and contradictions that this entails – gives the writer/actor greater insight into his subject.

Portrait of life in 1930s Palestine

In the first part of the narrative, set in Muhammad Ali’s home village of Saffuriya in the Galilee, shortened throughout to the local pronunciation of Safuri, Hlehel captures the joy of a clever boy exposed to books and the wonders of the Arabic language. This is a portrait of life in a thriving town in 1930s Palestine.

“I was very, very happy,” Hlehel’s Taha says, and we absolutely feel his happiness and satisfaction.

But he also conveys the harshness of life growing up in a poor family, in which acquiring a pair of shoes is a major life event. And he evokes the ebullient, entrepreneurial spirit of the young Taha, who from an early age supported his mother and siblings when his father, affected by polio in childhood, could not work.

Quite outstandingly, the lone Hlehel draws the audience into the real terror of the teenage Taha, herding a group of lambs he hoped to sell at the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, as he comes under attack from a Zionist warplane.

This attack leads to the terrified flight of most of the population of Safuri, across the Palestinian border into Lebanon and, as Hlehel’s script describes, the sea of blue tents supplied by the United Nations to the thousands of refugees who, like Muhammad Ali’s family, arrived in the town of Bint Jbeil.

Unusually, though, Muhammad Ali’s family managed to get smuggled back into Palestine and, through bribes and pleading, obtain residency papers from the new Israeli state. They could not return to Safuri, though: the village was almost entirely destroyed; Israeli farms were set up on its land, and a forest planted in an attempt to erase its Palestinian history.

Eventually, the family settled in the city of Nazareth, which remains the most populated Palestinian Arab city within Israel. Taha’s entrepreneurial skills were again all that supported the family: he became a “Muslim selling Christian memorabilia to Jews,” running a souvenir stall in the Old City, close to the tourist and pilgrimage sites associated with the life of Jesus.

Conflict and poetry

Hlehel’s skilful writing, developed in a workshop at the Sundance Institute, not only conveys the narrative of Muhammad Ali’s story, but also the complex, interwoven strands of love, longing, family conflict and poetry that marked his life.

The audience’s hearts ache for the young man separated from his cousin Amira, whom he had loved since he was told at her birth that their families hoped they would marry. The pathos of Hlehel’s performance is heartbreaking, although the script also perhaps understates the eventual role of Muhammad Ali’s wife Yusra, with whom he later found domestic happiness, as highlighted in Adina Hoffman’s biography.

But we also feel his underlying urge to write, to connect with words and language, and to explore these instincts with like-minded people.

From the early days of his family’s life under Israeli rule, Taha devoured Arabic literature and poetry, later hosting salons in the 1960s that included major figures in the Palestinian press of the day alongside the great poet Mahmoud Darwish and the Druze poet Samih al-Qasim, Ali’s lifelong friend.

It was al-Qasim who, late in Muhammad Ali’s life and after the latter had experienced long periods in which he could or would not write, brought him back to the attention of Arabic-reading audiences, including a performance in front of the Syrian romantic poet Nizar al-Qabbani.

Hlehel’s play maintains this constant thread of poetry through Muhammad Ali’s life both by including events in the narrative itself and through using poems that evoke and embody particular moments and themes.

An especially strong example is when Hlehel utilizes a poem in which Muhammad Ali refers to the land of Palestine as a “whore,” berating her for submitting to Israeli forces, to capture the young man’s ambivalence about returning from Lebanon, leaving behind family including his beloved Amira.

It is, perhaps, this ambiguity which makes Taha Muhammad Ali such a compelling and yet challenging subject. From the boy with great dreams of both business success and poetic fame, to heartbreak and a life selling knick-knacks to tourists, and yet eventually attaining that fame, we feel the sometimes contradictory pulls of love, land, art and family.

But Hlehel’s script and performance bring these tensions sharply yet tenderly to life. His audiences are privileged to witness a profoundly human story of the impacts of the historic events that have swept across Palestine over the past century.

Sarah Irving is author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone.