The Electronic Intifada 25 July 2017

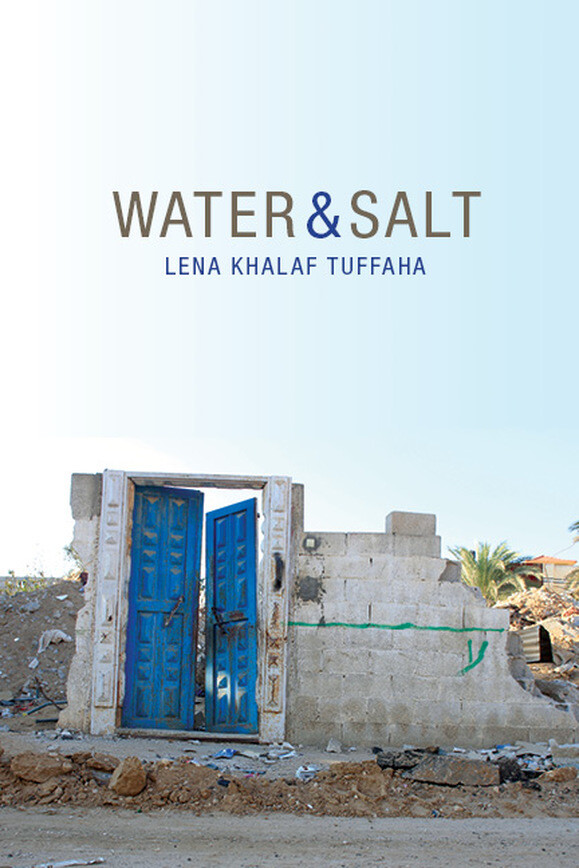

Water & Salt by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Red Hen Press (2017)

In the poem “Dhayaa’,” Lena Khalaf Tuffaha firmly establishes that her work is written in her second language.

The poem begins with the line “In my language,” before clearly laying out that the language to which Tuffaha refers is Arabic. The ensuing lines contrast the feeling of dhayaa’, the Arabic word for loss, against the terser English term and compare it with a sensation of being:

a wide-open cry,

a gaping endless possibility

Certainly, though, there is nothing in Tuffaha’s skilled use of English in this book of poems that would suggest it is not her mother tongue.

Whether shaping her words to deliver nostalgia, pain, humor or anger, a good proportion of the work in Water & Salt, her second collection of poems, places Tuffaha in a growing tradition of female Palestinian-American poets who blend motifs of family, homeland, politics, food and love to present rich, heartfelt images of diaspora life.

The obvious comparison is with Naomi Shihab Nye (indeed, Tuffaha chooses to quote from Nye at the start of this volume), but points of contact with the likes of Nathalie Handal and Suheir Hammad also emerge.

Language, identity and pain

That’s not to say that Tuffaha doesn’t have her own voice; she does, and in the best works of this collection it rings through loud and clear.

The aforementioned “Dhayaa’,” for instance, manages to pack considerations of language, identity and pain into a short poem, and also combines a kind of self-conscious self-orientalization – a use of “exotic” motifs such as the dervish – with nods to references to the Western literary canon.

The most obvious of these is the phrase “widening gyre,” from William Butler Yeats’ famous work “The Second Coming,” written in the wake of the horrors of the First World War and with its own Palestinian reference in the image of an incarnated Messiah as a “rough beast … slouch[ing] towards Bethlehem.”

Tuffaha also has a particular talent for evoking, and giving a subtly political edge to, nostalgic images of home and family.

These are often particularly female-centered, as in the warm, poignant poem “Grandmothering,” which describes a young girl having her hair combed and braided by her teytah, the informal Arabic word for grandmother. Family affection is irrevocably tied, through the use of the language of youth and age, and familiarity and loss, with a sense of longing that goes beyond the personal.

The opening poem of the collection, “Upon Arrival,” especially succeeds at this delicate balancing act, pairing a loving description of a grandparental home emptied, presumably during the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine, with a repeated set of terse border control instructions: “You will need to state the reason for your visit.”

Facing unending fear

Tuffaha is not just Palestinian in origin, however. She is also Jordanian and Syrian, and as a result the pain and anger she has channeled into her poetry also stem from events in these neighboring countries.

Nostalgia and family run tenderly through the poem “Damascus Dowry Chest,” in which the carved wooden souvenir of a long-ago wedding contains:

love letters penned in hasty ink from far-flung battlefields

huddle in the shadow of its musky walls

The reader is meanwhile reminded of the many wars which have been imposed on the modern Middle East.

In “Wasta” (nepotism), however, Tuffaha resorts to humor, conjuring up bitter, ironically comic images of the effects of relatives employed, being educated or managing to dodge taxes thanks to personal connections.

In the poem, an uncle with the “mini shawerma empire” avoids paying his taxes, while judging that it’s better to have a failing student pursue business, even if their scholarship is undeserved, than “conduct ‘business’ in the shadows.”

But, the poet pleads with comic severity, “what cannot be excused/and should not be tolerated” is for the corrupted Jordanian or Syrian governments to have been allowed to choose the muezzin who performs the call to prayer.

The “morose and grumbling/bray of his call,” she complains, is damaging to her faith, to the point where she prays “only for the mercy of silence.”

Colonialism and corruption

The overlapping of these identities, however, and of the colonialism and corruption to which Palestine, Jordan and Syria have all been subject in their different ways, is most poignantly conveyed in “Mountain, Stone.”

Here, Tuffaha enjoins Arabic-speaking parents to take the utmost care in naming their offspring.

The poem cites a series of cases: Egyptian and Syrian women killed by their governments’ security forces, a Syrian boy tortured and killed by Bashar al-Assad’s police, a Palestinian girl jailed by Israel and the four boys of the Baker family killed by an Israeli missile while playing football on a beach in Gaza City three years ago.

The work bears the agony of parents who, in bringing children into the world, face the unending fear that they will meet violent ends at the hands of unjust regimes. Better, Tuffaha suggests, to name them after the impermeable, untouchable, but lifeless strength of rocks and hills.

Not all of the poems in this collection work so well; some tread overly familiar ground in the ways they convey images of Israel’s oppression of Palestinians or the hypocrisy of the US media.

The “Apache helicopters and F-16s” and the “bombing civilian neighborhoods” by “superpowers,” for instance, may tell a literal truth, but they are also an inescapable feature of amateur writing on Palestine.

But overall this volume, with its evocative and moving explorations of identity and loss, establishes Tuffaha as an emerging voice in Palestinian-American literature whose works are well worth seeking out.

Sarah Irving is author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone.