The Electronic Intifada 19 November 2009

The biography of place lost begins with the village Saffuriyya, which was perched atop a hill in the Galilee. Ali’s childhood there was difficult but idyllic. His father was hobbled by a bout of polio and unable to work, leaving his family poor. Ali, who was born in 1931, attended school for only four years before he began to support his parents and their growing brood. At a time he should have been learning math, Ali worked as a businessman, selling eggs in Haifa.

Eventually Ali, a savvy entrepreneur, ran a kiosk from his family home. He built a small but bustling business, with an eye turned towards his fiancee, Amira, betrothed to him since birth, “whose trickling laughter and graceful gait,” Hoffman writes, “had entered his bloodstream so profoundly that she almost seemed to be part of him …”

Amira’s presence, along with the gentle Galilee, softened the rough contours of Ali’s early life. The landscape later conjured in Ali’s poetry and recreated in Hoffman’s book, teems with life and seems somehow different from the surrounding world, almost magically so. Hoffman writes:

“The thorns themselves seemed to smell sweetly there, and though he couldn’t say which perfume belonged to what plant — or explain how he knew the difference between the fragrance of a Nazareth sage bush and a sage bush with its roots in the soil of Saffuriyya — the boy was convinced that he could tell in his nose when he’d crossed the border …”

Saffuriyya sat on rich land that yielded mounds of fruit including “the most sought-after pomegranates in the whole Galilee.” Saffurriyya was a “village of the Quran, of epic tales and colored Damascene or Cairene prints of their heroes …” And most importantly, Saffuriyya was a thread weaving Ali and his family through the fabric of Palestine.

But the cloth was torn on a July night in 1948 when Israeli forces bombed the village. Ali and his family fled to Lebanon. There the teenaged Ali hawked goods in a refugee camp until the spring of 1949, when he and his family returned to freshly-named Israel. After sneaking over the border under the cloak of night, they settled in Nazareth, less than 10 kilometers from the remains of their village. Ali opened the kiosk that later became one of the two souvenir shops he owns today.

Though his own career as a poet began late in life, Ali’s store in Nazareth was a frequent meeting place for important Palestinian literary figures, including Michel Haddad amongst others. At this point the book becomes, as Hoffman calls it, a “kind of group portrait.” Hoffman explains, “Taha is hardly the only artist in this story … To understand Taha and his place in Palestinian and indeed Arabic letters, it’s crucial to be conscious of the range of personalities that have surrounded him over the years.”

While the reader occasionally loses Ali in My Happiness, the book compels the reader to search out his poetry — available to English-readers in So What: New and Selected Poems 1971-2005 translated by Peter Cole, Yahya Hijazi and Gabriel Levin — and there he comes into full view.

Ali’s poems, each powerful in its own right, resonate most deeply when taken as a whole. When considered in such a gulp, recurring themes and images take on new dimensions. In “Ambergris,” published in So What, he writes:

This land is a whore

holding out a hand to the years …

Our land makes love to the sailors

and strips naked before the newcomers …

there seems to be nothing that would bind it to us,

and I — if not for the lock of your hair,

auburn as the nectar of carob …

Your braid

is the only thing

linking me, like a noose, to this whore.

Here, hair chains the narrator to a land that will betray and suffocate him. But in “The Place Itself, or I Hope You Can’t Digest It,” also published in So What, hair appears again, this time as a thing of comfort:

And so I come to the place itself …

Where are the bleating lambs

and pomegranates of evening —

the smell of bread

and the grouse?

Where are the windows,

and where is the ease of Amira’s braid?

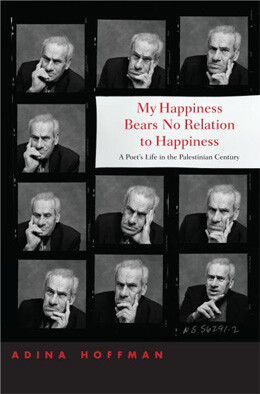

In both Ali’s poetry and Hoffman’s biography — which Booklist recently named one of the top ten biographies of 2009 — Ali’s deep, and deeply complicated, connection to the land is highlighted. Hoffman, in turn, takes great care to explain the historical circumstances his ambivalence is born of. My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness should be considered, then, a crucial complement to — but not substitute for — Ali’s work. Much as Ali’s poems are in tune with each other, so does Hoffman’s biography work in harmony with Ali’s writing, life and times.

Mya Guarnieri is a Tel Aviv-based journalist and writer and a regular contributor to The Jerusalem Post. Her work has also appeared in Outlook India —- India’s equivalent to and subsidiary of Newsweek —- as well as The National, The Forward, Maan News Agency, Common Ground News Service, Zeek, The Khaleej Times, Daily News Egypt and other international publications.

Related Links

- Purchase My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness on Amazon.com