Electronic Lebanon 19 June 2009

A map of Nahr al-Bared refugee camp with the different areas marked.

The three-month-long war between the Lebanese army and Fatah al-Islam militants in the Palestinian refugee camp of Nahr al-Bared in northern Lebanon ended on 2 September 2007. While the Lebanese army has allowed displaced residents to return to some parts of the camp, the fate of other parts of the camp still under the army’s control remains unclear.

Nahr al-Bared camp consists of an “old” and a “new” camp. The original or “old” refugee camp was established in 1949 on a piece of land 16 kilometers north of the Lebanese city of Tripoli. In 1950, the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) started to provide its services to the camp’s residents. Over the years, population density in Nahr al- Bared rose drastically while refugees who could afford it, left the boundaries of the official camp and settled in its immediate vicinity. This area is now referred to as the “new camp” or the “adjacent area” and belongs to the Lebanese municipalities of Muhammara and Bhannine. While the residents of the new camp benefit from UNRWA’s education, health, relief and social services, the agency has no mandate for the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure and houses in this area.

Since the fighting in the camp ended nearly two years ago, most of the so-called “old camp” has been bulldozed and reconstruction is set to begin within the next month. Along the perimeter of the old camp however the ruins of more than 200 houses are still standing. They’re under the sole control of the Lebanese army, which still prevents residents from returning.

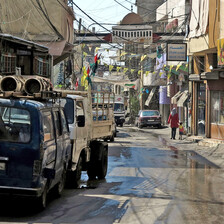

Area B’ of Nahr al-Bared.

In October 2007, approximately one month after the Lebanese army declared victory, the first wave of refugees was allowed back into parts of the new camp. In the following months, the army gradually withdrew from the new camp and returned the houses and ruins to their former residents. However, the handover wasn’t complete. At least 250 houses in the new camp, adjacent to the old camp, remain sealed off by barbed wire, controlled by the Lebanese army and inaccessible to its residents. These areas are now referred to as the “Prime Areas,” known among the refugees under the Arabized term primaat. They consist of A’-, B’-, C’- and E’-Prime.

Adnan, who declined to give his family name, works in a small shop in the Corniche neighborhood, adjacent to area E’. He has been waiting for the handover of the area by the army. “They tell you, ‘Next week, next month.’ But nothing happens. They say, ‘We first have to remove the bombs and the rubble, then we let people in.’ These are empty words. Nobody is honest. They constantly lie to us,” Adnan complained.

Temporary housing serves as the makeshift office of the Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Commission for Civil Action and Studies (NBRC), a grassroots committee heavily involved in the planning of the reconstruction of the old camp. Abu Ali Mawed, an active member of the NBRC, owns one of the 120 buildings in area E and has been waiting for its handover for 21 months. “The army once more says they’ll open the primaat, but first [the army] will need to [clear] them [of] unexploded ordnance devices and rubble. Where have the parties responsible for this work been in the past two years? Let us be honest: This area could be de-mined and cleared within just under a month!”

Ismael Sheikh Hassan, a volunteer architect and planner with the NBRC, said, “The main reason for the delays is the army. They haven’t taken the decision at command level to allow people to return until last month.”

Since the end of May, things have seemed to finally move forward. On 19 May, an UNRWA contractor started clearing rubble in area B’ and de- mining teams took up their work. UNRWA wrote in its weekly update on 3 June that its contractor had finished clearing rubble in areas B’ and C’. In a meeting among the Lebanese army, Nahr al-Bared’s Popular Committee, Palestinian parties and UNRWA on 2 June, the army announced its intention to allow the return of the residents of these two areas within two or three days. As of 7 June however the promise hadn’t been delivered.

Sheikh Hassan explained that the suspension was mainly due to delays in de-mining procedures and those related to miscommunication among the various structures of the Lebanese army. He expected them to open areas B’ and C’ in a few days. There are 40 houses in B’ and 60 buildings in C’ to be handed over. On 11 June, UNRWA announced that they were told by the Lebanese army that the handover of B’ and C’ would take place mid-month.

The army’s procedures have raised doubts. Abu Ali Mawed, the reconstruction commission member, asked, “How could they allow people last year to return to their burnt, looted and destroyed homes to save some of their belongings, if there were still vast amounts of unexploded ordnance lying around? They should have de-mined the area before letting people in. In the primaat, many houses aren’t completely destroyed, which facilitates de-mining. I suppose that the unexploded ordinance have already been cleared and de-mining is only used as an excuse for further delaying the handover.”

According to UNRWA, the army and the Popular Committee will be responsible for announcing and coordinating the schedules and logistics of families returning to the Prime Areas.

Destroyed houses in area E’.

Nidal Abdelal of the Palestinian political faction, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine shook his head: “So far, neither the Popular Committee nor UNRWA understand why the army doesn’t hand the primaat over so people can return. The Lebanese army sets dates [but doesn’t deliver]; this has happened four or fives times. And until today, minor problems in the details constantly prevent them from handing over the primaat.”

Abdelal points out that the persistent delays of the handover dates cause skepticism and worries among the refugees. “They even call UNRWA and the Popular Committee liars,” he says. “They tell people a date, then they postpone it. Then they set another date and again postpone it. In the end, the army controls the primaat and is responsible for their handover. They should eventually hand the areas over to UNRWA and the Popular Committee and let people return.”

Another camp resident, Abu Ali Mawed, compared the situation of displaced residents of Nahr al-Bared to that of southern Lebanese displaced during the summer war of 2006: “Israel dropped about one million cluster bombs in the south, but people could immediately return to their homes [once] the war was over. Why have we for two years not been allowed to return to our houses? … We asked these questions to the government, army representatives and politicians many times, but never got clear answers. They kept giving us lame excuses that were far from convincing.”

Besides the upcoming handover of areas B’ and C’, further questions need to be answered. For example: What will happen to the houses in the primaat once they’re accessible? These houses were assessed and will be stabilized and rehabilitated. If this isn’t possible and their owners agree, they’ll be torn down. An anonymous source with UNRWA believes that only a few homeowners will agree to the total destruction of their homes because other landlords have experienced that the Lebanese government doesn’t sign building permits for Palestinians to build in the new camp.

Currently unscheduled is the handover of areas A’ and E’. Sheikh Hassan of the NBRC says there’s speculation “that those areas will be opening in the upcoming months. However, there are no guarantees on this. E’ will definitely be opened first. A’ will be opened last.” Access to E’ seems to depend on the rubble removal and de-mining process in the adjacent two sectors of the old camp, because they’re still heavily contaminated with unexploded ordnance. According to Nidal Ayyub of UNRWA, the Lebanese army so far has “no plan to open [area] A’.”

However, the Lebanese army did have plans for the construction of an army base in Nahr al-Bared. On 16 January, the Lebanese cabinet decided to establish a naval base in the camp as well. Both plans concern mainly areas A’ and E’ and the coastal strip along the old camp. Just months ago, fierce protest to these plans was voiced by the camp’s residents and the government has reportedly dropped its plans. However, only when the Lebanese army finally makes clear its intentions for the handover of the remaining parts of the camp will residents’ worries be dispelled — or their fears for the future of Nahr al-Bared confirmed.

All images by Ray Smith.

Ray Smith is an activist with the anarchist video collective a-films.