Electronic Lebanon 22 May 2008

The “old” camp in Nahr al-Bared lies in ruins and remains off limits to the Palestinian refugees.

One year ago, on 20 May 2007, the fighting began between the Lebanese army and the militant group Fatah al-Islam in Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in northern Lebanon. During more than three months of fighting between the army and the extremist group, more than 47 Palestinian civilians, 178 soldiers and at least 220 militants were killed. More than half a year after the battle came to an end, only a fraction of its residents have been allowed to return. Those who have come back to the camp do so only to find that most of their houses have been reduced to rubble.

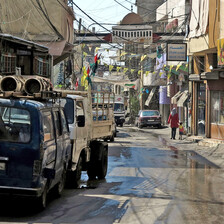

However, for most of the 30,000 Palestinians who once populated Nahr al-Bared, their return to the camp is still far off. As of late April, only between 1,500 and 2,000 families have been allowed to return to the so-called “new” camp that is located outside the core of Nahr al-Bared. The “old’ ” camp refers to the original site of Nahr al-Bared which is now completely destroyed and sealed off by the Lebanese army for, it states, “de-mining” purposes.

In February 2008, the Lebanese government approved a preliminary master plan for the reconstruction of the old part of Nahr al-Bared camp, jointly prepared by the Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Commission and the UN agency for Palestine refugees, UNRWA. According to this plan, reconstruction will begin on 15 August 2008 and should be completed by mid-August 2010. The plan states that the success of the prepared schedule is only possible if “the army allows immediate access to [the] old camp to commence the necessary de-mining, risk assessment and rubble removal and site leveling task[s] which need to be completed by 15 August 2008 to allow the beginning of construction on that date.” The plan, however, is “subject to further development and adjustment over the upcoming months until a final master plan is finalized.” Until now, no final master plan is in sight.

Many of those who have returned to Nahr al-Bared are currently either living in the ruins of their old houses or in garages. As an alternative, UNRWA has installed 300 prefabricated temporary housing units, made out of iron and plastic, in the northern end of the refugee camp, and concrete structures with metal roofs in the southern end of the camp, where relocated refugees have been living since last autumn. In mid-April, another 150 structures were built in the hills on the southern end of the camp.

Some of the prefabricated housing units in Nahr al-Bared.

In early March, 188 families who were living in schools in the neighboring Baddawi camp for the past nine months were relocated to the prefabricated housing units in the northern part of the camp. Families consisting of more than five persons received two of these units. Each unit is equipped with a sink, to be used as a kitchen, and a small bathroom. The latter, however, often don’t suit the needs of old or disabled people. The units have a ground level and an upper level accessed by an outside staircase. Because of their construction material, the noise is often unbearable for inhabitants of the lower units and when the upper platform is cleaned, the water runs down to the ground or leaks on the people on the lower level. The units on the top level already overheat during the day, and it is still only spring. Residents are concerned regarding the coming summer and the heat because electricity is only available for parts of the day and thus cannot constantly power fans to help cool the units.

In mid-April, those displaced people who have spent their last nine months in either al-Quds or Omar Bin Khatab Mosque or in Nahr al-Urdun, Ramle or Majdal schools in Baddawi Camp, were moved to the new housing units in the south of Nahr al-Bared. The conditions in these structures are better then at the containers near Abdi checkpoint. There is only one floor and way more space between these units. Also there, only two amps of electricity are provided to each unit there for a restricted amount of hours per day. However, the installed water boilers require five amps. So long as the army controls the area of the camp in which they formerly lived, and the reconstruction is delayed as a result, residents don’t know how long they must live in these substandard conditions.

On 31 March 2008, the Lebanese army granted access to residents of parts of two additional streets, Majles Street and Sahabe Street near the old camp. In the end of April, the building belonging to the Beit Atfaal al-Sumoud organization and a few other houses in the neighborhood were left by the army who occupied them for the past months. In most cases returning residents found that their furniture and appliances had disappeared. Also, frames of windows and doors as well as the doors themselves or bathroom fixtures have disappeared. In many houses, even the interior rooms not hit by rockets, grenades or gunfire were demolished. That which couldn’t be looted was vandalized or burned. Furthermore, in most of the houses, several rooms (if not the whole apartments) are black from the burning. Most of the fires were — as is often evidently clear — caused by the burning of furniture or by the burning of flammable liquids such as petrol. The latter was splashed on walls and left behind clearly visible stains. Looting, intentional destruction and arson are widespread, and in most of the cases were done within the weeks after the battle concluded. Camp residents observed their homes during and after the siege from the nearby highway — some even photographing the smoke coming from their houses after the siege had ended.

Cleaning up and repairing the newly accessible houses is difficult and tiring. The residents, who have lost most of their possessions, are often ill-equipped and have to clear endless masses of rubble, working room by room and floor by floor, using shovels, carts, hammers and their bare hands. There is basically no assistance towards this end by any aid organization in any way. Many of the houses are at risk of collapsing and in some cases unexploded ordnance, hand grenades or other explosives are found in the rubble. The wait for one of the few bulldozers in the camp to take away the rubble can take several days, as UNRWA bulldozers are not easily available and privately owned bulldozers are not affordable. Recovered metals are assorted and later sold. Children search through rubble for profitable items and are regularly chased away by the homeowners or Lebanese army soldiers.

Furthermore, the omnipresence of the Lebanese army and its security apparatus and the restricted access to the new camp creates serious problems for the refugees. The Lebanese army controls Nahr al-Bared through a net of occupied houses, checkpoints and patrols as well as through a bureaucratic permission policy. Agents from the army secret service monitor the camp by patrolling the streets during all hours. Houses, schools and even medical clinics are searched on the pretext of looking for hidden bombs. It is said that the number of local Palestinians collaborating with the Lebanese army is increasing as the security forces are especially recruiting young people. According to Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, the destruction of Nahr al-Bared is an opportunity for the Lebanese security apparatus is to extend its authority to the camp, a historically and politically significant move which breaks away from the Cairo Agreement of 1969 which forbids the Lebanese army from entering the Palestinian-controlled camps.

The just over three months of fighting last year between the Lebanese army and Fatah al-Islam is not generally perceived by many Nahr al-Bared refugees as a legitimate military battle but as a pretext to achieve political purposes. Many believe that the destruction of the refugee camp, previously an economic center for the neglected region of northern Lebanon in which it is situated (the poorest area in all of Lebanon), was not an accident of war but rather its main goal. The method of systematical collective dispossession by looting, arson and intentional destruction that was applied in Nahr al-Bared further strengthens these beliefs.

What happens on 15 August will either alleviate or validate the residents’ fears. According to the preliminary reconstruction plan approved by the Lebanese government, on this day the Lebanese army has to allow full access to the old camp to the Palestinians, and have allowed all the rubble to be removed so that the reconstruction process can begin as planned. Any further delay of the reconstruction means that it is increasingly unlikely that all camp inhabitants will return to their communities in the camp, breaking the important social, economic and cultural structures that these refugees brought with them to the camp after their dispossession of their historic homeland in 1947-48.

As for now, there are clear signs pointing at a serious delay of the removal of the rubble in the old camp. An unnamed member of the reconstruction commission told this writer about “a very bad situation” and regards the Lebanese government and its army as the main obstacles to progress on the ground. The army seems to delay a fundamental precondition for site-leveling and rubble removal: permitting the residents to visit the ruins of their homes and collect whatever remains of their belongings. The rubble removal hasn’t started yet and it’s very difficult to imagine that the time between now and mid-August will be enough time to accomplish this task.

Inside one of the many homes in Nahr al-Bared severely damaged by fire.

Besides logistical difficulties, the Lebanese army’s role needs to be questioned. The military still keeps the old camp and even certain areas of the new camp sealed off, while no practical reason for this can be seen. For example, one side of Majles Street, which is in the new camp, as of late April was still fenced off. Since the other side of the street was opened, no de-mining activities carried out by the army could be seen in these houses. Either the Lebanese army is not keen on de-mining these houses quickly or handing them over to its residents. With this in mind, it’s hard to believe that the Lebanese army will stick to the schedule regarding the old camp. The military could easily avoid such speculation if it simply allowed at least journalists and human rights organizations unrestricted access to the old camp (without interference or escorting by the intelligence service).

Many residents of the camp are also worried about the explosions they can hear in the old camp on a daily basis. For example, on 27 April, in the morning and around noon, six massive blasts could be heard. Of course, no explanations are provided by the Lebanese army and nobody else is able to investigate the source of these explosions. Even if mines, booby-traps or other ammunition are being blown up for de-mining purposes, the ruins of civilian houses are affected and their owners have a right to at least be informed.

Meanwhile, residents of the old camp have been issued permits to enter their former homes. However, only a few members of each family are allowed to return to the ruins of their houses. Usually, they are escorted by army personnel and only allowed in for a very short time. As a result of these restrictions, many refugees are unable to remove many possessions or big or heavy items from their homes (if they haven’t already been looted or destroyed). Furthermore, residents are not allowed to visually document the remains of their homes in the old camp.

There are numerous questions that must be answered to allay residents’ fears that the political goal of the camp’s destruction was the slow displacement of Nahr al-Bared’s residents, and therefore a significant reduction of the camp population in Lebanon where the question of the Palestinians in the country is historically contentious. Residents wonder why the old camp is sealed off and movement in opened parts of the new area of the camp is restricted if Fatah al-Islam was declared to be expunged from the camp. Journalists and human rights organizations are still denied unhindered access to all areas of Nahr al-Bared and cameras are banned from the camp. Remaining structures in the camp bear evidence of looting and arson. A year after Nahr al-Bared’s residents fled their camp, there are more questions than answers, and as the power controlling the camp, the Lebanese army is responsible for responding to them.

Ray Smith is an activist with the anarchist film collective a-films, which has short films from and about Nahr al-Bared available for download on its website: http://a-films.blogspot.com.