The Electronic Intifada 12 November 2008

The Israeli authorities absurdly claimed “that a Palestinian gunman wearing fatigues had been shooting a pistol at a watchtower and had been targeted by a member of the Israeli Defense Force [‘IDF’].”

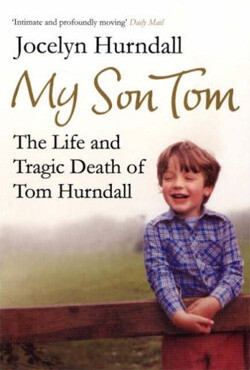

His mother Jocelyn, the author of the harrowing memoir, My Son Tom - The Life and Tragic Death of Tom Hurndall (with Hazel Wood), travels to Israel. At the Soroka Hospital in Beersheva she recognizes her comatose son “despite the bandages surrounding [his] dreadfully swollen head, covering [his] eyes.” She learns that one senior doctor has suggested that his wound was “commensurate with a blow from a baseball bat,” and realizes that the cover-up culture is not unique to the Israeli army.

She travels to Rafah where members of the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) explain how Tom — wearing the orange fluorescent jacket unmistakably identifying a peaceworker — had witnessed children being targeted by an Israeli sniper, had picked up a little boy and brought him to safety, and was on his way back to collect two terrified girls when he was shot. She meets Salem Baroum, the child Tom rescued, who is “completely silent, utterly traumatized.” Later she visits Salem’s home, “a very small house only partly covered by a roof,” where tea is drunk “sitting on chairs with the rain dripping in.”

Eventually, having refused to meet the Hurndalls, the “IDF” issues its report: a tissue of fabrications, “ludicrous, transparent, so unprofessional it was hard to know how to respond.”

At last Tom is flown back to England, where he is brought to the Royal Free Hospital. Here there is a press conference at which Jocelyn’s husband Anthony openly describes the “IDF“ ‘s report as a total fabrication, and describes that army as “unaccountable and out of control.”

In the same week that the Israeli Judge Advocate General orders a military police investigation into Tom’s death, the Israeli ambassador to the United Kingdom sends the Hurndalls an ex gratia cheque for 8,370 Pounds Sterling (about US$13,000) which bounces owing to “insufficient funds.”

On 13 January 2004, Tom dies. The “IDF” arrests a soldier for Tom’s shooting. Taysir Walid Heib, a Bedouin with learning difficulties (“ ‘I have problems with Hebrew’ ”), is charged with aggravated assault and obstruction of justice, and on 27 June 2005 is convicted of manslaughter, obstruction of justice, submitting false testimony, obtaining false testimony and unbecoming behavior.

In April 2006, after the inquest on Tom, a British jury returns a unanimous verdict of unlawful killing and expresses “their dismay at the lack of cooperation from the Israeli authorities during this investigation.”

Spread across two pages at the literal and metaphorical heart of this book is one of the most powerful photographs I have ever seen (taken by Garth Stead). It shows Tom Hurndall, seconds after being shot, being lifted from the ground by two young Palestinians. The latter are clearly crying out in anguish for assistance. Behind them, to the left from the viewer’s perspective, is someone identified only as Nikolai, his hands clutched to his forehead in shock and disbelief. Further behind, to the right, is an unidentified Palestinian onlooker whose expression cannot be deciphered. In the center, Tom is passive, deceptively peaceful, his eyes shut, already somewhere else. Jocelyn Hurndall compares this picture to “Michelangelo’s Pieta with its sense of human vulnerability, of our dependency on one another.”

The comparison is apt, yet problematic. The central figure in the classical Pieta is Jesus, the Palestinian Jewish Arab. The dead redeemer is rendered as a white European male held by his white European mother.

A beady-eyed devil’s advocate might point out that in this photograph the named Palestinians (Amjad and Sahir) earn identification by their association with the injured European would-be redeemer, while the Palestinian in the background is anonymous. Are we here again dealing with the all-too-prevalent denial of agency to the oriental victim? Given the thousands of Palestinian dead since the start of the second Palestinian intifada, is it not over-indulgent to devote almost 300 pages to a single dead European who had only been in Palestine for a few days?

I have no idea whether Jocelyn Hurndall and her co-writer took conscious pains to avoid this pitfall, but, by and large, they succeed admirably and poignantly. From the moment that Jocelyn arrives in Israel, her attention is directed towards the suffering of Palestinians and the intolerable oppression to which they are daily subjected by the Western-backed Israelis. The comparison with South African apartheid, which she had witnessed as a child, imposes itself from the outset.

When she first meets Salem Baroum and his family, she senses without resentment the near cynicism with which she is observed by wary Palestinian male onlookers. The women, on the other hand, recount stories of “days and nights of loss, intimidation, humiliation and destruction.”

When Taysir Heib is convicted, she informs herself about the plight of the Bedouin in Israel and concludes “that Tom was the victim of a victim, that it was the people … who had put Taysir in this position who should be on trial …”

She writes to former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, and currently the Quartet’s Middle East convoy, vainly asking him “to challenge Mr. Bush’s support of this deeply immoral regime …,” and to his wife Cherie Blair who “had recently met some Israeli victims of suicide bombings,” but fails to elicit anything but “cautiously phrased letters” which she contrasts with the emails and letters of support she received “from distressed Jewish people living in [Britain].”

Not content with lamentations and demonstrations, Jocelyn Hurndall and the UK National Union of Teachers have “set up a scheme in Gaza in Tom’s name to give learning support to children with disabilities.” This charity and this book are the testimony of a decent person whose almost unimaginable loss awakens in her the very solidarity with an oppressed people that had cost Tom Hurndall his young life.

Raymond Deane is an Irish composer and activist (www.raymonddeane.com).

Related Links