The Electronic Intifada 13 October 2017

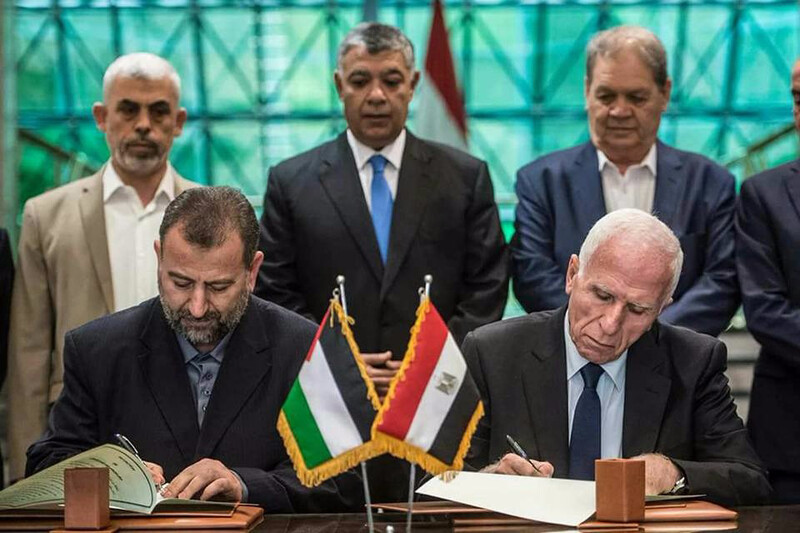

Hamas’ Saleh Arouri (left) and Fatah’s Azzam al-Ahmad sign a national reconciliation pact in Cairo on 12 October.

APA imagesIt was with almost unseemly haste that Fatah and Hamas, the two main Palestinian factions, announced that they had reached a preliminary unity agreement in Cairo on 12 October, after two days of negotiations.

The deal has been greeted with some fanfare. Mahmoud Abbas, head of Fatah and the Palestinian Authority, called it “a declaration of the end to division and a return to national Palestinian unity.”

“We have opened the door to reaching this reconciliation,” said Saleh Arouri, the head of the Hamas delegation in Cairo.

Crowds took to the streets in Gaza to celebrate the announcement, optimistic that the agreement could bring real change for the impoverished coastal strip that could prevent a long-predicted, full-blown humanitarian disaster.

Obstacles and optimism

But real obstacles remain, and any optimism that a breakthrough has been achieved must be guarded.

This is not the first agreement that has been struck in the 10 years since 2007, when Hamas ousted Fatah forces from Gaza. In fact there have been four, all of which eventually dissipated in mutual recriminations: Mecca (2007), Cairo (2011), Doha (2012) and Gaza and Cairo (2014). There were also the Sanaa declaration in 2008 and the Cairo accord in 2012.

Some of the issues that prevented previous disagreements from being resolved have been addressed this time. Pay for some 40,000 civil servants hired after Hamas ousted Fatah forces and the Palestinian Authority paid former civil servants to stay home was one such sticking point. Under the agreement announced yesterday, the PA has agreed to pay half of what their salary would be, equivalent to what they are being paid now, pending vetting of their qualifications.

Some 3,000 Fatah security officers are to join Gaza’s police as a first step for the PA to take control over Gaza. Moreover, the Palestinian presidential guard is to take up responsibility for crossings from Gaza to both Israel and Egypt, the latter at Rafah to be supervised by an EU border agency, EUBAM.

But there has been no resolution as to what to do with Hamas’ military wing, estimated at some 25,000 strong. In the past week, Abbas has called on Hamas to lay down its arms, a demand that is unlikely to be met. That in turn means that Fatah security control over Gaza, at least in the short term, will be mostly cosmetic.

Israel the spoiler

There is also no agreement on any overall political program, an issue that could prove problematic should the most important player in this equation, Israel, dig in its heels.

The Israeli response has not been promising.

“Israel will examine developments on the ground and act accordingly,” the Israeli government stated in response, warning that any reconciliation agreement must include compliance with Quartet conditions, spelled out under the 2003 roadmap plan for peace, which include a recognition of Israel’s “right to exist” and an end to armed resistance.

While Hamas’ new charter paved the way for de facto recognition of Israel, calling the establishment of a Palestinian state on the 1949 armistice lines and the return of refugees a “national consensus,” it “rejects any alternative to the full and complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea.”

Moreover, armed resistance to a military occupation is enshrined under international law and also asserted by Hamas as the “strategic choice for protecting the principles and the rights of the Palestinian people.”

Hamas might well implement a long-term ceasefire – which it effectively has since 2014 – but that is likely the furthest Hamas is prepared to go, and it is not clear whether this will be enough for Israel.

Egyptian interests

Cairo has played a key role and has a number of interests at stake. Cairo wants to enlist Hamas in its efforts to quell a Sinai insurgency that has proven resilient to draconian military measures.

Deploying the army in the Sinai Peninsula is taking valuable resources away from a military that is also engaged in Libya – whose civil war, now in its sixth year, is regarded as a direct national security threat by Cairo. It is proving a drag on an economy whose recent growth has been largely driven by public investment and which has seen its important tourism sector falter as the number of visitors to the country plummeted.

Hamas has proven a willing partner, even as it rejects Egyptian accusations that it has actively abetted Sinai militants. Security forces in Gaza have begun clearing a buffer zone in Rafah, along Gaza’s boundary with Egypt, to prevent arms and people smuggling. Hamas has also arrested Salafi activists in Gaza and become a target itself for militants, most recently in a suicide bombing in August in the boundary area with Egypt that killed one of its officers.

But Sinai is not Cairo’s only priority. Egypt is trying to improve its regional standing, undermined by the turmoil and bloodshed of the 2011 revolution and 2013 military coup. A successful unity agreement will be a significant diplomatic victory for Cairo. That, in turn, may convince Washington – where the US Congress is withholding some $95 million in aid and delaying a further $195 million over Egypt’s human rights record, including abuse accusations in Sinai – that Cairo remains a crucial player in the region, and therefore an important partner for US interests, a status it enjoyed for decades until the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak.

Easing the blockade

Fundamental to the success of any agreement will be to what extent Egypt is willing to ease the blockade on Gaza. Without an opening for goods and people there is no reason for Hamas to compromise and no benefit for Gaza.

Only then can the $5.4 billion pledged by governments to rebuild the battered coastal strip after Israel’s 2014 assault begin to make a difference.

Cairo seems serious. Not only is it the only way to ensure Hamas cooperates on Sinai, Cairo’s efforts to bring Fatah and Hamas together were partly an attempt to secure PA cover for such an opening. An earlier agreement with Muhammad Dahlan, the erstwhile Gaza security chief, sworn enemy of Hamas and longstanding Abbas rival, would not have provided this cover, but would likely have functioned as leverage over Fatah in negotiations. The last thing Abbas would have wanted was for Dahlan to re-enter Palestinian politics through Gaza and Hamas, Egypt and the UAE, which promised to bankroll that deal.

Israel might well balk at this. Its blockade has prevented reconstruction of the hundreds of thousands of homes and other buildings its military damaged or destroyed over three deadly assaults, and rendered essential utilities at near-collapse, leaving Gaza at the risk of a humanitarian disaster that the UN has warned could leave the strip uninhabitable in three years.

Egypt’s ruler Abdulfattah al-Sisi has proven willing to go his own way on several issues in pursuit of what he sees as his country’s interests.

He broke with Riyadh over Syria in 2015, even though Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries were important financial backers in the years after al-Sisi ousted the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood president Muhammad Morsi in 2013. And he has reached out to Moscow, as relations with the US soured under Barack Obama.

”You looking at me?”

Nevertheless, Cairo will only go so far to defy Israel and much will depend on what happens on the ground. Hamas is likely to go the extra mile to ensure that the agreement sticks. It has been weakened by the loss of its most important sponsor when Gulf countries moved to isolate Qatar, and has seen Gaza suffer not only three devastating Israeli military assaults, but sanctions imposed by the Palestinian Authority in Ramallah.

Abbas, meanwhile, has little to show for his presidency. Stubbornly committed to a peace process of which he was a primary architect but which has brought little but new Israeli settlements in occupied territory, the octogenarian leader is likely on his last furlong. A successful unity agreement might just set him up for one last stab at negotiations. It also ensures that Dahlan is kept out of the equation a little while longer.

But while the weakness of both sides provides some common ground, mutual confidence remains low. And where Hamas is isolated, Abbas’s PA is largely dependant on funding from the US and EU, giving both undue leverage.

Not only do both consider Hamas a terrorist organization, the current US administration, for all its talk of brokering an ultimate deal, has said or done nothing so far that has veered significantly or even slightly from Washington’s pro-Israel orthodoxy.

And even if all those potential stumbling blocks can be cleared, any progress toward lasting reconciliation can at any moment be canceled by Israel.

A warning this week by a top Israeli general that escalation would likely result from “provocative actions” by Hamas fighters aiming laser pointers at Israeli soldiers – surely the military equivalent of a bar room drunk’s “you looking at me?” taunt – shows just how easily that could happen.

Omar Karmi is a former Jerusalem and Washington, DC, correspondent for The National newspaper.