The Electronic Intifada 29 July 2003

Film poster for Gaza Strip

“Almost everyone in the Gaza Strip had a story and, if you were patient, they would probably tell it to you.” — James Longley

James Longley’s Gaza Strip is a 74-minute documentary filmed between January and April 2001, a period that stretches from four months after the beginning of the Second Palestinian Intifada — immediately preceding the election of Ariel Sharon as Israel’s prime minister — up to the end of Sharon’s third month in office.

“I made this film,” Longley notes in the director’s commentary that accompanies the very highly recommended DVD version, “to satisfy my own curiosity about what was happening in the Gaza Strip since I found that it was very difficult to find information in the mainstream media and get a detailed look at what was going on, what people there were like, what they were thinking about.”

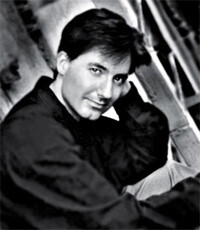

Longley studied film at the University of Rochester and Wesleyan University in the United States, and the Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. He was awarded the Student Academy Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his short 1994 documentary co-directed with Robin Hessman, “Portrait of Boy with Dog,” about a boy in a Moscow orphanage. Last year, Longley returned his award in protest at the Academy’s clear prejudice against the Palestinian film Divine Intervention.

Gaza Strip centers around another boy, Mohammed Hejazi, a 13-year-old Palestinian who lives in Sejjaia, a neighbourhood in Gaza City, and works as a paper boy. Longley first met Hejazi at the Karni Crossing, an Israeli-controlled border between the northern part of Gaza and Israel proper, the site of regular stone-throwing clashes between Palestinian children and the Israeli military.

Typically, 50-60 kids go once a week to throw stones in what is primarily a symbolic gesture due to a murderous geography that places the Israeli checkpoint temptingly out of stone-throwing reach but well within rifle range of the Israeli soldiers stationed there. The resulting casualties among children, confirmed by multiple human rights organisations, have been high, despite no credible threat to the soldiers. Longley had read of these young kids in a New York Times article and, after arriving in Gaza, sought the kids out as documentary subjects. “They’re not really doing anything effective against the occupation and they know this,” says Longley, “but they are resisting it, in their own way.”

Mohammed Hejazi (James Longley)

The likeable and cheeky Hejazi is not representative of other Palestinian kids his age in that he is a high school dropout whereas Palestinian families typically place a high priority on education. Indeed, Mohammed’s elder brother ranked second academically in his age range in all of Gaza and all his other school age siblings were doing very well. But his disassociative outlook on life and the survival humor that he employs to overcome his desperate situation speaks of every one of Gaza’s children. All children dream and imagine. In war, children dream of liberating their land and imagine lives outside the oppressive confines of their life. Mohammed is such a dreamer, incredibly articulate for his age. Gaza Strip has no director’s narration in the cinema verite tradition of realism and presents commentary from Mohammed and other Palestinians as is, with easy-to-read subtitles for non-Arabic speakers.

James Longley, director and producer of Gaza Strip.

Against a background of donkey carts and bogged-down cars struggling along Gaza’s beach to circumvent Israeli checkpoints in the ongoing struggle to maintain a normal life — no matter what — Longley presents vox pop commentaries from a situationally ‘democratic’ trudging line of Palestinians making their way along the shore: men and women, young and old, the obviously poor and those more well-to-do. Scenes like this are like a punch in the stomach, undeniably bringing home the central fact of life under occupation — it is not only Palestinian militants that the on-the-ground mechanisms of occupation target, but every Palestinian.

The common sense apparent in the complaints of all gives you a clue of the strong grounding that conflict brings to people that must live in it, as well as a desperately-needed antidote to the impression left by images of Palestinian violence and demonstrations that disproportionately fill our television screens.

This same space is given to those present in the aftermath of the death of a child who picked up a disguised explosive device, left behind by an Israeli tank. Similarly, we are forced to confront the unquestionable normality of fathers, mothers, and their children in the disturbing medical aftermath of an Israeli deployment of nerve gas against Palestinian civilians. This last point underlines why this documentary meets such a critical need.

“It was strange to me,” says Longley, “that this particular incident never made it out into the mainstream media, especially in the US.” On 12 February 2001, following an Israeli attack involving a gas with characteristics clearly different from and much more severe than the ubiquitous teargas, 50 people were brought with severe reactions to Amal and Nasser hospitals in Khan Younis. The following week saw this figure rise to a total of 200 people, still suffering ill effects from the gas, including violent and painful convulsions.

A Gazan girl from the film. (James Longley)

Evenly balanced between scenes of individual tragedy and vistas of mass suffering, Gaza Strip is a compelling portrait of human life during wartime, a powerful tool for explaining in simple terms what is wrong with the Israeli or indeed any long term foreign military occupation, and a call for us to pay attention to situations our governments underwrite that generate deserved hostility from our other neighbours on this planet.

The documentary works to dispel a number of pervasive myths about the conflict that have rendered Palestinians into two dimensions in the world’s media: that Palestinian parents permit their children to participate in stone throwing or even indeed know of their participation; that Palestinians as a whole stand behind the leadership of Yasser Arafat; that Israel’s use of military force is either proportional or even aimed at all at actual Palestinian combatants; and that the Palestinian people do not want peace with Israelis. All these notions are exposed as patent nonsense when you accompany Longley on his journey through Gaza, and meet Joe and Jane Palestinian for yourself.

After watching Gaza Strip, a documentary made by a citizen of the country that bears primary responsibility for the continuation of the conflict, what condemns us most is that they don’t hate us. The lack of rancor evident in the Palestinians seen through Longley’s lens is a powerful word of peace spoken by a people whose oppressors have invested much to falsely represent as violent and uncompromising.

What Palestinians “hate” — a term clearly inappropriate given the wide age and social ranges of the interviewees in Gaza Strip and the fact that most offer calm, concise and detached reportage of the horrible events they are forced to live through — is what we all should hate: violence visited on the poor and helpless in a manmade tragedy that the international community and the United States in particular could do much to resolve.

The official film website for Gaza Strip at www.littleredbutton.com. Click to visit.

There is much more that could be said about this simple but powerful documentary but — in brief — this testimony is sorely needed and deserves as wide an audience as possible. Do your part for this excellent independent film. Go buy it now and give a copy to everyone you know.

Cover of the video/DVD.

Nigel Parry is one of the founders of The Electronic Intifada.