East Jerusalem 12 August 2009

A poster hanging in the Hanoun family home in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, March 2009. (Anne Paq/ActiveStills)

At 5:15am on Sunday, 2 August, I woke up to the sound of the Hanoun family’s front room windows being smashed in. I had just laid down to rest only 20 minutes earlier.

The Hanoun family is one of 27 families in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem facing eviction from their homes as part of a plan to implant a new Jewish settlement in the area. They are refugees from 1948, after being displaced from their home in Haifa during the Nakba, or catastrophe. The family includes 18 members, six of whom are children. They have lived in Sheikh Jarrah since 1956 when the Jordanian government and the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) gave them their houses as part of a project to house Palestinians forced to flee their homes.

We knew that the threat of eviction was imminent ever since the first order of this year was served on 19 February. The family had already been kicked out of their home once, in 2002, but it was still hard to imagine that the day would ever come.

By the time I’d got to my feet, scores of soldiers were rushing into the house and had surrounded me. Due to my disability — I have cerebral palsy — I cannot walk at a fast pace, which they used as an excuse to increase their level of aggression, kicking me as I fell to the ground and pushing me out the front door. As I tumbled down the stairs outside, I pointed at my wheelchair:

“That’s my wheelchair,” I said. “I need it because I can’t walk.”

“No! No!” the armed Israeli forces replied, continuing to shove me away.

Just outside the house, the police gathered everyone at a nearby wall. Within a matter of seconds they had confiscated everyone’s camera and mobile phone, meaning that no footage could be taken and no media could be called. Media would have been able to reach the house anyway as a team of 500 police officers had closed off the entire area. The few journalists that did finally manage to enter the area by climbing through neighboring gardens were manhandled and harassed by Israeli forces.

The police promptly proceeded to arrest all of the international activists present who had been staying with the families in Sheikh Jarrah to show their support. As they forced the internationals away from the house, a police barrier was hastily set up, imprisoning them on the road facing the house. I was the only international left with the family. All around me I could see tears falling from eyes, and faces falling into hands. Children distraught. A family broken.

“For the second time, I have been kicked out of my home,” sobbed Jana Hanoun, 16. “How can I ever forget?”

As one of the grandmothers stood cursing the gathered soldiers for their crimes, one of them took offense and attempted to strike her in the face. Her son tore down part of the barrier, launching himself at the soldiers until he was brutally beaten and crushed to the ground. Other Palestinians were also injured as they desperately tried to prevent his arrest.

It was only a couple of hours before a van of Jewish settlers drove up and began moving in to the Hanoun family’s house. I watched as soldiers ushered the settlers through to the house they had just stolen. A distraught Jana had to be held back from scaling the fence, for fear that she would be the next to be beaten.

This is occupation. This is apartheid.

By 5pm, the police finally took down the fence and reopened the roads outside the house. We all immediately crossed the road, put our banners back up and sat on the steps outside the Hanoun home. Soldiers forced us across the road once more and erected a new fence.

In the evening, individuals from across the country gathered outside the house to protest, and we chanted as loud as our voices would allow. The Israeli police responded to the peaceful protest by brutally beating participants — punching people in the head and throwing a woman with a baby in her arms to the ground. Thirteen more arrests were made.

I had been staying with the Hanoun family for weeks before the eviction took place, and vowed to continue to do so. I felt a portion of their pain that morning — I was also kicked and dragged from the house in which I was living. My belongings were also left behind as I sat shoeless on the street.

We slept the night on the pavement opposite the home.

The next day I was struck by the beaming smile still on the face of Sherri-Ann, a 20-year-old member of the Hanoun family and psychology student. She had an exam to take only a few days later.

“They want Arabs to be stupid, so that when we shout, no one will hear us,” she told me. “But I will continue to study and achieve good marks. I will never give up.” I watched with admiration as Sherri-Ann sat under the olive tree opposite her home, where she had lived her whole life, and told the story of the eviction to interested visitors.

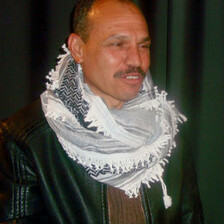

It’s difficult to keep hope as we spend the days sitting on the pavement in the blazing heat, watching as the settlers walk in and out of the Hanoun family’s front door, laughing and gloating with the Israeli police on 24-hour duty. But the family is the strongest I have ever met, and Maher Hanoun, the 51-year-old head of the family, remains defiant.

“We have been made refugees again,” he told reporters. “This is a slow genocide they are conducting against the Palestinians of East Jerusalem.”

He added that “For the last 37 years we were fighting to keep our homes, and now begins the fight to get them back.”

Jody McIntyre is a journalist from the UK. He writes a blog for Ctrl.Alt.Shift, entitled “Life on Wheels,” which can be found at www.ctrlaltshift.co.uk. He can be reached at jody.mcintyre A T gmail D O T com.