The Electronic Intifada 28 April 2008

In 1963, Arjan’s father Walid El Fassed arrived in the Netherlands along with 65 other Palestinians from Nablus as a migrant worker. He eventually fell in love with and married the girl next door, Maretje Vermeer. During Israel’s initial census after seizing the West Bank in the June 1967 War, Walid was in the Netherlands and thus he became “displaced,” like tens of thousands of other Palestinians who were abroad at that time.

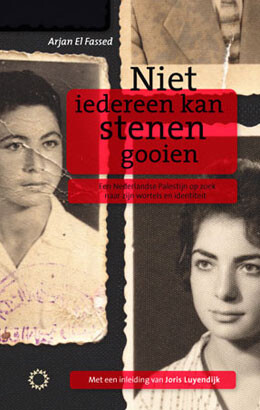

Walid and Maretje’s son Arjan was born 35 years ago in Vlaardingen, a small provincial town in the Netherlands. Inter-religious marriages were not common at the time, and almost unthinkable when one partner was Muslim, making El Fassed’s family a unique one.

In one of many poignant moments in the book, El Fassed tells the story of a visit with his father to Nablus. His father shows him their family’s house, built in 1918 by El Fassed’s great-grandfather Salim El-Fassed and his two brothers. The original tile floor that was produced in their family’s factory is still there. Arjan El Fassed and his father Walid were in Palestine to attend the marriage of their cousin Nidal, the son of his father’s sister Enaya and uncle Bassam Shaka’a, who was the mayor of Nablus in the 1970s. The description of the journey is mixed with childhood memories, supported by historical facts and details from media reports and other publications.

In another passage, El Fassed recalls hearing about a car bomb attack on his uncle Bassam on the radio while sitting at the kitchen table as a six year old boy. His mother turns up the volume and calls the Dutch press agency ANP for more information. That evening the attack appears on national television, and El Fassed hears his uncle making a statement from the hospital: “They ripped off both my legs, but this only means that I am closer to my land. I have my heart, my intellect and a just aim to fight for, I don’t need my legs.” The car bomb attacks on three Palestinian mayors were perpetrated by a Zionist terrorist organization. The attempt to silence the mayors failed and as a Time magazine poll affirmed, they became national heroes.

The book’s second section examines the period from September 1996 until October 1998. During this period El Fassed lived in Nablus and worked for the Center for Palestine Research and Studies and in his book he describes his neighborhood and how he got to know his family and made friends. He also comments on the practices of the Palestinian Authority (PA), denouncing its corruption, the torture of Palestinians in PA prisons and the (self-)censorship in the media. He also recounts how he engaged politically, and after returning from a demonstration near an Israeli checkpoint his uncle Bassam bluntly explained, “Arjan, some Palestinians are good in throwing stones, others in writing or political work, because they have the talent to do so. Arjan, you don’t have the talent to throw stones.”

In the final section, Arjan discusses his work for the now-defunct Palestinian human rights organization LAW from May 2001 until October 2002 where he set up a communications and lobby department. Within months he is confronted with the oppression and violence of Israel’s response to the second intifada. There are tanks in the streets of Palestinian cities, rocket attacks, extrajudicial killings, curfews, house arrests, deportation of Palestinians, and Palestinian homes are taken by the Israeli army as a military base or detention center. Many civilians were killed and the construction of wall on Palestinian land starts. Meanwhile, journalists and diplomats phone El Fassed day and night at LAW for the latest information. As an eyewitness and a participant, El Fassed was appalled by the silence of the world to Israel’s blatant violations of international law. He states that “If there is a place where human rights are not universal, it is here. It looks like apartheid, it smells like apartheid, it feels like apartheid. But the world does not want to see it.”

Although the book’s subtitle is “A Dutch Palestinian in search of his roots and identity,” its contents demonstrate that El Fassed identifies himself primarily as a Palestinian. This is a powerful statement in the current Dutch context, where society and politicians pressure immigrants and their children to assimilate into Dutch society and “become Dutch.” Yet, Arjan proudly wears a keffiyeh, the traditional Palestinian scarf, in his book, but no longer to cover his face.

Adri Nieuwhof is an independent consultant and human rights advocate.

Related Links