The Electronic Intifada 23 July 2013

At their worst, some of these accounts are ill-informed expropriations of Palestinian experience and suffering.

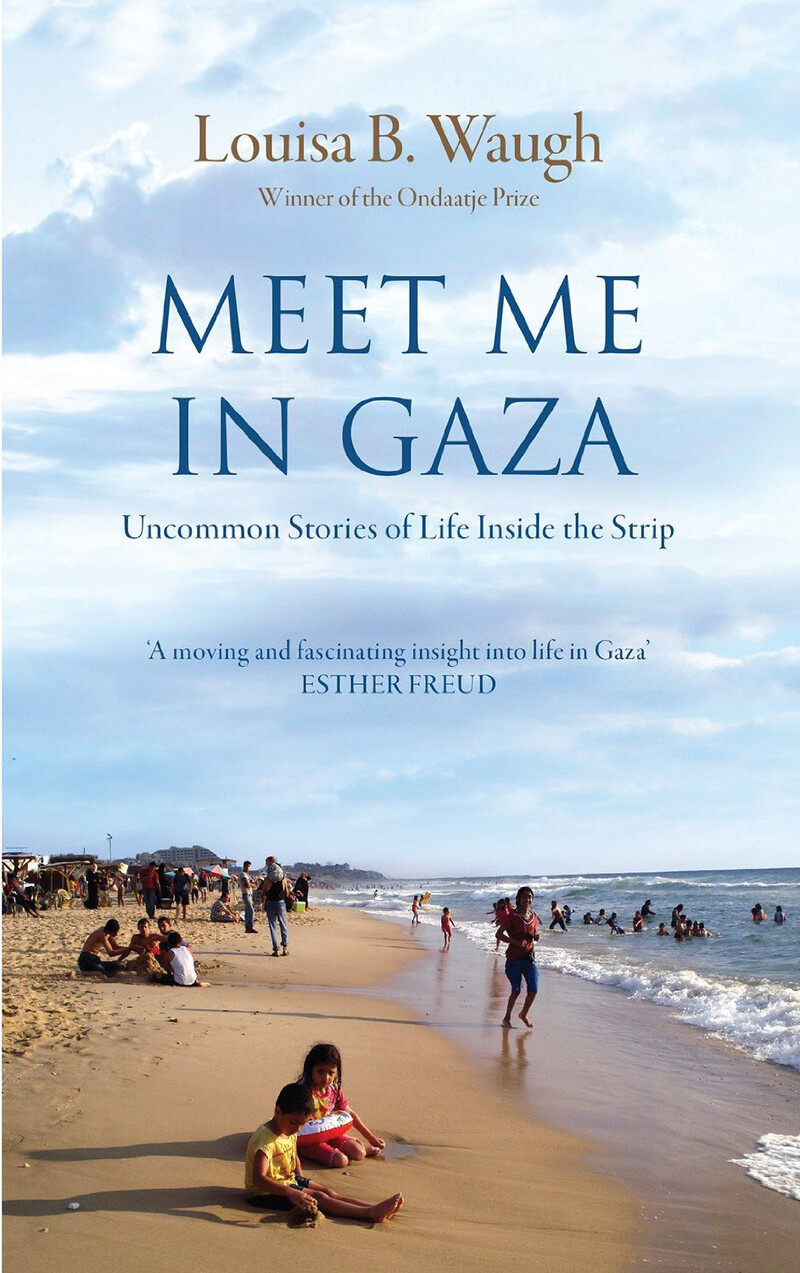

Meet Me in Gaza, Louisa Waugh’s excellent narrative of her years living in Gaza between 2007 and 2010, is at the opposite end of the spectrum.

Waugh is not an “activist.” She belongs rather to the school of travel writers who spend long, intense periods in countries rarely visited by Westerners, documenting life with an observant eye and a neat turn of phrase.

Are such projects Orientalist, as colonialist as the early anthropologists who “explained” the cultures of “others”? Perhaps. And perhaps it should be unnecessary for Western activists to “get to know” the peoples they offer their solidarity to — maybe a political analysis of the situation should be enough?

But in reality, there are multitudinous injustices clamoring for attention; perhaps many of us therefore end up engaging with the causes that resonate for us as individuals. And Waugh’s book offers the kind of warmth and intimacy that can inspire that resonance.

Salt and spice

It is also distinguished by a lack of ego; although Waugh’s time in Gaza may frame the narrative, the real center of the book are the people of Gaza and — delivered in small digestible chunks — their long, vivid, salt-and-spice history.

For people who know nothing of Gaza but lazy media stereotypes, this book is a perfect introduction. And for those who think they know all the facts and figures, there will be some small surprise.

There is the “religious accountant … who performs acrobatics on the beach.” Or the tale of shopping for risqué lingerie in Gaza City’s Souq al-Bastat (a market). Being female also allows Waugh to offer glimpses into women’s spaces — dancing in bedrooms or steaming in Gaza City’s famous Mamluk hammam (baths).

This isn’t to say that Waugh’s account is a whitewash of the situation. Working with a Palestinian human rights organization, she recounts some of the horrific testimonies she heard from survivors of Operation Cast Lead (Israel’s all-out attack on Gaza in late 2008 and early 2009).

She includes the tale of a 16-year-old boy who saw his mother beheaded in the family kitchen by an Israeli tank shell which also killed his four young siblings. He was just feet away. As the human rights workers interview him, he “sits in the armchair, staring, drowning, oblivious that we are even here.”

Aside from the headline news stories, Waugh also tells the tales of some of the most marginalized in this besieged society, especially the “forgotten” Bedouin living at both ends of the Strip.

At the northern end of Gaza, this means a family headed by tough matriarch Manah; she and her children live under constant harassment from Israeli soldiers until finally their house is demolished in the final hours of Cast Lead. At the southern end, we meet a family who have to leave their home several times a week, when Israel bombs the tunnels in Rafah, which Palestinians in Gaza use to bring in goods from Egypt.

Waugh is also not afraid to show the complexities she encountered in Gazan society. She is open about meeting Palestinians who were increasingly frustrated and fearful of the Hamas regime.

Willing to criticize

Some of the Bedouin in Rafah refer to the local Hamas police as “how-how” — a pejorative reference to dogs — while even a deeply religious female friend comments that “the problem is that we don’t have much fun now … when Hamas stopped us women from smoking shisha [water pipe], then my friends decided to stay at home.”

Through Waugh’s eyes we also witness class differences; her dress gets sneered at by two rich matrons from the al-Rimal area, while families fleeing their farmlands close to the boundary separating Gaza and present-day Israel endure grinding poverty.

At the same time, the book debunks some of the myths about Gaza. Even during Ramadan, Waugh is able to attend a Christian engagement party at a beachfront. Bottles of alcohol are kept under the tables out of respect for the Muslim waiters, but when she enquires about the usual stereotype of religious oppression one of the men at the party “twinkles” and asks, “do we look scared?”

One of the important points about this book is Waugh’s willingness to criticize.

This applies to easy targets — such as Bruno, the “asshole” cameraman who claims that “my work is not restricted to war zones … it is more complicated than that … I do tension zones.” But it also goes for activists who try to claim Palestine suffering for themselves and even to Waugh herself.

“Thick as sauce”

Waugh admits to being “black and white” about the Palestinian militants firing rockets into Israel. Although she doesn’t deny their right to such resistance, she feels that the missiles attract retaliation which lead to civilian casualties.

But after discussing the range of opinions among her Palestinian friends, Waugh concludes with one who gently asks her, “Louisa … do you really believe that if the Gazan fighters stop firing rockets, then so will Israel?”

In the end, of course, it is not just the anecdotes that Waugh recounts, or her undoubted skill in selecting them, which make this book such a terrific read. It is also her wonderful way with words, even on the grimmest of subjects. Hamas and Fatah “goad each other like punch-drunk boxers as the roaring crowd flinches,” while the body of 13-year-old Abdul, killed by an Israeli missile, “lies crumpled in the scoop in the ground, his belly imploded, like a small dead bird.”

Less appallingly, on a night of power cuts in Gaza City, “the blackness is thick as sauce.” And she expresses surprise at the delicacy with which men “who looked like Glasgow pimps” handle their pet songbirds.

The beautiful normality of people shines from each page — ordinary, quirky people forced to live in the most brutal of situations, coping one day after another. Waugh’s book is a worthy tribute to them.

Sarah Irving is a freelance writer. She worked with the International Solidarity Movement in the occupied West Bank in 2001-02 and with Olive Co-op, promoting fair trade Palestinian products and solidarity visits, in 2004-06. She is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine, and co-author, with Sharyn Lock, of Gaza: Beneath the Bombs.

Comments

In my opinion, it would be

Permalink Kamran Ghasri replied on

In my opinion, it would be much better if the link to the book does not take you to Amazon. I don't need to remind anybody how bad and evil this corporation is. There are alternative online booksellers, but your local book store should always be the first choice.

kalaam saliim

Permalink Bill Kelsey replied on

kalaam saliim