The Electronic Intifada 19 January 2017

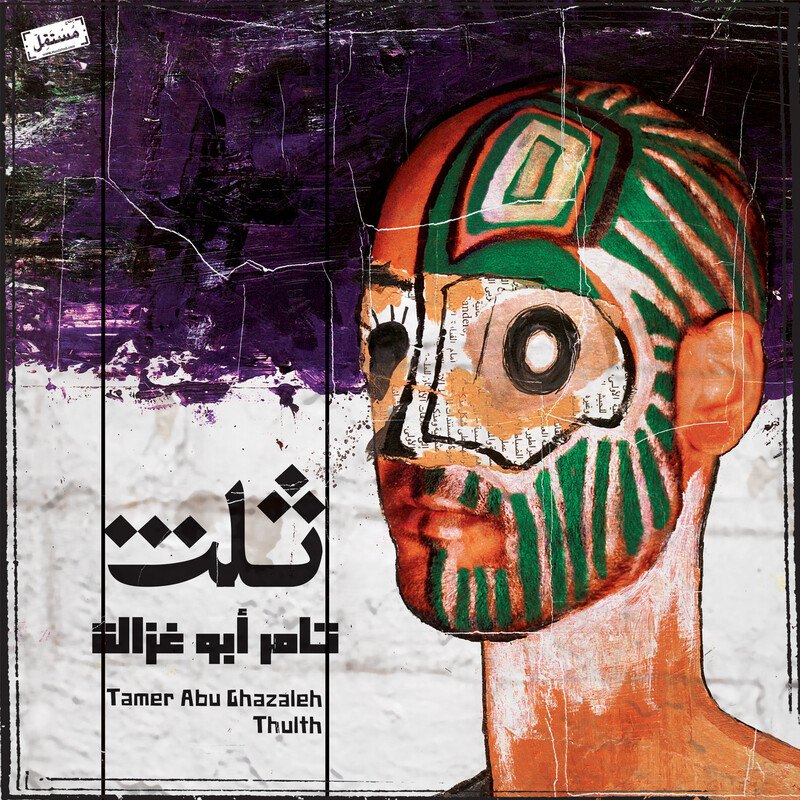

Thulth, Tamer Abu Ghazaleh, Mostakell Records (2016)

The austere name Thulth (Third) gives few clues of what to expect of Tamer Abu Ghazaleh’s third album.

Certainly anyone approaching the collection anticipating simplicity would be shocked, bewildered and exhilarated as they are drawn into this journey through the beauty, anger and ultimate powerlessness of the human condition.

Born in Cairo to Palestinian parents, Abu Ghazaleh is a prodigiously talented musician who released his first album at the age of 15 and has, in the 15 years since, helped to found a record label, booking agency, music magazine, licensing agency and public relations company.

Performing since the age of two, he studied at the Palestinian National Conservatory of Music in Ramallah and has collaborated with and produced albums for many Palestinian, Egyptian and other Arab-world artists.

Abu Ghazaleh’s musical and vocal style is varied and inventive, yielding an album which ranges from the dreamy and delicate to wild, crashing movements, cinematic in their scope and grandeur.

This is music as demanding as a theatrical experience, at times almost dizzying or claustrophobic in its intensity, but drawing the listener in as it dips and climbs between contemplation and whirling, roaring frenzies.

The song “El Ghareeb” (The Stranger), for instance, peaks in clamorous, discordant crescendos; as with much of the album, there is little that is easy to listen to, but it is all thought-provoking.

Although many of the tracks have a sense of spontaneity and vigor, they are underpinned by precise arrangements which enhance the feeling of drama and action but prevent the work from descending into chaos. Abu Ghazaleh isn’t simply displaying raw talent, but skill and sensibility, as well.

Eminent poets, rebellious politics

This sense of a sharp intelligence underlying emotional passion makes itself felt in other ways. In several songs, for instance, Abu Ghazaleh’s voice seems both an homage to and a parody of the flourishes and ornamentation of classic mid-20th-century Arab singers such as Umm Kalthoum or Farid al-Atrash.

In “Takhabot” (Clamor), meanwhile, Western music of a similar era makes its presence felt, with playful excerpts from the theme to the 1963 film The Pink Panther by American composer and bandleader Henry Mancini.

The wide-ranging cultural influences also make themselves felt in the origins of many of the lyrics to Abu Ghazaleh’s compositions.

Like Aynama-Rtama, the 2015 album by Middle Eastern supergroup Alif in which Abu Ghazaleh collaborated, the words in Thulth are drawn from poems by eminent figures of Arabic poetry.

Alif’s album includes songs based on poetry by Palestinian Mahmoud Darwish and Iraqi Sargon Boulos, both major poets of the 20th century.

Thulth, meanwhile, draws on a wide range of sources. They include a pre-Islamic classic of Arabic verse by the semi-mythical Qays Ibn al-Mulawwah, the poet who recorded his love for the beautiful Leyla with a passion that brought him the name Majnun, the Mad One.

Among other inspirations appears a poem by Tamim al-Barghouti, the Palestinian writer and academic who delighted audiences across the Arabic-speaking world with his performance of “Fil Quds” (In Jerusalem) on the Prince of Poets TV competition show.

Al-Barghouti and his poetry have been associated with the rebellious politics and Arab uprisings of recent years, critiquing long-established dictatorships in Egypt, Tunisia and other parts of the Arab world and calling for democratic reforms and human rights – for Palestine and elsewhere.

In “Namla” (Ant), al-Barghouti’s words seem to propose the agonized confusion of an insect floundering in soap lather as a metaphor for social chaos and the challenges facing those striving for personal, cultural and political freedoms.

Much to offer

Ramez Farag, an Alexandrian poet whose words are the lyrics for two of Abu Ghazaleh’s songs, has also been a voice of the movement in Egypt. “Alameh” (Sign), for instance, speaks of the Palestinian desire for home and a decent life – a desire more common now to many others across the war-torn region.

And in other songs, Abu Ghazaleh’s own lyrics express the rage, grief and frustration of younger generations across the Middle East who have seen their hopes for revolution dashed.

In “El Balla’at” (Manholes), the closing track of the album, these emotions reach a crescendo as the bug (reprising the Kafkaesque overtones of the earlier al-Barghouti lyrics) is crushed, left to a filthy, wet death in a drain. It is not an optimistic closing to an album born in and reflecting upon the contemporary Arab world.

The lyrical complexity – from the picturesque imagery of the opening track “Fajrolbeed” (Desert Dawn) to the rising political anger which culminates in “El Balla’at” – means that non-Arabic speakers will face challenges in appreciating the full spectrum of meaning behind Abu Ghazaleh’s album.

Certainly a look at the lyrics – including those for some songs freely available on the Soundcloud stream for Abu Ghazaleh’s Mostakell music label – will help global audiences experience more of the ideas and thoughts behind his work.

But even without a full grasp of the words, Abu Ghazaleh’s third album, like his previous individual works and group projects, has an aesthetic energy and brilliance which goes beyond the meaning of the lyrics, and has much to offer even the casual listener.

Sarah Irving is author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor of A Bird is not a Stone.

Comments

Woow

Permalink Luana replied on

This one is amazing I really like this one. can I listen to Tamer Abu third album on setbeat app(http://setbeat.net)?