The Electronic Intifada 30 October 2008

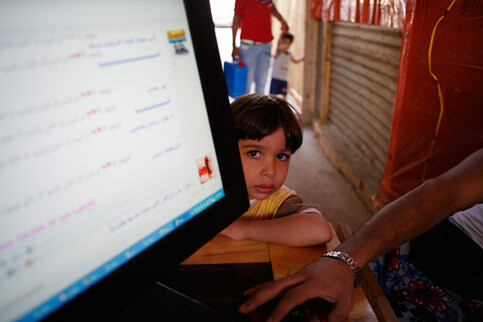

Palestinian youth in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in Lebanon spend much of their time at Internet cafes chatting with other Palestinians in Palestine and around the world. (Matthew Cassel)

Ask Saif Abukeshek when he became an online activist, and he’ll give you the same answer as many of his Palestinian peers: after the second intifada erupted, in 2000. That explosion of violence in the occupied territories brought about a tough lockdown on Palestinian mobility by Israeli forces and produced the right conditions for a home-grown, grass-roots activism — frustrated youth trapped inside all day with nothing but the TV and the internet to turn to. “It’s a way to achieve effective non-violent resistance,” says Abukeshek, 27, who is from the West Bank city of Nablus but now lives in Madrid where he helps run Pal-youth.org, an online Internet portal connecting Palestinians around the world.

“The biggest hallmark of the younger generation of Palestinians is their inability to move,” says Dr. Karma Nabulsi, a professor of politics and international relations at Oxford University. But the internet knows no borders and neither, says Abukeshek, does the Palestinian cause. Their reduced mobility, combined with increasing internet access, has led the stone-throwing Palestinian children who, for many, became the lasting image of the first intifada in the late 1980s and early 90s, to bring their resistance online during the second. Sociologists call the movement “e-Palestine”: a feeling of nationhood cultivated online by young members of the fractured diaspora, some living in the confines of the occupied territories; others born and raised in exile and connected to Palestine at a remove of several generations. With the Internet domain suffix “.ps,” this young online community has acquired a kind of international recognition that the physical Palestine can only aspire to.

The hardware required to create “e-Palestine” — computers and modems — is certainly in place in both the occupied territories and throughout the diaspora. Today, a ubiquitous feature in the Palestinian camps across the Middle East is the internet cafe — a loud, smoky space crammed with young Palestinians clustered around a handful of computers, faces lit up by the glowing screens, communicating with other Palestinians they have never — and may never — meet.

Online, Palestinian youths don’t have to navigate the political allegiances — primarily to the warring Fatah and Hamas factions — that crisscross the camps and which have torn the West bank and Gaza apart. These tensions don’t dominate “e-Palestine”: experts estimate that up to 60 percent of young Palestinians are not members of any faction — an enormous break from the extremely high rate of party affiliation of previous generations.

Gender relations are also different online, where young men and women flirt openly across the borders and obstacles that have been placed between them. In one internet cafe in the Beddawi refugee camp in northern Lebanon, one teenager leaned over to show me his girlfriend in Gaza, smiling out at him through a grainy, time-delayed webcam shot. Men and women can communicate with an ease and frankness that Palestinian social mores are less permissive of. In his IM window, the young Palestinian book-ended a flirtatious message to his Gazan girlfriend with a line of heart and angel icons. He flashed a quick grin and hit enter.

One popular program, PalTalk, has chat rooms and forums with names like “Palestine News” and “Jerusalem 4ever,” and “Palestine4ever,” all popular venues for Palestinian youth around the world to discuss ideas, news and share photos and videos from their own corner of the globe. “In the beginning it was just casual chatting and discussion, the themes were arts and culture and sport,” says Abukeshek of the chat rooms he frequented before getting involved with Pal-youth.org. “But then I noticed more and more political chat rooms appearing over time — the Palestinians in Palestine had to express what was happening inside, and the Palestinians outside of Palestine had a need to learn about it.”

The hallmarks of Palestinian cultural resistance — poetry, graffiti, commemorative objects — that can be found on the walls of camps and in Palestinian homes now adorn the cyber-surfaces of “e-Palestine.” IM windows are decorated with digital renderings of the Key, a symbol of exile that hangs on the walls of living rooms. The figure of Handala, cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s iconic homage to the Palestinian refugee, adorns many social networking profiles. This year, to mark 60 years of exile, what the Palestinians call the Nakba — or “disaster” in Arabic — entire days in chatrooms and forums were dedicated to discussing the Nakba and what it means today. “Traditionally for Palestinians, the Nakba has been about looking back in sorrow,” says Nabulsi. “But what I am seeing among younger people now is that they are using Nakba commemoration to look forward.” For Abukeshek, it’s about finding a jumping off point for action. “It’s an event we can mobilize around,” he says.

Abukeshek and Pal-youth.org’s next step is to formalize an online political mobilization plan for young Palestinians on the ground throughout the world. To this end, the organization is bringing together 150 Palestinians from 28 countries for a summit in Madrid in early November. “Everyone thought that bottom-up mobilization was dead [in America].” Says Dr. Nabulsi. “But they got a shock with Obama, and I see it also with the young Palestinians.” And although he says he disagrees with Barack Obama’s politics, particularly on maintaining an undivided Jerusalem, Abukeshek says he is encouraged by the influence the presidential candidate’s online campaign has had. “The way he uses the internet to reach groups that have not been involved in the political process before, and with such success is an inspiration to us.”

Don Duncan is a freelance print and radio reporter and videographer. Originally from Ireland, he has lived and worked in several countries including Afghanistan, France, Hong Kong, Lebanon, Spain, the United States. He currently lives in Hong Kong where he works for TIME magazine. This article originally appeared on TIME.com and is republished with the author’s permission.