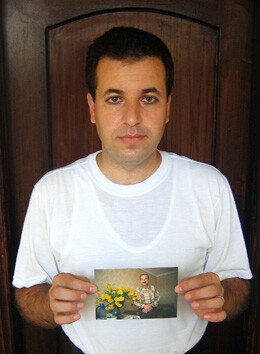

Raed, a doctor from Gaza living in Ukraine, was stranded at the Gaza-Egypt border when his father was dying in Gaza. (Eva Bartlett)

It was Wednesday, 20 August in Sinai’s al-Arish, a town about 50 kilometers west of the Gaza-Egypt border. Two days earlier, the approximately 450 Palestinians who had been waiting to enter Gaza were finally supposed to be permitted entry. Days before, the announcement had been made that the Rafah Crossing between Egypt and Gaza would open to allow passage into and out of Gaza. Many of the Palestinians at al-Arish had been waiting since the beginning of June for the border to open. Others had been exiled for over a year, outside of Gaza when Egypt sealed the border shut following Hamas’ taking control of Gaza in June 2007.

Silenced and out of the international spotlight, the Palestinians waiting in al-Arish said that their plight at the closed crossing is either ignored or politicized. Many were running out of money, while others had completely run out, having waited for the opening of Rafah for weeks without earning an income. Approximately 200 of the Palestinians who waited to re-enter Gaza were in dire financial circumstances, many borrowing money, others begging, some sleeping in the streets.

Many came from countries where they hold work permits, taking vacation time to visit family not seen in years. “We risk losing our jobs and our residency permits,” explained Mahmoud, a 28-year-old truck driver now living in Sweden. “Otherwise, we must leave Egypt without having seen our families in Gaza,” he said. “We are now merely running on hope and faith that the border will open one day,” added 22-year-old Sameh (not his real name), from Gaza’s northern Jabaliya refugee camp and formerly a student at one of Cairo’s universities.

There appears to be little support from the Palestinian Authority and its diplomats in Cairo. Many Palestinians who arrive to al-Arish have no idea how they can enter Gaza, asking others in the same situation or even foreign journalists for advice and help. The lucky are directed to the PA representative in al-Arish, who adds their name and passport information to the long list of those waiting. Some, however, feel it makes little difference if their name is on the list.

Waiting

“I’ve been waiting for two months now,” said Sameh, the university student who hoped to continue his studies in Gaza. “I put my name on the list right away, but it didn’t achieve anything. We’ve been told repeatedly that the border will open soon, but weeks have passed and here we are still here, wasting our money. No one is looking out for us, not our own representatives, not the Egyptian authorities,” he added.

“I’ve been here since 23 July,” explained Muhammad, who left Gaza in 1996 to continue his university studies abroad. Recently his mother in Gaza became very ill but doctors were unable to diagnose her ailments. Worse, due to the deteriorated conditions in hospitals and clinics, the lack of medicines and equipment and sufficient staff, she is not a priority case. There are too many more critical patients, including those injured during Israel’s frequent pre-truce military operations in Gaza.

Stuck waiting in al-Arish, Muhammad feared his mother would die before he could see her and was frustrated at the game being played with their lives. “My family is the sacrifice of a political problem. We aren’t Fatah, Hamas, or any faction. My mother needs help for her condition, but can’t get it, and I need to be with her, but can’t get in,” he said.

Muhammad explained the process of trying to leave Egypt to Gaza: “I went to the Rafah crossing and was told by Egyptian authorities to go back, that the crossing was closed. I returned to al-Arish and gave a copy of my passport to the representative from the Palestinian embassy and was told I must wait. But I have no idea how long they will make me wait, nor how long I can wait. I have a wife and my studies back in Europe.”

Jaber was accepted to the Cairo University faculty of medicine in 2005. Since then, he has spent the last three summer vacations trying, and failing, to enter Gaza to see his family. He was not convinced he would succeed before the school year resumed. “I don’t think the border will open,” he said. “I think I’ll spend another year here without seeing my family. It’s very difficult staying here, waiting, hoping to see your family but realizing that you can’t.” He added that he is not alone in his separation from Gaza: “This isn’t just my story. I have maybe five other friends also studying at the faculty of medicine who want to go back to Gaza.”

When the rumors spread that the border would open, waiting Palestinians packed their bags and headed to the crossing. Most did so in vain, hoping they would be able to show their ID and cross into their homeland. However, the stranded inevitably ended up back at their al-Arish accommodations, waiting for the next rumor.

A handful of medical patients did pass through into Egypt, seeking treatment and then returning home. They held the coveted yellow cards, Egypt’s recognition of the ill or injured, the key to the closed border gates. Seven crossed back into Gaza one day, 15 another day, five the last time. But they were a scant fraction of those who needed to return home.

Raed, a 34-year-old Ukraine-trained doctor, and his Ukrainian wife considered trying to return to Gaza in January with their daughter and young baby when the Rafah border wall was torn down by Hamas in a temporary break of the siege. “I need to be near my family, my birthplace. My children need to see their grandparents,” Raed explained. He had unsuccessfully tried to enter Gaza a year before and ultimately returned to Ukraine to work. But in January, his newborn baby was too young, he felt, to travel and live in Gaza. He’d wait six months before trying to re-enter.

Entering Gaza became all the more urgent after Raed’s father was placed in an intensive care unit due to acute respiratory problems. The family joined the hundreds of others waiting in al-Arish hoping to bid loved ones in Gaza a last goodbye. Raed lost this chance Wednesday, when he learned of his father’s passing.

Policy of separation

“Fifty days. I’ve been waiting here for 50 days now,” explains Mahmoud, the truck driver living in Sweden. “I was due to start work two weeks ago, and I keep telling myself I’ll leave Egypt tomorrow. But then I hear that maybe the border will open. I can’t give up this option. I can’t give up my hope.”

Meanwhile, Sameh, the university student, spoke of separation, not only between Palestinians in and outside of Gaza, but of Gaza from the West Bank. Referring to the 19 June ceasefire between Israel and Palestinian armed resistance in Gaza, Sameh said: “By enforcing the truce only in Gaza, Israel is trying to enforce the idea of separating Gaza from the West Bank, as two separate states. But West Bank Palestinians are just like us, and we can’t ignore the oppression they in the West Bank face under occupation.”

On 30 August, just before Ramadan began, Egypt finally opened the Rafah crossing for two days, allowing in most of the Palestinians waiting in al-Arish at the time and letting hundreds of Palestinians and Egyptians inside Gaza exit to Egypt. However, this was a one-time measure and not a change in policy. With the Rafah crossing tightly re-sealed, the siege still firmly in place. The thousands of patients still needing medical care outside of Gaza, hundreds of students still cut off from their schools abroad, and the countless separated families continue to call for the border to open and remain open.

Eva Bartlett is a Canadian human rights advocate and freelancer who spent eight months in 2007 living in West Bank communities and four months in Cairo and at the Rafah crossing.

Related Links

- Political obfuscation and stranded Palestinians in Egypt, Serene Assir (1 August 2007)