The Electronic Intifada 16 May 2008

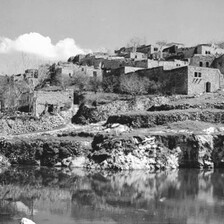

Stills from Shadow of Absence

“Born in Palestine. Died in Lebanon.” “Born in Palestine. Died in Syria.” “Born in Palestine. Died in Jordan.” The camera pans across an endless row of white tombstones. Shadow of Absence takes death as its subject yet in doing so presents a powerful statement about Palestinian life. Weaving elements of his own story of dislocation into the Palestinian collective narrative, filmmaker Nasri Hajjaj reverses the usual focus of Nakba documentary by exploring the denial of the Palestinian right to death in the homeland. Why can a Jew from any part of the world decree that their body be brought for burial in Israel while a Palestinian even a few kilometers away in the West Bank or Lebanon cannot choose eternal rest in the homeland?

Opening this tale which says as much about the bulldozing of Palestinian land and way of life as it does about the digging of graves and burial rights, Hajjaj shows us al-Naameh, the village from which his parents fled to Lebanon. Today a farmer’s field a few kilometers outside the Israeli border town of Kiryat Shimona, the wind blows through the long grass with hardly a stone visible to mark its passing.

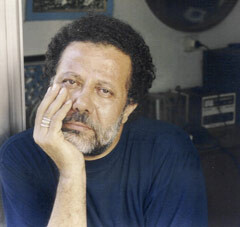

Director Nasri Hajjaj

Others get closer to home — but no more reach their destination than those buried in Hanoi or Paris. American citizen Edward Said could not be buried in his native Jerusalem and today rests in Lebanese soil. Ahmad Shuqairi, PLO chair before Yasser Arafat, requested to be buried in a cemetery as close to the border of the Jordan river as he could — lying eternally within sight of his home in Jericho.

On a visit to Ramallah at an early stage of the project the director says he was given encouragement to continue by Yasser Arafat. By the time it was finished Arafat too had become victim of the policy of preventing Palestinian burial — in his case at the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem. On the day of his funeral I awoke to see soldiers in the streets of my quiet East Jerusalem neighborhood. Crowds of people were walking towards Ramallah — the idea that they might return en masse with the body to the holy sanctuary was not something Israel could stomach.

Of course some Palestinians, through Israeli citizenship, Jerusalem ID or “luck” to die in Israel are able to be buried in the homeland. Writer and politician Emile Habibi, although having lived a life as an internal refugee in Nazareth, is today “forever in Haifa.” In 2001 crowds lined the streets of East Jerusalem as the body of Faisal Husseini was carried to the Haram al-Sharif to join that of his father Abdel Qader, immortalized in Palestinian national history for his heroic death defending the homeland in the 1948 battle of al-Qastel. Israeli security services attempted to prevent the burial of Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, American citizen and leading Palestinian intellectual, in his hometown of Jaffa, yet death in a Jerusalem hospital meant his family and friends could use Israeli law — for once — in their favor. The view of the lonely hill top Jaffa cemetery overlooking an endless sea is one of the most poignant and symbolic of loss in the film.

These families have a grave at which to mourn. Interspersed with the stories of individual struggles with authorities and bureaucracy the film recalls many thousands of Palestinians, fighters and civilians, for whom there is no known grave at which families can weep. Some must stand before a collective grave knowing that somewhere under the earth, along with hundreds of others killed in Tel al-Za’atar or Shatila or some other massacre, lies a murdered mother or son, husband or daughter. Some like Um Issam, Hajjaj’s family neighbor from Ein al-Hilweh, have no certainty of when, how or if, a loved one has died at all. I peered closer as I recognized a road bridge I have driven over many times, Jisr Banayt Yakub, linking the Galilee and the Golan Heights. A wave of nausea hit me as the camera panned closer behind the road to reveal one of the “Cemetery of Numbers.” There, until recently moved, lay an unknown number of Palestinians — and other nationalities — captured dead or alive and buried without notification of family, friends or international humanitarian organization.

My only minor criticism would perhaps be the reinforcement of the image of men as martyrs, women as those left behind to weep and mourn. The gendered nature of war and politics means that to a great extent this is true — but perhaps I would have liked to hear more about some of the famous women who died in exile or active resistance, as well as the many thousands of nameless women who died fetching water for their families, crushed by buildings shelled from the air or shot in the streets. Hajjaj mentions some of these women, but a greater examination would have perhaps added to this haunting picture.

Shadow of Absence is a vivid and painful portrayal of personal and collective dislocation. The poetry, music, images and semi-poetic prose make the documentary a work of art, a song to a distant homeland, mourned in death as well as life. The music of Gorecki’s “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” and the voice of Kamilya Jubran over the images of Um Issam, dusty white stones, sea and sky will remain long after the credits have closed.

Isabelle Humphries is completing doctoral research on internally displaced Palestinian refugees. She can be contacted at isabellebh2004 A T yahoo D O T co D O T uk.

Shadow of Absence screens tonight at the Houston Palestine Film Festival. for more information see: http://www.hpff.org/.

Related Links